Architizer's new image-heavy daily newsletter, The Plug, is easy on the eyes, giving readers a quick jolt of inspiration to supercharge their days. Plug in to the latest design discussions by subscribing.

Since his comic debut in 1939, Batman has remained bound to the begrimed and lawless streets of shadowy Gotham City — the place where Bruce Wayne was orphaned and where Batman’s origin story began. While the name and location of Batman’s hometown Gotham City have always remained a fictional addition to the state of New Jersey, like many other cities throughout the DC Universe, Gotham has varied in its physical portrayals over the decades. As Batman grew in popularity and moved off the printed page to become the larger-than-life screen presence we see today, Gotham has evolved alongside the city’s tortured nocturnal antihero.

In the 80-years since the initial introduction of Gotham City, the deranged urban landscape has been refashioned and reinvented, with each successive iteration espousing dramatic transformations over the years. Each writer, director, designer and illustrator conjured their own landscape for The Caped Crusader to inhabit. Across these various representations, the architectural influence of Gotham is most commonly a mix and match of Art Deco, Art Nouveau and Gothic architecture, honing in on the elaborate spires, pointed arches, and ornate decoration often featured throughout the city and piercing the skyline. While each iteration was born from the social and political messaging found within the storylines of Batman, the creators used various actual buildings and architects to inspire the decaying airless aesthetic of troubled Gotham City.

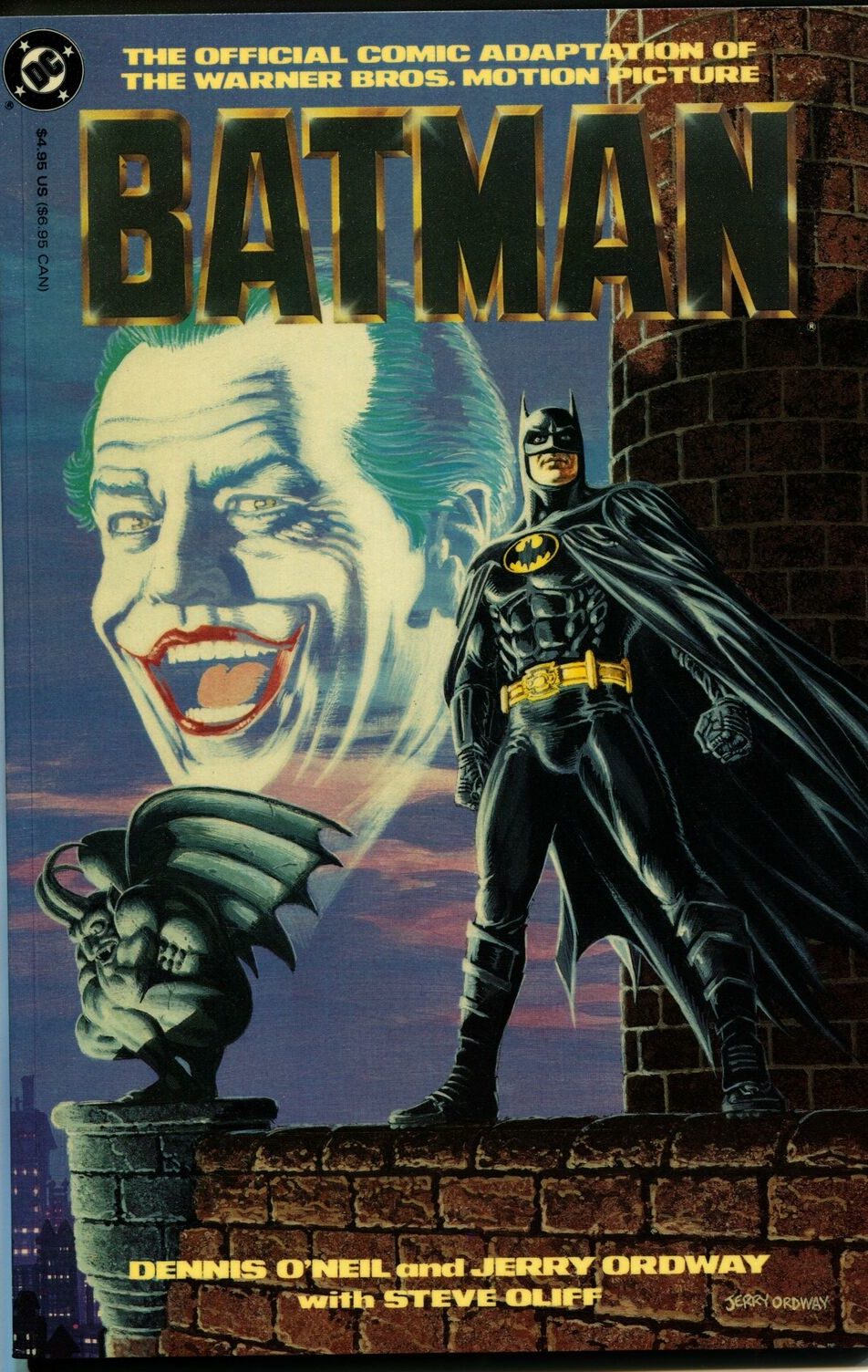

Batman, Film Comic Adaptation (1989) Authored by Dennis O’Neil, Illustrated by Jerry Ordway and Steve Oliff

Through the 40s and 50s, Batman’s world was bright, colorful and wholesome, capitalizing on a broken America in need of hope and light. It was in 1970 when the late Dennis O’Neil began authoring the comics that Gotham started to reflect the brooding inner psyche of the cities defender that we recognize today.

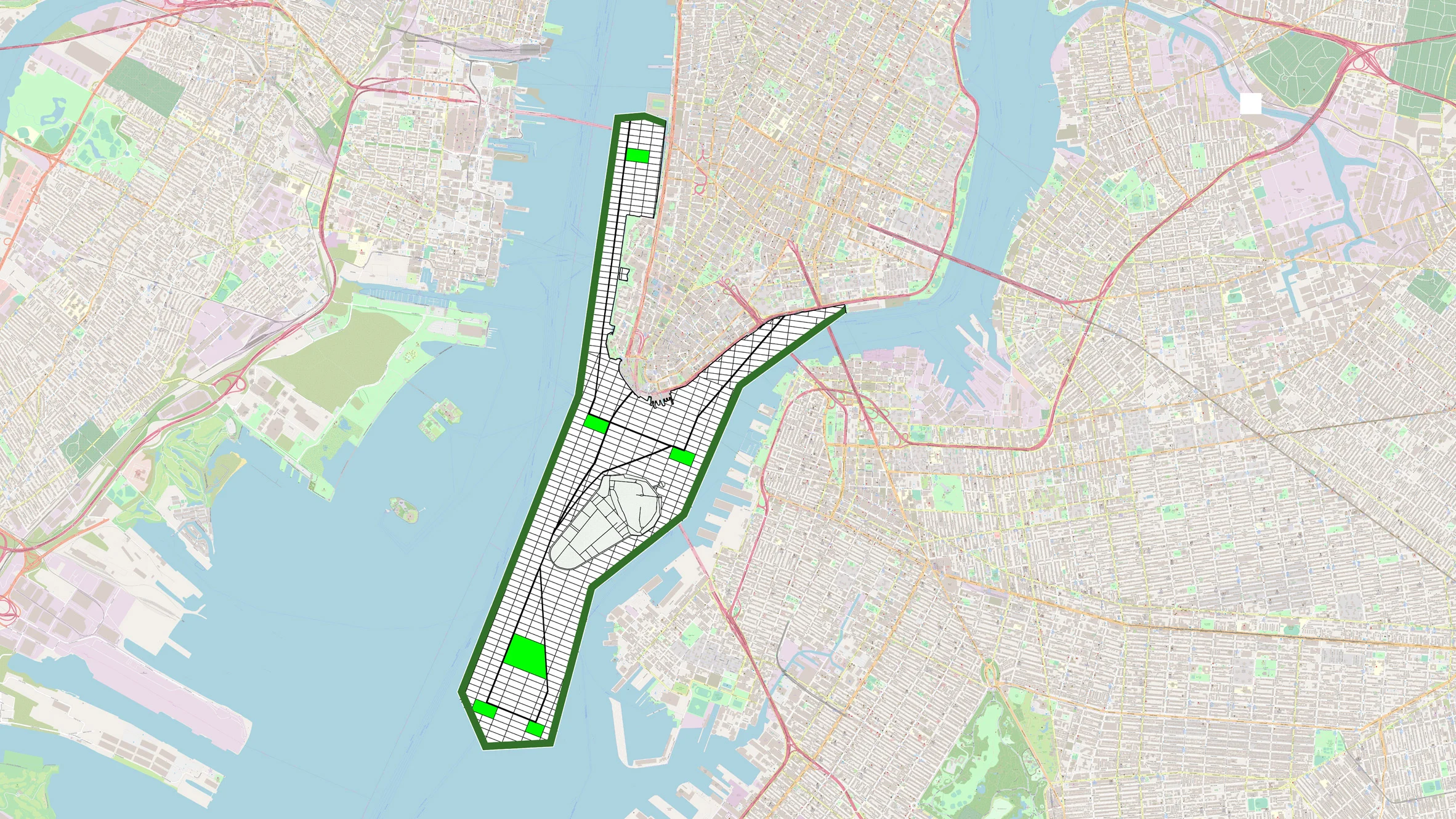

O’Neil said that Gotham took on the shape of “Manhattan below 14th Street at 3 a.m., November 28, in a cold year,” Gotham, in his mind, exuded a timelessness filled with 19th-century, gargoyle-heavy architecture and towering back alleys. The Gothic architecture style heavily influenced his portrayal, and his gloomy depiction of the fictional city streets began a long history of fighting in the shadows for the masked vigilante.

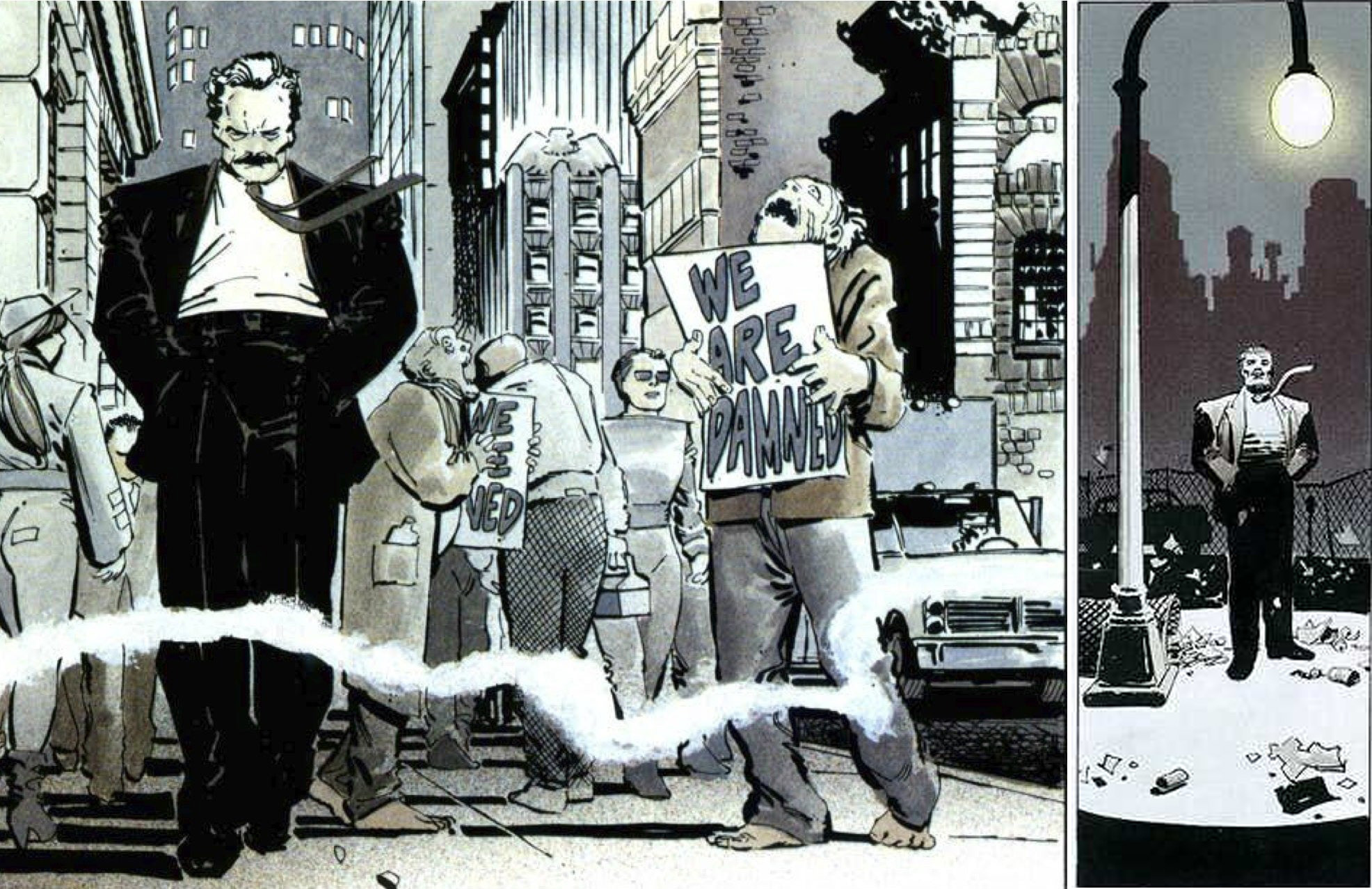

The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller (1986)

In 1986 Frank Miller introduced the world to the limited comic series The Dark Knight Returns. The famous four-issue run imagined Gotham’s terrorized and sickly streets as a landscape abandoned by reason and pride, a characteristic reflected in the story’s main protagonist. In his illustrations, towering buildings regularly overshadow the streets below, suffocating the city dwellers below and their unusual silhouettes constantly looming in the background. Miller’s vast, imaginary city was the true beginning of the exploration into Gotham City as a fantasy architectural landscape.

Gotham City Police Headquarters by Anton Hurst

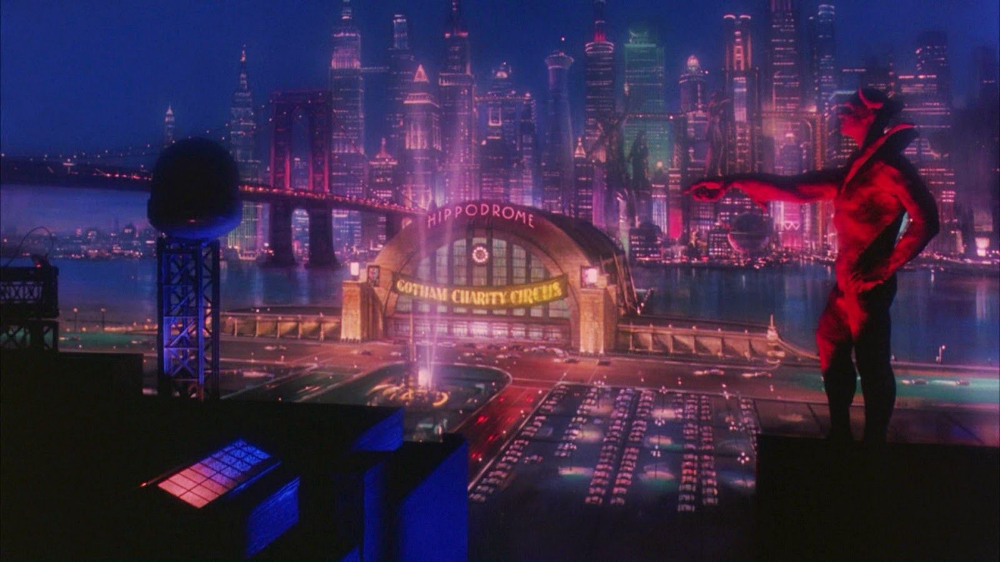

Batman (1989) by Tim Burton

When Batman was placed in the hands of Tim Burton just three years later, he was able to visualize Gotham’s dark potential for the big screen. With the help of the talented sketch artist and production designer Anton Furst, Burton’s film would go on to establish Gotham as a grotesque and rotting site of urban decay. Furst’s initial sketches show an almost impenetrable array of buildings which illustrated the idea he expressed that Gotham was “all the elements of Manhattan exaggerated.” Inspired by New York’s blend of classical structures on the back of years of neglect, Furst “imagined what it would have been like if it had been run by a criminal organization for a long time.”

From the first shot of Tim Burton’s Batman, Gotham City is a twisted mess of gothic spires and arches, with leaning buildings towering over the darkened streets; it gives a vivid sense of place and is deeply reminiscent of German Expressionism. Furst explained his jarring composition of architectural styles combined Italian Futurism with the expressionist work of Antoni Gaudi and Frank Lloyd Wright with modernism, brutalism and Japanese architecture in there too to expand on the chaos and confusion. Inevitably, after the film’s success, Furst won an Oscar for his interpretations of Gotham. The 1989 vision of the city remains one of the most memorable and well recognized, even having a profound effect on the way Gotham has since been represented in the comics.

Batman Forever by Joel Schumacher (1995)

Batman Forever by Joel Schumacher (1995)

After two gritty movies, the Warner Bros studio worried that Batman’s aesthetic had tipped to the side of ‘too dark’ and feared continuing the convention would fail to connect with the comic book reader who was first drawn to the mysterious millionaire. Director Joel Schumacher was hired to take the reins in Batman Forever (1995) and return Gotham to its lighter origins. The design explored the creation of a ‘living comic book”. The result was a stark contrast to Furst’s and Burton’s nearly colorless vision of Gotham. Schumacher and production designer Barbara Ling lightened the palette and softened the tone to complement the exuberant performances from Jim Carrey and Tommy Lee.

The larger-than-life buildings that were the backbone to all of Gotham’s interpretations remained in Schumacher’s interpretation. Sprawling streets, underground tunnels and menacing alleys persisted; yet, Ling’s design moved away from the ornate gothic style to incorporate modernist Japanese architecture with Russian constructivism all overlayed with surreal neon hues —mixing styles in a similar but separate fashion to her predecessors.

Schumacher’s second take on Batman and the City of Gotham in Batman & Robin (1997) would go down in history as one of the worst superhero movies of all time.

Batman Begins by Christopher Nolan (2005)

We saw very little of the tormented roof dweller until 2005, when the Dark Knight was revived by directing superstar Christopher Nolan. In a major break from the traditional New York landscape we had become accustomed to seeing Batman inhabit, Nolan decided to situate Batman Begins (2005) in Chicago, knowing it contained a variety of subterranean levels, crime-riddled history, and the kind of gothic architecture only available in a few other East Coast cities.

Nolan’s notion was to achieve much of the filming for Batman Begins and the rest of The Dark Knight series in real life, stepping away from the distorted fantastical architecture of previous versions and instead relying on the immense number of Gotham-esque buildings that had inspired the city in the first instance. The realness captured throughout the movie established Chicago as a comic book city and undoubtedly played a role in the movie’s ultimate success.

While Nolan moved away from Chicago for his later movies, in the two subsequent pictures, The Dark Knight (2008) and The Dark Knight Rises (2012), Gotham was conceived in the same manner, as a place easily imagined to be real, inspired by real places, recognizable and eerily familiar. Throughout these movies, Nolan shifts from Manhattan and Pittsburgh to stitch together his imaginary city full of disarray. The idea for Gotham in Nolan’s movies aligns with the way people feel about Batman himself; someone who is at once real but is also a composite of of different identities, some contradicting.

The Batman by Matt Reeves (2022)

In the latest installment of Gotham’s defender, The Batman (2022) by Matt Reeves, it is satisfying to see the amalgamation of 80 years of Gotham’s architecture come together on-screen as one coherent backdrop. Matt Reeves and his production team have drawn their inspiration from all corners of Gotham’s history in a way that appears fantastical and realistic all at once. Filmed across Glasgow, Liverpool and London, the menacing city comprises actual streets, alleys and graveyards interwoven with New-Yorks Landmarks.

Using digital technologies, the team was able to stitch together a make-believe city, including elevated train lines and towering skyscrapers that are deeply reminiscent of Furst’s original sketches from 30 years ago. Production designer James Chinlund said, “It created this idea that the city has fallen on hard times and had various booms and busts along the way, with a lot of unfinished skyscrapers and partially complete construction projects.” Reeves’s vision combines the gloomy gothic British infrastructure with appropriate modern elements to hold the narrative true to its surroundings. If you haven’t seen the movie yet, this is your chance to visit Gotham in its latest reincarnation.

Architizer's new image-heavy daily newsletter, The Plug, is easy on the eyes, giving readers a quick jolt of inspiration to supercharge their days. Plug in to the latest design discussions by subscribing.