Gary Wolf, AIA, is the principal of wolf architects. His Writing has been featured in Architectural Review and the Boston Review, as well as several books. He Is Vice president of Docomomo New England and Has taught at Wentworth Institute of Technology and Harvard Graduate School of Design. Interested in Contributing to Architizer? Email us at editorial@architizer.com.

In 1962, Boston was in trouble. Residents, manufacturers, and businesses were fleeing the city, leaving behind acres of empty lots and boarded-up buildings. Residents needed a “new Boston,” and that year the city launched a rare open design competition in search of a new city hall that would symbolize—and help achieve—this rebirth.

The two-stage, anonymous competition drew 256 entries, but in the end, the jury unanimously chose a bold, cutting-edge, and controversial design that was the work of “three young architects, two of them foreigners.” This concrete, Brutalist structure would become, David Dillon wrote, “one of the most remarkable debuts in American architectural history” and “arguably the great building of twentieth-century Boston,” according to Douglass Shand-Tucci’s definitive history, Built in Boston.

City Hall Plaza, 1973

Forty-eight pen and pencil drawings by the winning team—comprising Gerhard Kallmann, Michael McKinnell, and Edward Knowles—are currently on view at the Boston Society of Architects’ BSA Space through November 17. The drawings, ranging from small sketches on yellow tracing paper to oversized renderings on mylar, demonstrate the proposed building’s internal organization as well as its response to the site, including specific historic structures. Although its acknowledgement of the past may surprise some—given the widespread demolitions called for by the Government Center master plan, as well as the architects’ own avant-garde proposal—the concept sketches here depict the new building aligned with Faneuil Hall and Quincy Market, creating a juxtaposition of structures from three centuries. Both the popular and professional press featured such drawings from the competition, including a 16-page spread in the Yale Architectural Journal’s Perspecta 9/10, edited by then-graduate student Robert A. M. Stern.

First Sketch – Site Section Looking North. Gerhard M. Kallmann and Michael McKinnell. Image courtesy of Historic New England.

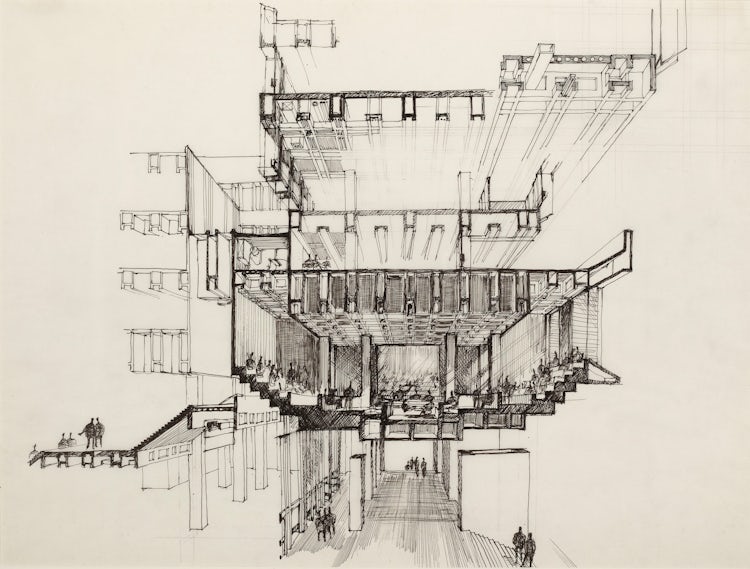

Kallmann’s distinctive section-perspective drawing technique seen here allowed the simultaneous exploration of both interior spaces and building systems. His study of the City Council chamber floating above the plaza entry depicts the architects’ creative re-interpretation of the typology of city halls, in which civic meeting rooms were traditionally located above open ground floors (familiar from European antecedents, and from Faneuil Hall as well). By expressing the form of the Council chamber outside and also from below, this drawing also suggests the architects’ belief that a civic structure should expose the primary spaces of government, instead of concealing them inside an unarticulated building mass.

Council Chamber Study Looking South. Gerhard M. Kallmann. Image courtesy of Historic New England.

McKinnell’s large perspective drawings chart the evolving appearance of City Hall’s exterior, influenced by both the groundbreaking work of Le Corbusier and classical architectural precedents. The design of City Hall’s upper floors, lofted above tall concrete piers, evokes the massing of Le Corbusier’s La Tourette and, at the same time, ancient ruins. Closer to home, its repetitive concrete frames echo the trabeated granite structure of Alexander Parris’ Greek Revival Quincy Market a few hundred yards away.

Le Corbusier, Sainte Marie de La Tourette, 1960.

The drawings for the plaza-level floor plan demonstrate the building’s proposed openness, unusual for a seat of government, with an array of columns in place of solid walls. (Today, haphazardly placed “temporary” barricades compromise this unique attribute—inelegant reactions to 9/11 that still await creative redesign.) The drawings reveal a floor plan intended to welcome pedestrians to this public structure, despite the perhaps less inviting impression that the building’s concrete surfaces would ultimately present for some observers.

Often it is City Hall’s Brutalist concrete material that attracts attention today. Some celebrate it, as part of the revival of interest in mid-century architecture and the widely heralded restoration of similar landmarks such as Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art and Architecture Building—promoted by both the late Ada Louise Huxtable and the Boston Globe’s editorial page as an example for Boston to emulate. Others bemoan the concrete, in combination with the effects of decades of deferred maintenance, and, especially, the unbroken expanse of City Hall’s brick plaza (although this is currently being redesigned to introduce significant new landscaping and trees).

In reviewing the subsequent career of Kallmann McKinnell and Wood—the firm that these competition drawings launched into being—historians have compared their influence in Boston to that of Charles Bulfinch, H. H. Richardson, and Charles McKim. The office would go on to design buildings from the Student Center at the University of Massachusetts on Boston’s Columbia Point to the Carl B. Stokes U.S. Courthouse in Cleveland, from New Jersey’s Becton Dickinson Headquarters to the University of Kentucky’s Young Library, from the U.S. Embassy in Bangkok to the headquarters of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons in the Hague (the just-announced Nobel Peace Prize recipient).

US Embassy Bangkok, Thailland. Kallmann McKinnell and Wood Architects, 1996

Design ideas that first appear in this exhibit’s drawings for City Hall resurface in the architects’ later works: the Hynes Convention Center’s attention to its historic setting in Back Bay Boston, the open plan of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in Cambridge, the Stokes Courthouse’s shaping in response to its urban waterfront site, the expression of incompletion in the fragmented forms of the Arrow International Headquarters in Reading, Pennsylvania. These examples of what McKinnell has called the “ancient craft of architectural drawing” encourage such examination, and also confirm Peter Eisenman’s observation that “If modern architecture lives in America, it lives in the minds, the hearts, the eyes and the hands [of Kallmann and McKinnell].”

Boston City Hall, Perspective Looking North, Second Floor North Hall, by Gerhard M. Kallmann. Image courtesy of Historic New England

These drawings depict the gestation of a unique building during an era of optimism and hope; husbanding that structure for the future is the task of the present. As with other public buildings of its era, Boston City Hall today needs attention to lighting, signage, HVAC systems, finishes, and furnishings, along with basic maintenance (window cleaning!) and, more dramatically, sustainably oriented “greening.” As for those who call for the demolition of City Hall in favor of high-rise towers on its site, the blunt comments of Professor Emeritus Eduard F. Sekler of Harvard merit consideration. In a letter to the Boston Landmarks Commission, he supported Boston City Hall “as a most important Landmark,” and wrote, “whether it is considered beautiful and liked at a given moment is irrelevant since taste changes from generation to generation.”

Boston City Hall Drawings run through November 15 at the Boston Society of Architects’ BSA Space Gallery, in Boston, Massachusetts.