The Art of Rendering: How to Place People in Architectural Visualizations

Humans fundamentally drive the narrative in architectural visualizations.

Humans fundamentally drive the narrative in architectural visualizations.

The proposals showcase alternate realities in which mankind’s major social and environmental issues shape the architectural landscape.

There was a time when no self-respecting rendering would allow itself to be seen in public without a zeppelin hovering somewhere in its desaturated sky.

The workflow that Alex Hogrefe uses to recreate drawings follows a similar procedure as that of actu ally hand-rendering an image.

“Architects should sketch. I am convinced of this,” says Bob Borson of MMB Architects. “I haven’t ev er — I mean EVER — personally met an architect who I thought was a good designer who didn’t sketch.”

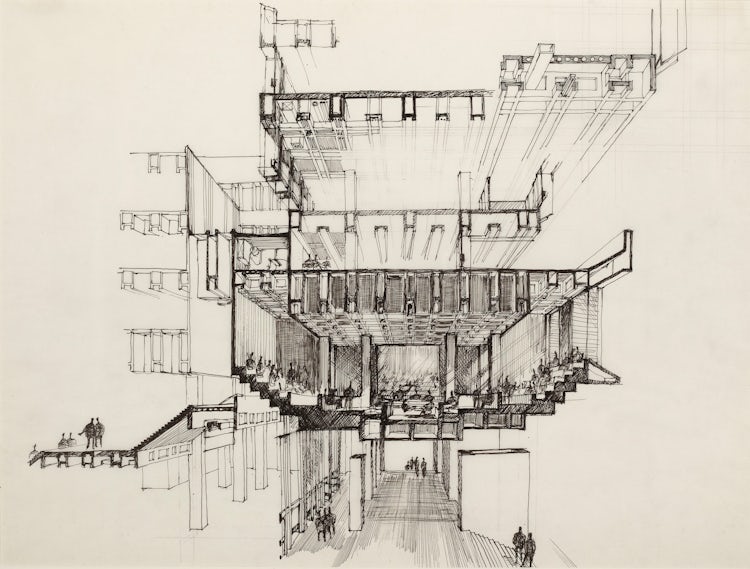

Rendering artist Rafal Barnas approaches each project individually.

In 1962, Boston was in trouble. Residents, manufacturers, and businesses were fleeing the city, leav ing behind acres of empty lots and boarded-up buildings. Residents needed a “new Boston,” and that year the city launched a rare open design competition in search of a new city hall that would symbolize—and help achieve—this rebirth. The two-stage, anonymous competition drew 256 entries, but in the end, the jury unanimously chose a bold, cutting-edge, and controversial design that was the work of “three young architects, two of them foreigners.” This concrete, Brutalist structure would become, David Dillon wrote, “one of the most remarkable debuts in American architectural history” and “arguably the great building of twentieth-century Boston,” according to Douglass Shand-Tucci’s definitive history, Built in Boston.

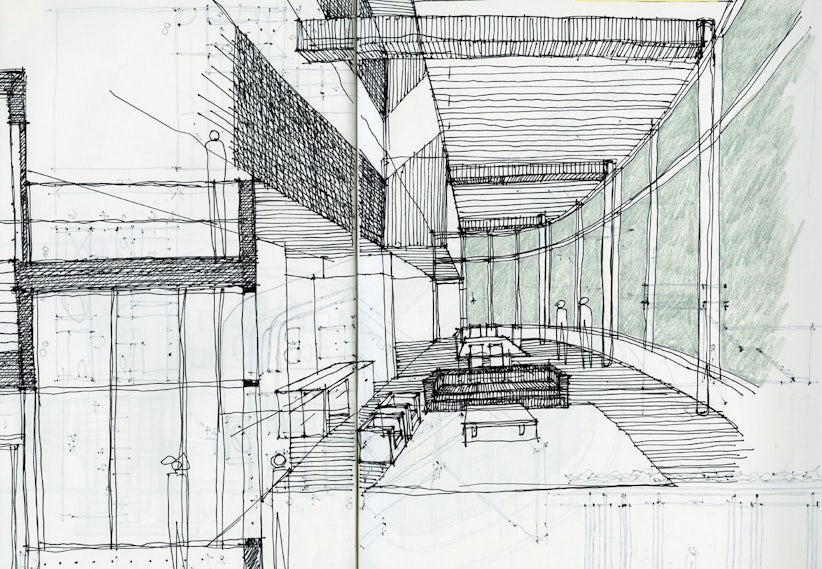

Using only a Micron fine-tip pen, Mazer creates stunningly detailed compositions with convincing dep th.

Allied Works' models and drawings are unique manifestations of investigative process.