This interview was conducted by Vincent Martinez. Architecture 2030’s mission is to rapidly transform the built environment from a major emitter of greenhouse gases to a central source of solutions to the climate crisis. For 20 years, the nonprofit has provided leadership and designed actions toward this shift and a healthy future for all.

The office of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill has long studied issues of density, asking questions about how we might — and if we should — build at various scales, including the carbon impact of these choices. Those explorations resulted in a research project and book, Residensity : A Carbon Analysis of Residential Typologies (Oro Editions, 2022), and the firm has continued to address these questions. I talked with Gordon Gill, Christopher Drew, and Robert Forest of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture (AS+GG) about why it is important to look at planning and density as we think about carbon… and how rapidly developing regions can best integrate infrastructure and buildings.

ResiDensity book cover, Photo by Andrew Griffiths from Lensaloft Aerial Photography

Vincent Martinez (VM): Since 2020, we have been encouraging a shift to broader thinking about carbon, from operating emissions of energy consumption to embodied emissions of materials and from building design to urban planning. Indeed, you spoke on stage at the CarbonPositive event in March 2020 in Los Angeles about Residensity and what your teams were learning about planning for residential dwellings and how density and carbon relate. Can you share with us some of this thinking? What more have you explored since Residensity? How is your team exploring density intelligence today?

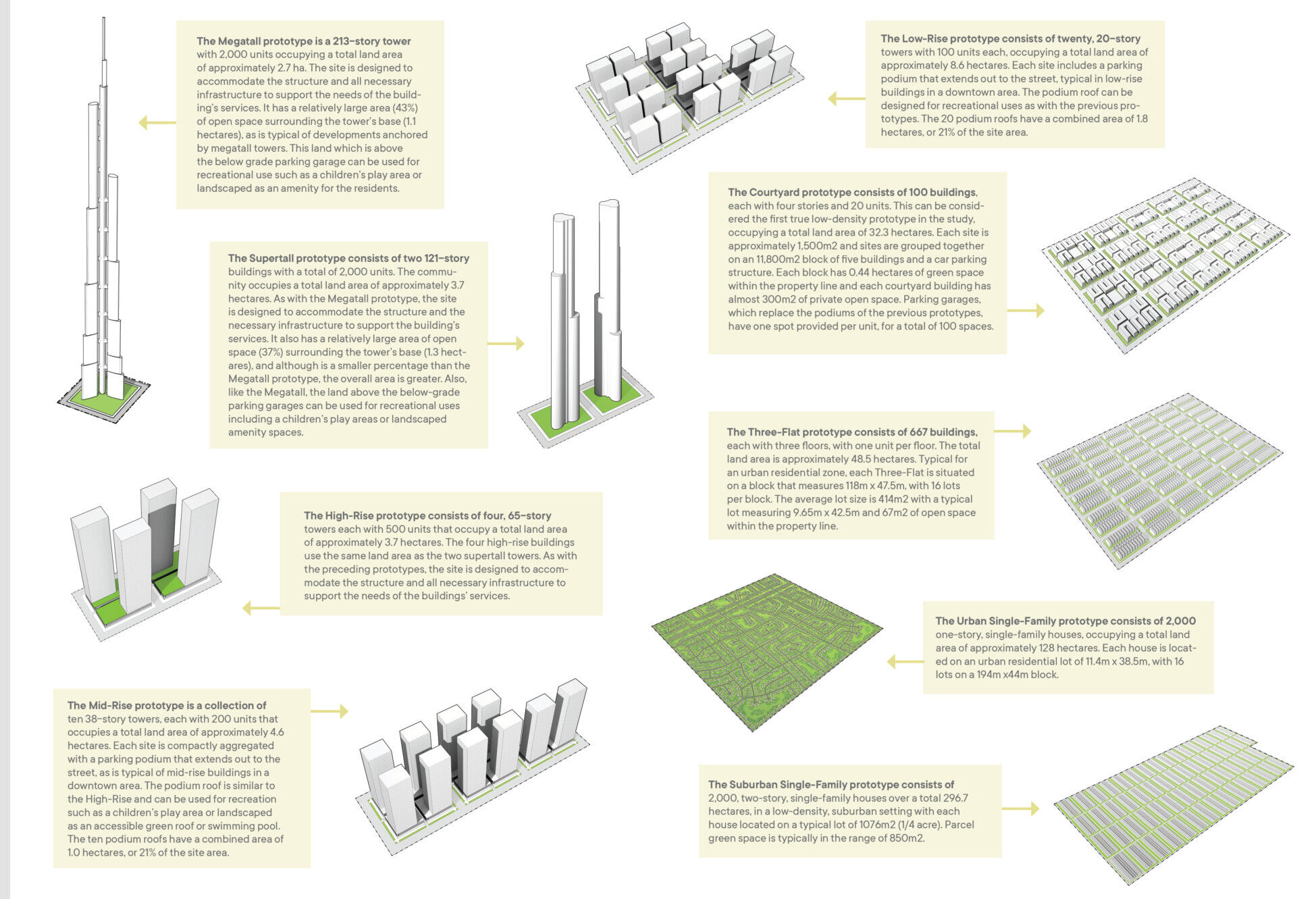

Robert Forest (RF): Our initial goal with the Residensity research was to objectively look at density and how it can influence our design approach. Density is good from a carbon standpoint and from an urban human connectivity standpoint. The key is to design for a kind of density that benefits the community by enhancing the environmental performance of the buildings, spaces or parks. The research helped us approach our projects from master planning to the building scale, and then to a residential unit-specific scale.

We are now pushing a more detailed look into building materials themselves, their carbon content, how we use them more efficiently, and how we can influence the supply chain to drive lower carbon content material. As architects and designers, we have tremendous power to influence the construction industry and must do it. We are also now creating project dashboards to help our clients understand their carbon footprint and how day-to-day operational decisions can influence it.

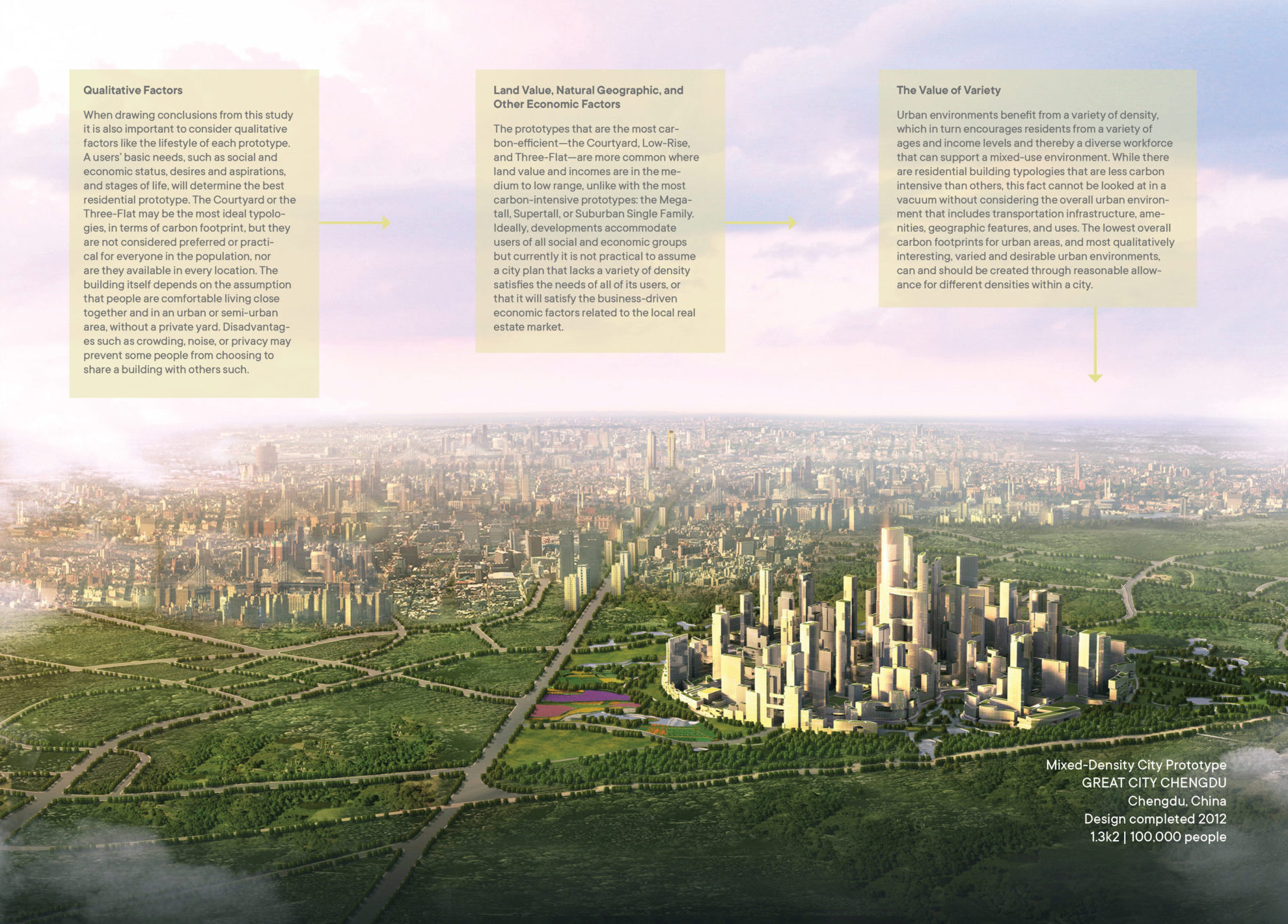

Gordon Gill (GG): As it relates to density and carbon efficiencies, we learned very early on that the effectiveness of the infrastructure is optimized through density. Specifically, mixed-use density in cities is best for a host of reasons, including energy efficiency, the opportunities for shifting loads and reducing peak loads, as well as simply a better lifestyle for inhabitants. The live/work equation is most efficient when integrated within a full spectrum of urban systems. Through the data collection and scenario testing of carbon-based planning, we can now plan ahead for more efficient infrastructure platforms with buildings as contributors to that infrastructure. This opens the door to revising economic equations for real estate and investment strategies.

Christopher Drew (CD): The Residensity study highlighted numerous densification outcomes, many of which, if factored into design or planning decisions, would provide low-carbon, environmentally responsible solutions.

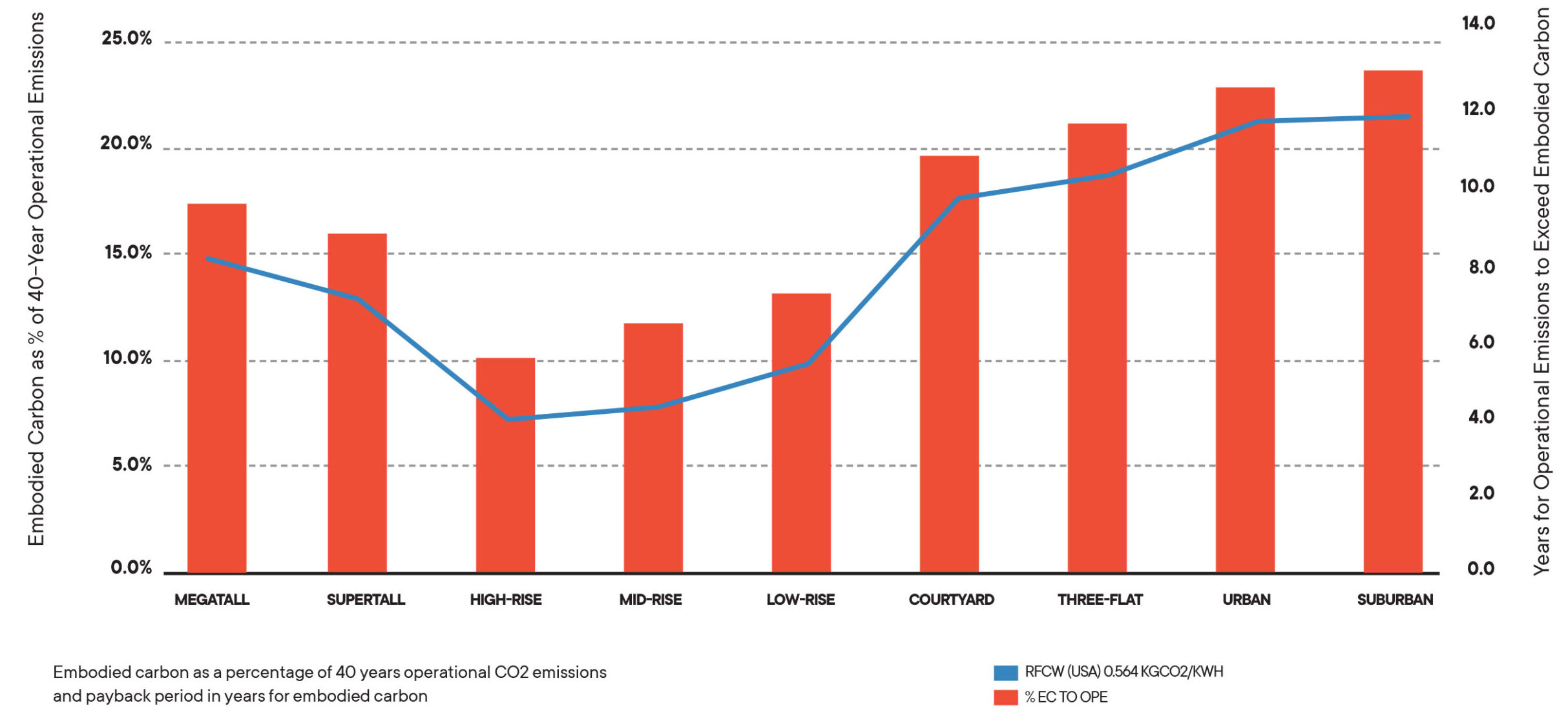

Through this effort, we investigated the relationship between operational carbon emissions and embodied carbon. Because we wanted the study to be relevant to a global readership, we considered various grid carbon intensities. We were particularly interested in the time taken for cumulative operational carbon emissions to exceed embodied carbon. In a typical building in Chicago, this number ranged from seven years for high-rise buildings to twelve years for suburban single family homes. But as we improve the thermal envelope of the building and move towards all-electric systems supplied by an increasingly decarbonized electric grid, that “years to exceed” value quickly starts to approach the turn of the next century. This should inspire a big shift in design thinking. We use sophisticated simulation tools to ensure that our designs balance embodied and operational carbon. If this balance is not properly considered, we could end up with a situation where net zero energy buildings have a higher lifecycle carbon footprint than code compliant ones.

Embodied carbon as a percentage of 40 years operational CO2 emissions and payback period in years for embodied carbon, Image courtesy of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture

VM: On the topic of infrastructure, the UN Environment projects that 75% of the global infrastructure in 2050 is still yet to be built. How much of this infrastructure need do you think could be integrated with our buildings or accommodated by our existing infrastructure?

RF: The key is to not look at buildings and infrastructure separately; they should be conceived as integral. In fact, designing buildings as their own power plants or water reservoirs reduces the amount of infrastructure that needs to be built. Infrastructure is typically being sized and planned long before specific building designs are done, which encourages infrastructure planners to rely on precedent more than tailoring to unique low-carbon conditions. At AS+GG we believe that Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) need to be set out for development with carbon as a key metric that guides efficiency to the infrastructure and the buildings as key integral parts of each other.

CD: Integrating buildings and infrastructure is long overdue. Although the energy use intensity of buildings has decreased thanks to initiatives such as Architecture 2030’s, the rising demand for electricity for data centers, transportation, industrial and residential electrification (the transition from gas heating to electric heating) —all while trying to meet carbon targets — is a major challenge. As we’ve seen many times in the past, we are addressing that problem while potentially causing a different problem. Many of the tech and parcel fulfillment giants are net energy positive. But if you look at the roofs on their warehouses and data centers, many ideally suited for photovoltaics, you’ll see few solar panels. The reason given is that the roofs are not built to support the weight of such panels. Sadly, today it is far cheaper to build a large solar farm on agricultural land than it is to build several smaller PV installations on warehouse roofs.

With 34 million Americans living in food insecure households, according to the USDA, it seems irresponsible that we don’t have code requirements to engineer warehouse roofs and others to support some PV coverage. The US currently hosts more than ten billion square feet of warehouse roofs. Imagine if just 60% of that was solar panels. That’s some 200GW of installed capacity, enough to produce almost 285 million MWh of clean electricity; enough to meet approximately 7% of the nation’s electricity needs, more if you factor in reduced grid transmission losses. We should be looking at ways to have infrastructure and open space, wilderness and farmland. As Bob notes, the key is to not consider buildings and infrastructure as separate layers — they must be integrated.

Excerpt from RESIDENSITY | Image courtesy of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture

VM: You’ve helped us to understand the embodied carbon emissions associated with infrastructure at different densities. What about transportation emissions that result from our land use planning? This seems to be one of the main climate impacts that urban planners focus on when they talk about land use and development patterns. As I understand it, this is mainly a function of building use. How is your firm considering this important variable?

RF: This is a great point and transportation is a main issue that we consider when planning our projects. Society has moved to an online economy, which would seem to lower traffic needs for people to drive to the store, but it has actually increased local truck delivery that many older communities or buildings were not set up to handle. How many delivery trucks do we see pulled on the side of road blocking traffic while deliveries are made? Many neighborhoods and communities are dealing with this. It’s time to think about the next level of delivery. How does drone delivery change the way we plan buildings and how do we allow for flexibility? Do building roofs become loading bays?

CD: And it’s not just on-demand goods deliveries. We talk about walkability almost as if there are only two modes of transport — walking and driving. However, there are many mobility and micro-mobility solutions vying for space on roads or sidewalks. How will all these play with autonomous vehicles and aerial vehicles and drones which will be busy delivering parcels, ferrying people, carrying out building cleaning and maintenance operations etc.? The future of transport is exciting and scary at the same time. How do you plan a three-dimensional road network? How do we provide power for a fully, or mostly, probably, electric transportation ecosystem?

Excerpt from RESIDENSITY | Image courtesy of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture

Vincent Martinez is President and COO of Architecture 2030, through which he works to solve the climate crisis by catalyzing global building decarbonization efforts through the development and activation of robust networks focused on private sector commitments, education, training and public policies.

Gordon Gill, FAIA, is a founding partner of award-winning Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture (AS+GG), Gordon’s work includes the design of the world’s first net zero-energy skyscraper, Pearl River Tower(designed at SOM Chicago); the world’s first large-scale positive energy building, Masdar Headquarters; the next world’s tallest tower, Jeddah Tower; and most recently Al Wasl Plaza, the open space for the centerpiece of Expo 2020 Dubai.

Dr. Christopher Drew, PhD. is the Director of Sustainability at AS+GG and brings an understanding of the relationships of the built environment with the natural environment and urban ecosystems through 30 years of experience, working as an ecologist, environmental scientist and sustainability manager.

Robert Forest, FAIA, is a co-founder of Adrian Smith + Gordon Gill Architecture, where he brings extensive knowledge of the execution of projects on an international scale. His expertise in both project management and technical architecture contribute to his comprehensive understanding of both the built environment and the practice of architecture.