Calling all architects, landscape architects and interior designers: Architizer's A+Awards allows firms of all sizes to showcase their practice and vie for the title of “World’s Best Architecture Firm.” Start an A+Firm Award Application today.

The designers at Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) had what may be a familiar problem. For their new Los Angeles Courthouse, they had designed a minimal interior with a large atrium and an exposed stair that was light, bright and open. It was a dream.

© Bruce Damonte Photography Inc

Then came reality and, with it, the problem. Building codes require guardrails, and rightfully so — all those people accidentally falling off the edge of floors would be a bummer. A federal courthouse also has to satisfy stringent safety requirements that might eliminate options that could work in, say, a small vacation home. Rather than cluttering up the interior with distracting barriers, the designers wanted to have the guardrails disappear as much as possible, ideally by just using simple panes of glass.

But can it really be that easy?

The answer is: Yes, but you need to know what you’re looking for. Architizer talked to manufacturer C.R. Laurence about how they provided the glass guardrails from their standard line of products to create exactly the look that SOM was after.

© Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM)

Daylighting section for Los Angeles Courthouse by SOM

SOM wanted the building to be as sustainable as possible, and the courthouse achieved a LEED Platinum rating. Daylighting played a major role in making this possible. The façades feature a pleated glass skin with opaque panels in east- and west-facing directions that minimize solar heat gain. The massing, materials and detailing are subtle and restrained, in keeping with the aim to create an elegant new federal building in a major American city. The main central space of the building is a large central atrium that is daylit through a glass roof, letting light penetrate deep into the building.

© Bruce Damonte Photography Inc

Skin of Los Angeles Courthouse by SOM

The last thing they wanted to do in that atrium is cover it with busy or opaque guardrails. Transparent glass rails were an obvious solution, but they present some challenges. Will they work with the rigorous safety codes the building will have to meet? And will they be cost-effective and easy enough to maintain to make sense in a large-scale public building? Fortunately for SOM, C.R. Laurence had a product that they knew would work perfectly even under these demanding conditions. The GRS TAPER-LOC Dry Glaze Glass Railing System is built to International Building Code (IBC) standards, and the designers knew that it would meet the rigorous safety standards with relatively little fuss.

This might not seem like an exceptional story. How hard can it be to find a glass guardrail? Well, as it turns out, it’s recently become more difficult to find one that meets international safety standards because of a 2015 change to the IBC that tightens up the definition of guardrails. C.R. Laurence actually designed the GRS TAPER-LOC Dry Glaze Glass Railing System in conjunction with the International Code Council (ICC) to create the first glass guardrail system that conforms to the updated 2015 standards.

Atrium of Los Angeles Courthouse by SOM

Now might be a good time to talk about the difference between handrails and guardrails. Handrails are pretty much what their name suggests: a surface that a hand can hold onto while climbing stairs or a ramp. They are there to provide balance and stability to a person. Guardrails, however, are meant to keep things from sliding off of an edge and down to the surface below.

This means they must be stronger than handrails and be shatterproof so that if they should break, they do not rain shards of glass on whomever may be below. Even relatively small pieces of glass falling off the top level of a tall atrium can be life-threateningly dangerous. To achieve this strength, glass guardrails must be laminated glass with a fortifying membrane sandwiched between, whereas handrails can be single, monolithic panes of glass.

Andrew Haring from C.R. Laurence pretty neatly summed it up:

“In the laminated guardrail, two lites of glass are joined by a rigid interlayer, something structural, so that if something hits that glass, it’s not going to rain glass down below. In that courthouse project, if something hit the fifth-level glass and that just dumps all the way down to the main level, that could absolutely kill somebody … What the laminated guardrail is intended to do is to, one, prevent people from going through and over but then also prevent glass from raining down below.”

© Bruce Damonte Photography Inc

Atrium of Los Angeles Courthouse by SOM

The layered construction of guardrails means that they are much more resilient, but it also creates a potential installation complication. This brings us to the ‘Dry Glaze’ portion of the product’s name. Glass guardrails and other glass products can be dry glaze or wet glaze, which refers to the securing method where the glass meets the surrounding material. Wet glaze systems require expansion cement to be poured on-site to secure the glass, whereas dry glaze systems are mechanically fastened using reinforced polymer compression tapers and require no wetwork to be completely installed. As Haring points out:

“Traditionally, glass railings have been wet-set … You set your glass, you shim and plum it out, and you’re pouring cement in there and waiting for it to set. That’s still done now … It’s messy. If something happens for the owner, say if glass chips or scratches, or they need to move it, the glazing contractor has to chisel out a whole piece of glass.”

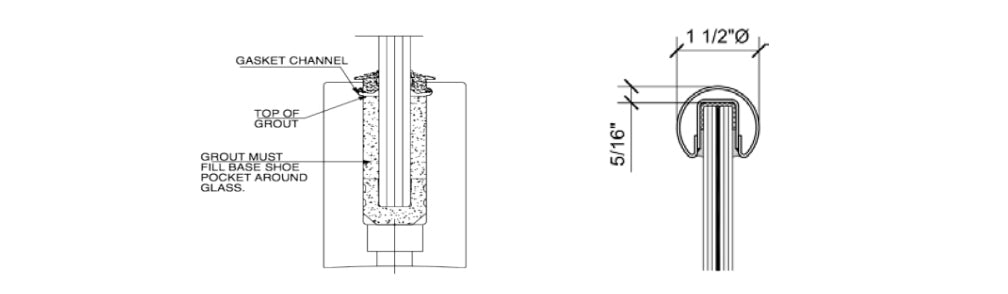

Typical wet-set base detail and cap detail for glass guardrail; images via ICC-ES

Laminated guardrails bring with them an added layer of complication:

“With the laminated guardrail, a lot of these manufacturers that make the interlayer that go between the glass won’t warranty the application if it’s wet-set. A lot of the cement styles don’t react well with the interlayer and they can compromise the system, causing it to either delaminate, discolor and have glass creep, so that’s another area where the dry glaze system becomes advantageous.”

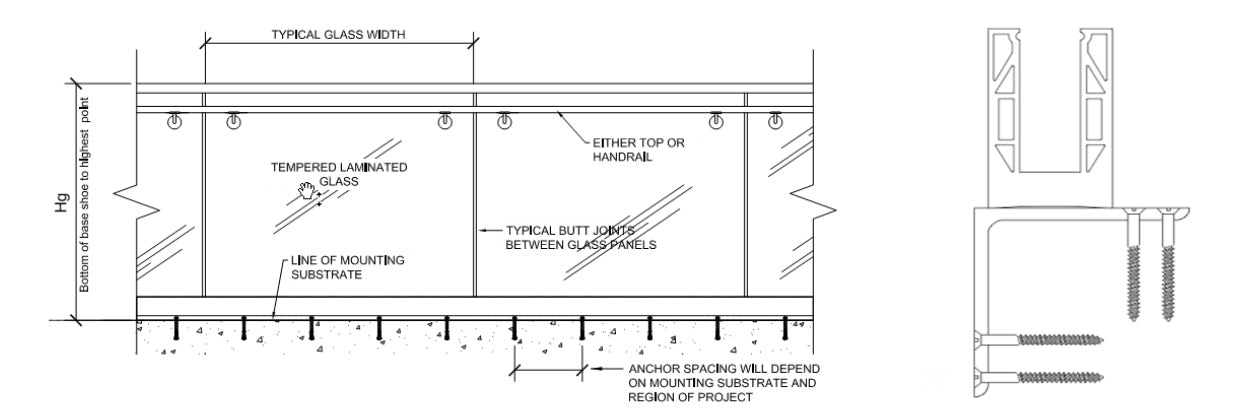

The GRS TAPER-LOC Dry Glaze Glass Railing System uses a base shoe system, which means that the glass is supported by an extruded channel ‘shoe.’ This piece can be hidden into the surrounding structure or be attached to the fascia of a balcony edge.

Typical guardrail and base shoe diagrams; images via ICC-ES

While most designers want their glass rails to be as clear as possible, you can add in a wide range of glass types. You can also do large panes of glass if you want to minimize seams, but Haring had some caution on that point: “The bigger the glass, and you run into deflection issues. There’s nothing in the code that says the glass can or can’t deflect this much … but it can be wobbly,” Haring said. “The owner’s not going to be happy with their fourth-level guardrail having some shimmy in it.”

Another point to keep in mind when it comes to the size of panes is that many codes will have a minimum number of panels that can be used to line a run of guardrail. This is so that there is redundancy in the system holding up the handrail connected to the glass railing. Three panes of glass is a standard minimum. “They want a handrail that’s connecting three different lites of glass to where if one panel fails, a handrail’s still going to hold the other pieces of glasses up,” Haring said.

Guardrail of Los Angeles Courthouse by SOM

A big point of discussion, Haring also said, is whether or not to put a cap on top of a glass guardrail. Many designers like the super-minimal aesthetic, but, he said, they may be disappointed with the edge quality of some laminated glass. The two layers of glass in the guardrail can sometimes slightly unevenly align, which many designers may be unhappy with. A thin cap can be a nice way to cover up any rough edges and also increase structural integrity.

C.R. Laurence manufacturing and research facility; image courtesy C.R. Laurence

C.R. Laurence is an architectural glazing systems manufacturer that has existed for decades. “The company started in the ’60s as mostly a supplier to glass and glazing contractors,” Haring said. Since then, the company has focused on designing and engineering innovative glass hardware systems out of their Los Angeles headquarters and manufacturing facility. “In the last five years plus, we started bringing in 3-D printing capabilities, and that has exponentially increased our R&D teams. We’re able to design and test multiple iterations and just really fine tune a process in an instant.” This in-house research and design capability is what enabled them to partner with the ICC and quickly design a guardrail to the new 2015 standards.

Because the GRS TAPER-LOC Dry Glaze Glass Railing System was designed for the updated 2015 regulations on guardrails, SOM specified it knowing that the product would satisfy local building codes. While there is a variety of options available, going with a known and tested product means fewer headaches both for the architect and for the owner.

Calling all architects, landscape architects and interior designers: Architizer's A+Awards allows firms of all sizes to showcase their practice and vie for the title of “World’s Best Architecture Firm.” Start an A+Firm Award Application today.