The judging process for Architizer's 12th Annual A+Awards is now away. Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter to receive updates about Public Voting, and stay tuned for winners announcements later this spring.

To make an impact is not simply to have influence; by definition, the word implies forcible contact. There is a degree of strength built into the word. Architizer’s Impact in Design Award is a special honor that celebrates architects and designers using their skills and passions to address local and global crises in collaboration with communities — environmental, social, political or economic. Their work forms a catalyst for positive change, not only in terms of meeting the needs of their project’s occupants but also by creating spaces in which communities can adapt, grow, and reinvest in their livelihoods long-term. Impact in Design Award Honorees are not only leaders; they are forces of change — in the industry and society at large.

The project description for any of Mariam Issaoufou Architects’ (formerly atelier masōmī’) impressive body of work reads as the clear application of these principles. The Niger-based firm was a clear-cut choice for Architizer’s Impact in Design Award at the 11th Annual A+Awards gala in Paris. Founded in 2014 by the firms namesake, Mariam Issaoufou Architects is an architecture and research firm guided by the belief that architecture is an important tool for social change. They tackle public, cultural, residential, commercial and urban design projects throughout the African continent and beyond. In each of Mariam Issaoufou Architects’ projects, the firm emphasizes architecture’s potential to elevate, give dignity and better people’s quality of life.

This is seen in projects like Dandaji Market, which provides a home for a rural marketplace by referencing local adobe post and reed roof construction while pushing the typology forward and imbuing users with a sense of permanence and pride. Likewise, the Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center for Women and Development draws on Liberia’s architectural heritage — in particular, traditional palava huts, which are characterized by towering but functional pitched roofs, which help with the area’s heavy rainfalls and augment natural ventilation — resulting in a complex with low energy consumption and material waste while maximizing its local resonances. Such projects promote economic sustainability by championing local materials and manufacturers, as well as builders and craftswomen.

Mariam, who was unable to accept her award in person due to travel restrictions imposed under the recent coup in Niger, shared an arresting video where she reflected on the state of our collective futures at a moment of widespread mourning and devastation, and on the impact of work, the core of which she sees as her conviction that “sustainability is as much about preserving people’s cultural heritage as it is about the climate, and the two are actually intertwined.” In the following interview, Mariam shares more about her work — intellectual and built:

DANDAJI Market by Mariam Issaoufou Architects (formerly atelier masōmī), Dandadji, Niger

Tell us a little about your story — how did you get started? How did your firm grow?

From a young age, I always liked to draw. I knew somewhere in the back of my mind that I wanted to pursue a career that would merge my love of drawing with my creativity. But architecture was a word that was alien to me. My childhood was spent living in a small town in the middle of the Sahara desert where I was surrounded by traditional architecture that dates back centuries.

For that reason, I never really understood the idea that architecture could only look one way to be valid and accepted. If the Western World that had colonized us could have a traditional architecture they have found a modern expression for, so could we. There was something incomprehensible — and frankly demeaning — to me about being asked to mimic others’ modernity and transpose it as the only legitimate way of living in the now. When I finally became an architect, my interest was naturally in making architecture that responds to its local context by addressing the social, ecological and economic challenges that reveal themselves in the process.

Niamey 2000 Housing by Mariam Issaoufou Architects (formerly atelier masōmī), Niamey, Niger

Looking back, which of your projects do you feel was the most significant to the firm’s development and why? [You can pick more than one!]

What a tough question! Looking back, I think each and every single one of my projects has contributed to our development as a firm and me as an architect. The design of our projects is always influenced by the context, climate and the people for whom we are building. For example, our housing developments in Niger (Niamey 2000) and Sharjah (Hayyan), are responding to different needs from our clients. But because they are both for people with a similar climate and religious background, we were able to build on the lessons we learned working in Niger in order to design the housing development in Sharjah.

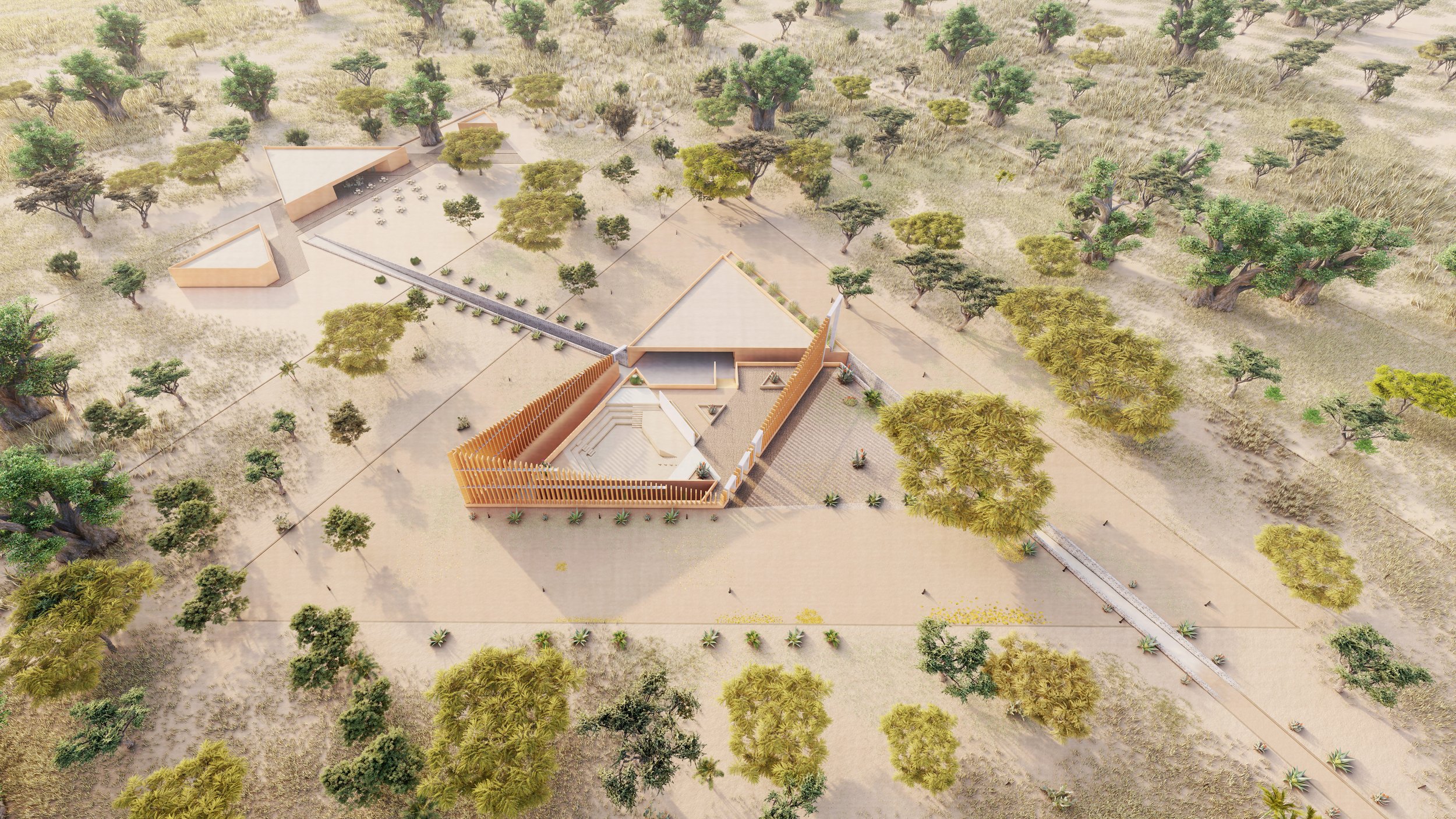

Bët-bi Museum by Mariam Issaoufou Architects (formerly atelier masōmī), Senegal

You have significant projects in development in Niger, Senegal, Liberia and beyond. In what ways does the cultural and environmental context of these locations influence your work?

Our projects respond directly to the climate, context and cultures of the places in which we work. Before I can even pick up a pencil to start designing, we go through an intensive research phase where we uncover clues about the people who inhabit the places (both historically and in the contemporary sense), we look into the climate and architectural histories of each place in order to produce designs that are relevant.

In Liberia, for example, The Ellen Johnson Sirleaf Presidential Center’s design is inspired by the traditional Palava huts of the country as well as Madame Ellen Johnson Sirleaf herself, Africa’s first woman president and someone who continues to fight for gender equality. The same goes for Bët-bi Museum in Senegal, which is designed to form part of the landscape, making it a welcoming space for everyone, a public space, before a museum. The galleries are sunk below the ground, as a nod to the sacrality of the land, honoring the Serer and Mandinka people, while also creating a space for art and creative expression.

Mariam Kamara accepting the Impact in Design award on behalf of her firm at the 11th Annual A+Awards | Photo by Alex Bonnemaison

What does winning Architizer’s Impact in Design Award mean to you and the firm?

We are deeply honored to receive the Impact Award. Mariam Issaoufou Architects (formerly atelier masōmī) will have been around for a decade in 2024. Operating an architecture firm is not easy, particularly working from our context. It is quite energizing, particularly during challenging times, to be recognized for the work that we do.

If you had one piece of advice to offer the next generation of architects across Africa, what would it be?

It is up to us to imagine what our future looks like. We have to reclaim agency over our lands and our identities. Don’t be afraid, don’t apologize, we need more of you.

Top image: Hikma Community Complex by atelier masōmī, Dandadji, Niger

The judging process for Architizer's 12th Annual A+Awards is now away. Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter to receive updates about Public Voting, and stay tuned for winners announcements later this spring.