One of the most talked-about stories in architecture this year has been Tokyo’s decision to scrap Zaha Hadid’s competition-winning design for the 2020 Olympic Stadium. Fueled by concerns over spiraling costs, public discontentment at the scale of the proposed arena, and mounting criticism from Japanese architects, the city pulled the plug on the British-Iraqi architect’s commission — opening the door for a fresh design by a local firm.

This week, two shortlisted proposals were revealed by the Japan Sport Council: simply titled “Design A” and “Design B.” The firms responsible remain anonymous, but local news reports that the new projects are the works of Kengo Kuma and Toyo Ito, respectively. More closely examining the designs, certain features appear to validate these claims; the timber-framed, plant-lined exterior of Design A echoes many of Kuma’s recent projects, while the light and gently undulating canopy hovering above Design B evokes the sinuous lines of Ito’s work.

The question is: are these proposals equal to or better than Zaha Hadid’s original vision?

Design A – probably the work of Kengo Kuma; courtesy of the Japan Sport Council

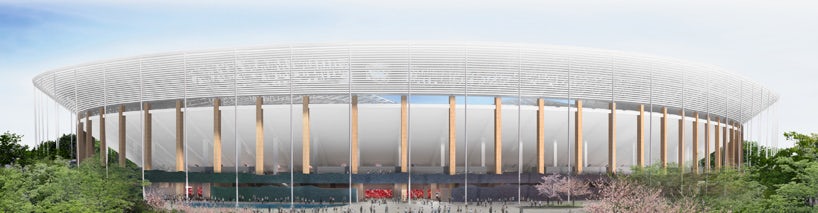

Design B – probably the work of Toyo Ito; courtesy of the Japan Sport Council

Zaha Hadid’s Original Tokyo Stadium. Courtesy Methanoia

Public reaction to the new designs around the web has been peculiar. The negativity that has surrounded this controversial project from the outset appears to be infectious, and the new proposals are not immune. “Two words: #BloodyDreadful … Tokyo has become pure snoozeville,” proclaimed one user in the comments section of ArchDaily’s report on the new designs. Another user remarked: “Banality at its best. Shame on you, Japan.” The derisive outbursts go on and on.

Hold on a moment, though. “Snoozeville?” “Banality at its best?” These comments come following an online outcry over Hadid’s overtly iconic design, which countless commentators labeled overwhelming, ill-proportioned, and lacking in sensitivity toward the context of Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park, home of the famous Meiji Jingū Shrine and garden. It seems that there will always be some that find fault in proposals for an architectural typology that is monumental by definition.

Exterior perspective of Design A; courtesy of the Japan Sport Council

It is arguable that an 80,000-person-capacity stadium will inevitably become the center of attention within its urban locality. With this in mind, an extroverted proposal like Hadid’s can easily be lambasted as an example of architectural showboating. On the other hand, if a more conservative approach is taken — as is the case with Designs A and B — a reserved style on such a huge scale will inevitably fall into the trap of perceived banality or, worse still, triteness. One firm to have struck a positive balance between these two conditions in recent times is Herzog and de Meuron, whose Bordeaux Stadium stands as that rarest of things in sports architecture: an understated icon.

Interior perspective of Design A; courtesy of the Japan Sport Council

Hadid’s swooping, sculptural form won an international competition ahead of many prestigious firms including Populous — architects of London’s Olympic Stadium for 2012 — and many Japanese firms such as SANAA, Azusa Sekkei, and even Toyo Ito, so she must have done something right, surely? For all the talk of scale and design, it appears that Hadid’s biggest problem pertained to procurement and politics: the lack of a competitive tender process raised the risk of construction costs escalating. Additionally, with a persisting sentiment that “local” tends to equal “better” in Japan, the British-born architect faced an insurmountable challenge.

Exterior perspective of Design B; courtesy of the Japan Sport Council

Whether one agrees with the dismissal of Hadid or not, the new designs must be defended. Each looks far less likely to cause outrage on an economic front, and, whichever is chosen, a more compact building footprint will undoubtedly have a lesser impact on the surrounding park than Zaha’s sinuous structure. Furthermore, the considered detailing of both Kuma and Ito will surely mean that the winning stadium is anything but banal in reality — particularly when viewed up close rather than the drone’s-eye view chosen for many of the external visualizations.

Interior perspective of Design B; courtesy of the Japan Sport Council

Returning to ArchDaily’s comments section, one can pick out a few more positive views in between the dissent. “Those who say the designs are ugly obviously do not know anything about Japanese sensibilities,” says one user. “These are waaay better than Zaha’s. Tradition in a contemporary style! That is Japan,” said another. “Way better” might be a stretch — but, with either Kuma or Ito on board, there is hope that the reality can surpass the renderings in Tokyo.