Wandile Mthiyane is an Obama Leader, TedxFellow, architectural designer, social entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Ubuntu Design Group (UDG) and The Anti-Racist Hotdog. He is proud to introduce The Tea, a peer-to-peer inclusion rating platform.

For far too long, companies have chosen to remedy discrimination after the fact rather than proactively cultivating prevention tactics to ensure employees don’t endure negative and potentially traumatic experiences. This reactive default means that the people who plan our homes, neighborhoods and cities don’t have a plan preventing them from facing harmful and dangerous workplace situations. It’s too easy to simply blame architecture culture; architects shouldn’t have to depend on Plan B–lawsuits, support groups or even have therapists on speed dial. What if you had all the information you needed on a company’s culture before applying?

Recently, I asked some friends what they wished they had known before entering the workforce, and their responses shed light on the challenges they faced. Each told me a harrowing story about intersectional discrimination in the workplace: significant pay gaps, inadequate maternity leave and administrative reluctance to address these issues and others. Comparing their stories exposes how similar problems can be found anywhere in the world, with women and people of color trying to combat workplace discrimination while simply trying to do the jobs they were hired for.

One experience was shared by a Black female friend who worked as an architectural designer in South Africa. After her first year, the company hired her white male classmate from university, assigning her the task of mentoring him for six months and teaching him about the firm’s design philosophy. One day over lunch, he unexpectedly expressed his dissatisfaction with his salary and, in the process, revealed the significant pay gap between them. Surprised by this revelation, my friend confronted her boss, and the conversation that followed is almost unbelievable.

Library in Anzin by Dominique Coulon & Associés, Anzin, France

The boss initially justified the disparity by explaining that her classmate had financial responsibilities, such as paying rent to his mother. She pointed out that she paid rent to an actual landlord. The boss mentioned that his colleague — again, who she was mentoring — had a car, so they need to uphold his living standard, to which she responded she’d also have a car if she were compensated fairly. Only when she threatened to quit did she gain a raise to match her classmate’s salary.

These problems persist in North America, too. My Asian friend from Canada shared a comparable account of discovering that she was being paid significantly less than her colleagues. When she confronted her boss about the inequity, her boss quickly deflected the issue to the HR department, adopting a stance of concern and promising action. A week later, the boss informed her that the matter had been resolved and presented her with a list of goals she needed to achieve within a specific timeframe to earn a raise. Frustrated, she questioned the idea of needing to prove herself for a job she was already overqualified for just to receive equal pay. In the face of her threat to resign, the matter was resolved within a week.

Meanwhile, one of my white female friends in Germany revealed an age-based layer to gender discrimination. As she approached her mid-20s, she encountered difficulties securing a job. Once gainfully employed, she faced even greater hurdles in obtaining promotions. Companies perceived her as a potential liability because she could get pregnant, thus hindering her progress at work. Almost ironically, policies favoring maternity leave have led male bosses to view women as liabilities.

Clearly this problem is pervasive worldwide and is linked to problematic workplace cultures. While relevant in most workplaces, architecture is an industry well known for its toxic work culture. Architects have to deal with unnecessary competition between colleagues, work long hours, and pay off a mountain of school debt in the meantime. In 2023, Architecture Journal reported that over 40% of architects work at least 10 hours of overtime per week, largely unpaid, according to an AJ study completed by 400 architects. This work-pace leads to high burn-out rates, with almost 97% of architects reporting burn-out.

Take into consideration women and People of Color have to fight their own struggles against workplace discrimination while doing their own work in these already-toxic spaces. According to the National Council of Architectural Registration Boards (NCARB), out of the 121,603 licensed architects in the U.S. as of 2022, only 2% (2,492) are Black. Among them, only 566 are Black women, despite Black people making up 12.6% of the country’s population, with 52% of the Black population being Black women. These statistics clearly highlight the significant underrepresentation of people of color, particularly Black individuals and women, exposing them to vulnerability in white male-dominated studio spaces. Moreover, disparities in power structures within firms further exacerbate the situation, as women face additional challenges and are less likely to complete licensure, impeding their progression to principal roles. As one of my American friends noted, employees should have the ability to go to work and focus solely on their tasks without the added burden of being the unofficial and unpaid advocates for DEI within their companies.

Clearly, DEI programming is not enough to change our workplaces. Over the past two years, my team and I have partnered with leading social psychologists from Harvard, Columbia, Deloitte, and The Resolution Project, and closely studied company culture while consulting with architecture firms, both large and small. Throughout our research, we engaged with young professionals to understand what they wish they had known before entering the workforce, particularly what would have helped them make better decisions about the places where they would spend the majority of their adult lives.

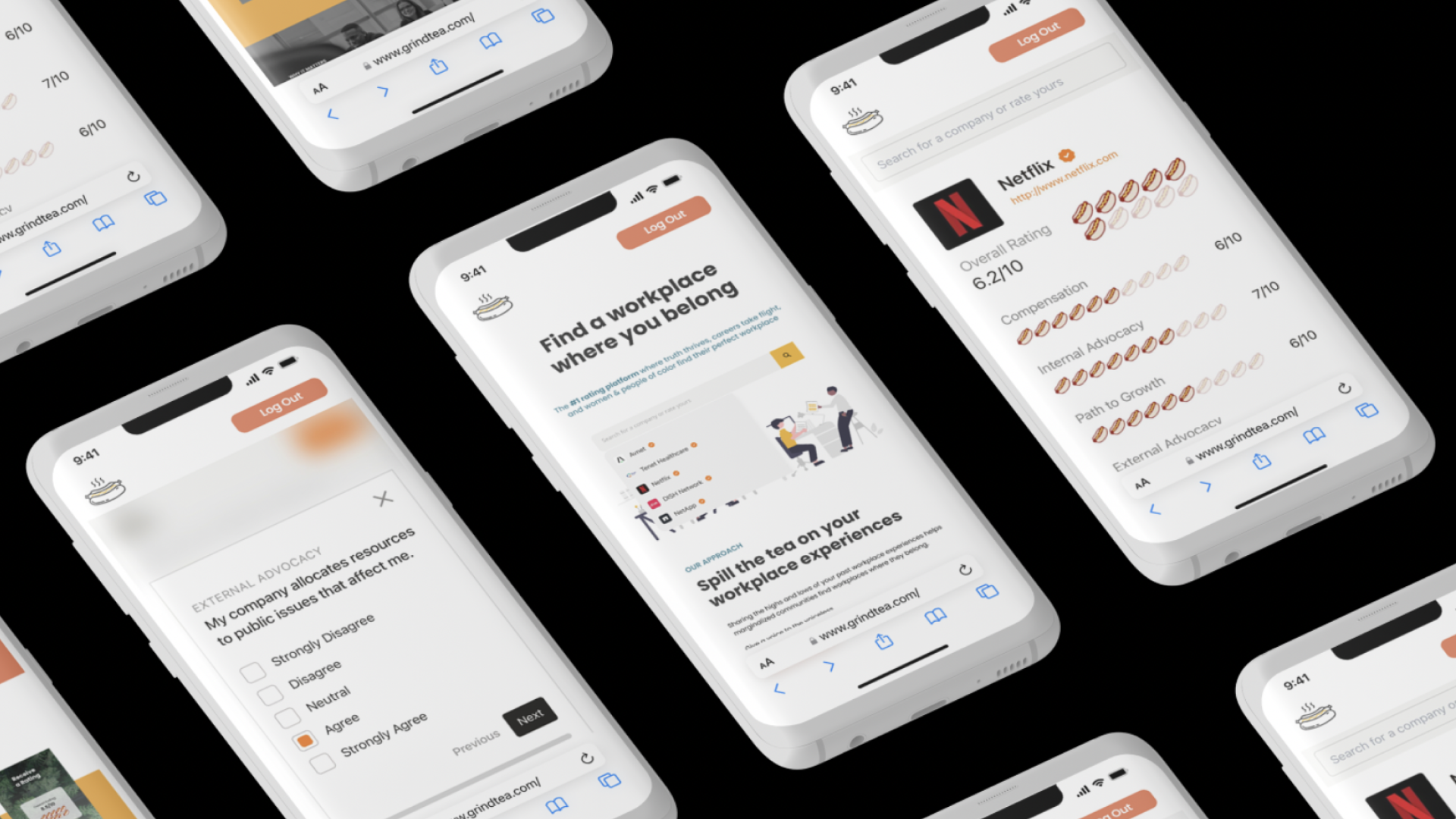

Building upon this work, we developed The Tea: a demographic-specific, peer-to-peer inclusion rating platform that connects women and people of color to workplaces where they are truly valued. The Tea uses key workplace indicators that matter the most to individuals of similar demographics, based on research that shows why women and people of color leave or stay in workplaces. The platform uses ratings based on key workplace indicators such as salaries and benefits, path to growth, internal advocacy, external advocacy, authentic self, and valued expression. Users can also filter based on race, gender, sexual orientation and age to find how people that look like you have experienced a particular workplace.

The Tea is also built for firm leaders and HR directors, helping them know exactly what they need to improve in their own workplaces and the steps they have to take. Instead of providing negative anecdotes without clear solutions, The Tea’s data-driven key indicators show more precisely where companies need to improve. Companies can even upload their own efforts to address each indicator, so applicants can see how a company is dealing with certain problems. Above all, we value everyone’s identity and security, online and in the workplace: just log in with your LinkedIn, and your reporting remains anonymous.

In the end, The Tea benefits everyone involved. It provides employees with a safe space to identify companies that truly value their labor, eliminating the need for them to be BIM managers and the office’s designated MLK just because they’re a person of color. Simultaneously, employers gain valuable insights on how to create the most culturally diverse and inclusive firms in the world. We are transforming DEI from a mere aspiration into a tangible reality. Let’s join forces and spill the tea together, ensuring we never have to face these challenges again!

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.