Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

In the immediate aftermath of the tragedy of 9/11, which took 3,000 lives, as others speculated about the designs and symbolism of building on Ground Zero, the New York Times’s David Dunlap took stock of the city’s existing towers. “Even now, a skyline of twins,” he said, “New York, New York has a penchant for saying things twice.”

From the duo towers of luxury apartments along Central Park West to the gateway created by the Schomburg Plaza in Harlem to the AOL Time Warner Center at Columbus Circle, under construction at the time of the terror attacks, along with an abundance of church spires and even minarets, the writer made a compelling argument for the endurance of a particular trait on the Manhattan skyline: the “Synergy of Twos.” However, in the competition to design the new site, few designers made an ode to such dynamic duos (Norman Foster’s “Kissing Towers” stands out in this regard).

Anthony Quintano, September 11th Tribute in Light from Bayonne, New Jersey, CC BY 2.0

From today’s perspective, perhaps the absence of twins in the competition was a portent of things to come. Twenty-one years later, New York’s skyline has has dramatically transformed. Studded with showcase pieces by global firms and name-brand architects — each with its signature style of glass tower for a global city rather than a particular place — many of the standout buildings that have been erected in the past two decades are tall, solitary structures. The ghostly tribute to Minoru Yamasaki’s Twin Towers that beams out of lower Manhattan each anniversary is one of the few notable post-attack twins to mark the skyline.

Yet, while many of these new towers are testaments to the new era defined by mega-development, they are also more subtle testaments to the legacy of the conspicuously absent towers. Since 9/11, innovations in design and building technologies have re-made what is possible in the realm of skyscraper design, but precedents set by Yamasaki in the original 1960s design paved the way for the today’s skyline.

Ambitious Design

In 1962, Yamasaki, who had designed just two other skyscrapers, was commissioned by the Port Authority of New York to design the World Trade Center. A devotee of Mies, his idealist design expressed its humanism through technological progress. His task distinctly combined elements of engineering, design and planning. (It should be noted that his original plan was substantially altered through the development process.)

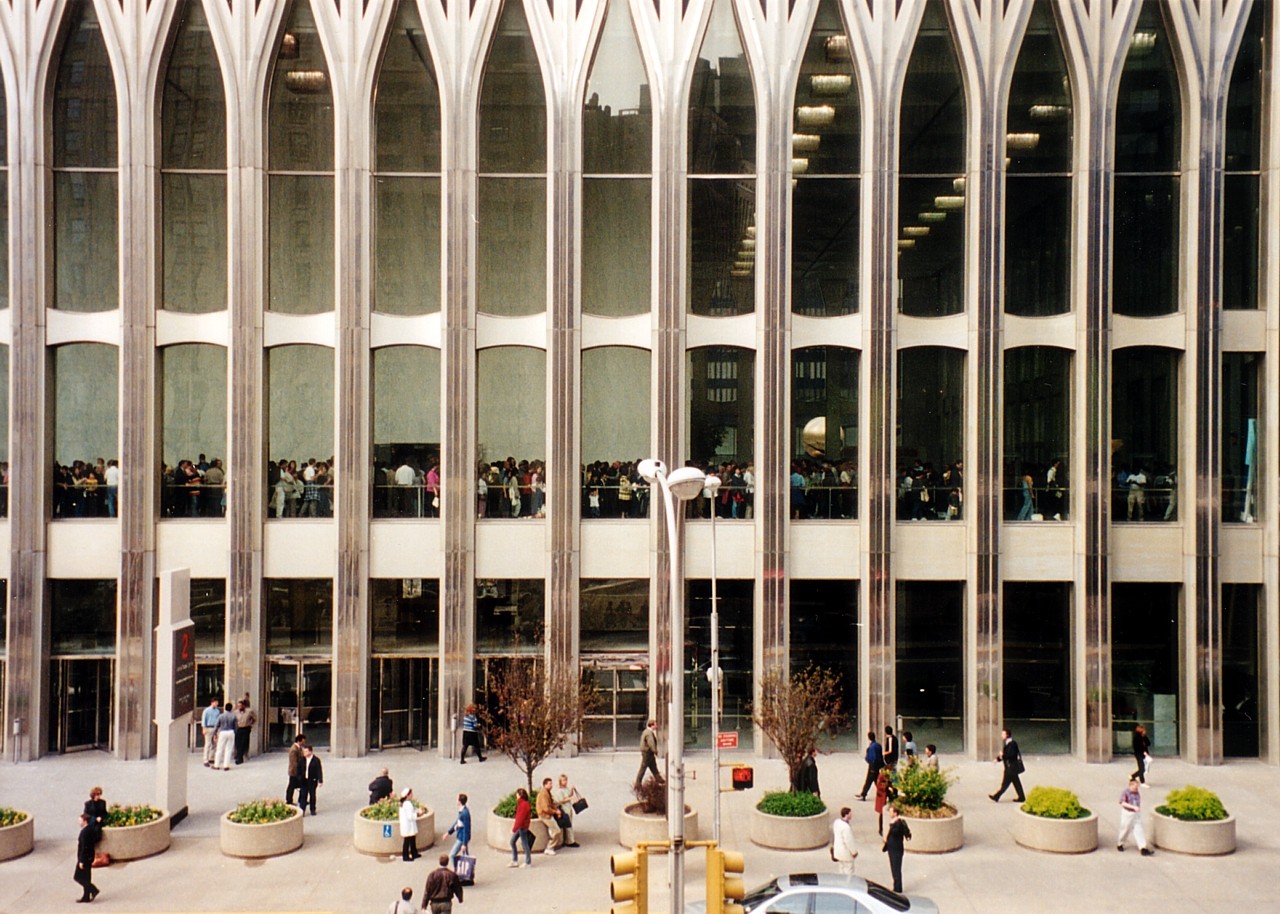

Despite their elegant detailing, including the narrow, gothic-inspired office windows expressed in the building façades in aluminum-alloy cladding, the sheer ambition in size towered at an entirely different scale than the rest of Manhattan. While they were originally planned to top out at a proposed 80 floors, in the end the towers totaled 110. Soaring to 1,368 and 1,362 feet tall, the towers overtook the Empire State Building to become the world’s tallest buildings when completed in the early 1970s.

The Twin Towers were technological marvels that, despite public misgivings about the aesthetic and urban qualities, illustrated the potential of framed-tube construction. By shifting much of the load to the stiff tubes of heavy steel on the exterior walls, the design opened the office floor plans. Minimal columns were needed inside. Meanwhile, the steel x-bracing and sheetrock at the twins’ core allowed the buildings to sway in the wind. When it came to elevators, Yamasaki and his engineers also innovated by creating a novel sky-lobby system where larger elevators fed into a system of smaller floor-specific elevators.

For contemporary critics such as the New York Time’s Ada Louise Huxtable, the disjuncture between the scale of the structure and the delicacy of their façades posed a problem of structural expression. By contrast, with his design, Yamasaki hoped that “The day of the all-glass building [would be] finished,” adding, “As for mirror glass, I detest it.”

Battery Park City and the former Twin Towers at the World Trade Center NYC via the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division and Wikicommons

Material Lessons

While these audacious engineering feats paved the way for skyscrapers in the late 20th century, they also contributed to the tragedy in the new Millenium. Like most buildings before 9/11, Yamasaki’s towers were designed to withstand total collapse. However, when exposed to the high temperatures, the steel columns in both structures weakened. The loads they had once born were redistributed to other structural supports unprepared for the extra burden.

Since 2001, progressive collapse and redundancy have become central considerations in the engineering of skyscrapers. Buildings are now designed and built with multiple reinforcements to ensure that if one of the critical beams or columns in a design is compromised, it won’t lead to the total collapse of the entire structure.

Materials have also been re-thought. For example, unlike steel, concrete does not substantially change physically or chemically when subjected to such temperatures. However, in place of traditional reinforced concrete, the material’s mechanical properties are enhanced by mixing high-strength needle-like steel microfibers into the mixture, which further strengthens the material from cracking or spalling.

One World Trade Center by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), New York City, New York | Photo by James Ewing

Immaterial Changes

The material lessons that came in the wake of the attacks are paralleled by the immaterial changes that the city has undergone. Skyscrapers posed more than a technical quandary; their symbolic role in the city’s skyline since 9/11 has perhaps been even more consequential.

While the idea of building back at first seemed anathema to many, the gaping hole left in the skyline by Yamasaki’s absent towers proved urgent. Again, the need for height became apparent in December 2003, when the design for the new center was revealed. And, like the towers that previously stood on the site when the new One World Trade Center was finally completed in 2014, it set a record height at a symbolic 1,776 feet (without the spire, the roof is 1,368 feet tall). But, as with Yamasaki’s buildings, the expression of its engineering and technical prowess took precedence over its more immediate aesthetic impact.

“One World Trade implies (wrongly) a metropolis bereft of fresh ideas,” Michael Kimmelman reviewed, “It looks as if it could be anywhere, which New York isn’t.” Aside from its height, the towering glass structure has few distinguishing characteristics, shared with the swath of supertalls — towers that rise above 1,250 feet — that have cropped up throughout the city in the same period.

Though rare in the 20th century (before the Twin Towers, just the Empire State, Chicago’s Sears Tower boasted this title), today, a survey by the Skyscraper Museum lists 58 buildings worldwide that will stand by 2024 — seven of which are in New York City. From Rafael Viñoly’s 88-story supertall at 432 Park Avenue to Jean Nouvel’s 77-story residential tower 53W53 (also known as the MoMa Tower), the soaring height speaks louder than aesthetic or humanistic detailing in most of these buildings.

Yet, in response to the monotony of towering glass in millionaire row, the skyline has had several notable contributions that are a bit more unique. From the undulating profile of Gehry’s 8 Spruce Street (which went up in 2008) to the Jenga-like stacks of Herzog & de Meuron’s 56 Leonard Street (first revealed in 2007, completed in 2017), to Bjark Ingels the tetrahedral apartment building, or “court scraper,” VIA 57 West, (2016), the list of quirky scrapers attempting to shake up this trend goes on and on. In a sense, they are reacting to the precedents set by Yamasaki in their own way.

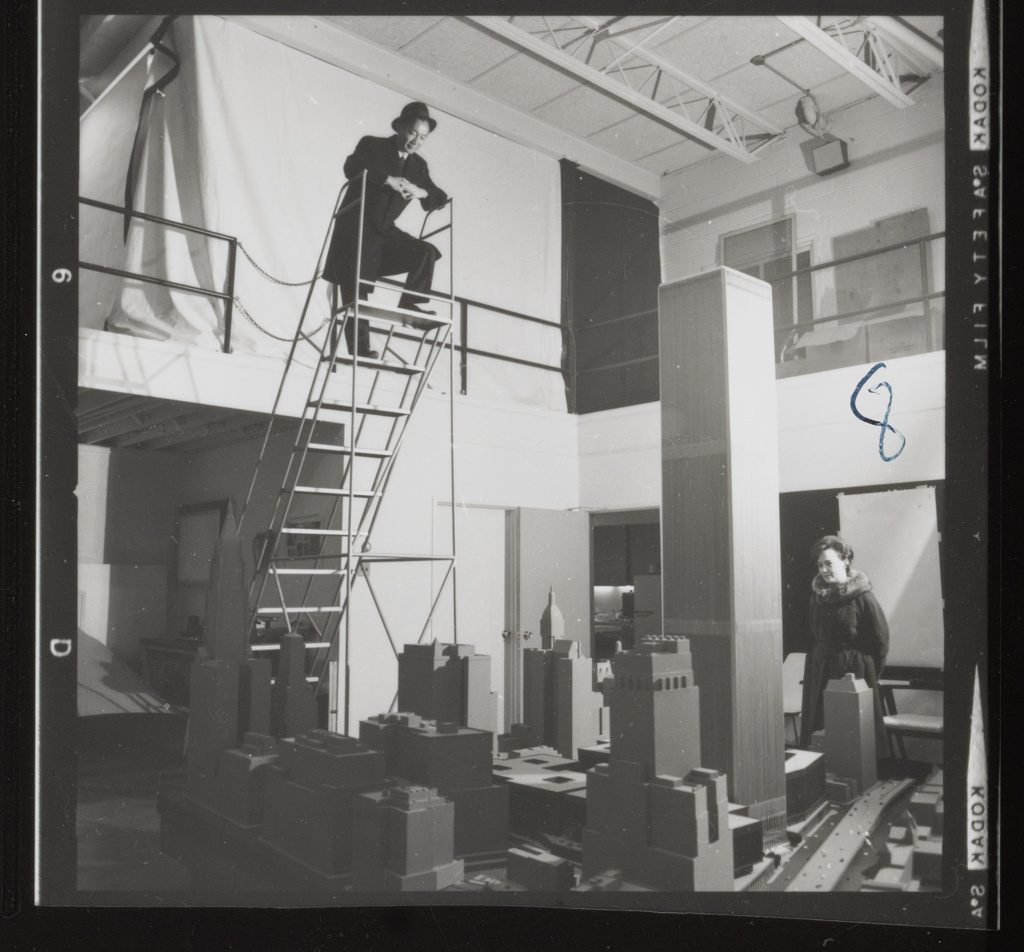

Architect Minoru Yamasaki on a ladder looking down at a model of the World Trade Center, Photo by Balthazar Korab Studios via Library of Congress

As Adjaye Associate’s 130 William nears completion, the façade’s richly textured precast concrete panels make a similar statement to Yamasaki’s gothic-windows: let’s bring down the curtain on the glass building era. The distinctive silhouette of the 66-story luxury condo building celebrates the ziggurats and masonry construction typically found its lower Manhattan context.

Perhaps it is no longer true that we can call New York, New York a city of twins; however, the legacy of Yamasaki’s two towers has symbolically and practically given shape to the skyline as we know it today. Instead of focusing on lessons learned in the immediate aftermath of a tragedy, going back to 1970 and considering the engineering acumen and design audacity that Yamasaki’s towers demonstrated is their true legacy.

From the extensive research into structure, materials and services enumerated above, to the wind tunnel studies and “viscoelastic dampers” that enabled them the twins to sway in the wind, imperceptible to the naked eye, to massive statement that their outsized scale made on New York’s skyline, already in 1970 Yamasaki had begun paving the way for the city as we know it today.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

One World Trade Center

One World Trade Center