There may be no better way to understand a culture than by understanding its buildings. Architecture is evidence of a society’s aesthetic traditions, its technology, its wealth and resources and how it organizes its people. A culture’s most sacred and important buildings don’t just tell the story of who a people are, but also who they would like to be, how they want to be seen.

The histories of America’s estimated 2,100 mosques, built in Moghul, Turkish, Mamluk, Central Asian, Moorish or Modern styles, tell the story of families from around the world, many of whom have lived in the U.S. for centuries, others temporary visitors passing through. Unlike Christian churches in America, which are happy to shine in public splendor, many mosques are self-conscious about their visibility, aware that they have been and continue to be vandalized in Islamophobic attacks.

The mosques shown here variously blend into the rest of nondescript America’s urban fabric, celebrate the rich architectural styles of the Islamic world or try to abstract the notion of a mosque into something modern and perhaps universal. They might not all be the most fashionable today, but they all have pretty good stories.

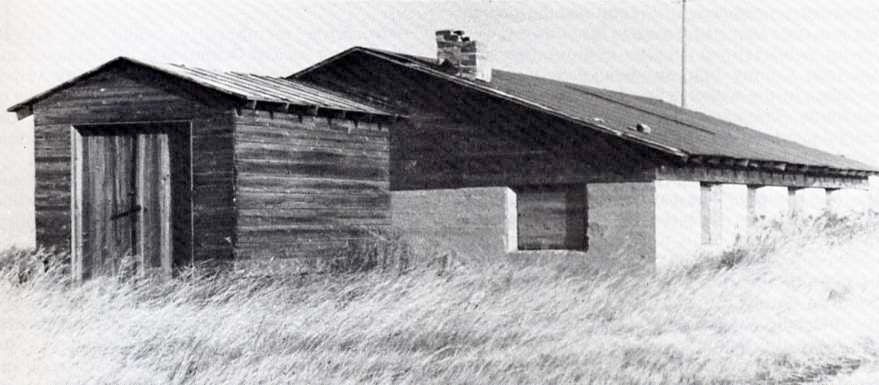

Mosque in Ross, N.D., now demolished; archival photo courtesy New Republic

The Mosque of Ross, North Dakota

Islam in America has humble roots. While the religion has been practiced in the U.S. since before it was a country, the first building designed to be a mosque in North America was probably built in 1929 in rural Ross, North Dakota, by immigrants from what is now Syria, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Its congregation comprised tenant farmers who were offered land by the U.S. government in exchange for clearing and developing it.

Although the Ross mosque, an unexceptional, low-lying building, fell into disrepair in the 1970s as the local Muslim community dissipated, and has since been demolished, the 1934 mosque in Cedar Rapids, Iowa — built by a similar group of immigrants — is the oldest continually standing mosque in the country. The people that built these mosques were part of a wave of immigrants from what is now Syria that traveled to the Midwest from the late-19th century through the beginning of the 20th century, arriving at the same time and to the same places as immigrants from across Europe.

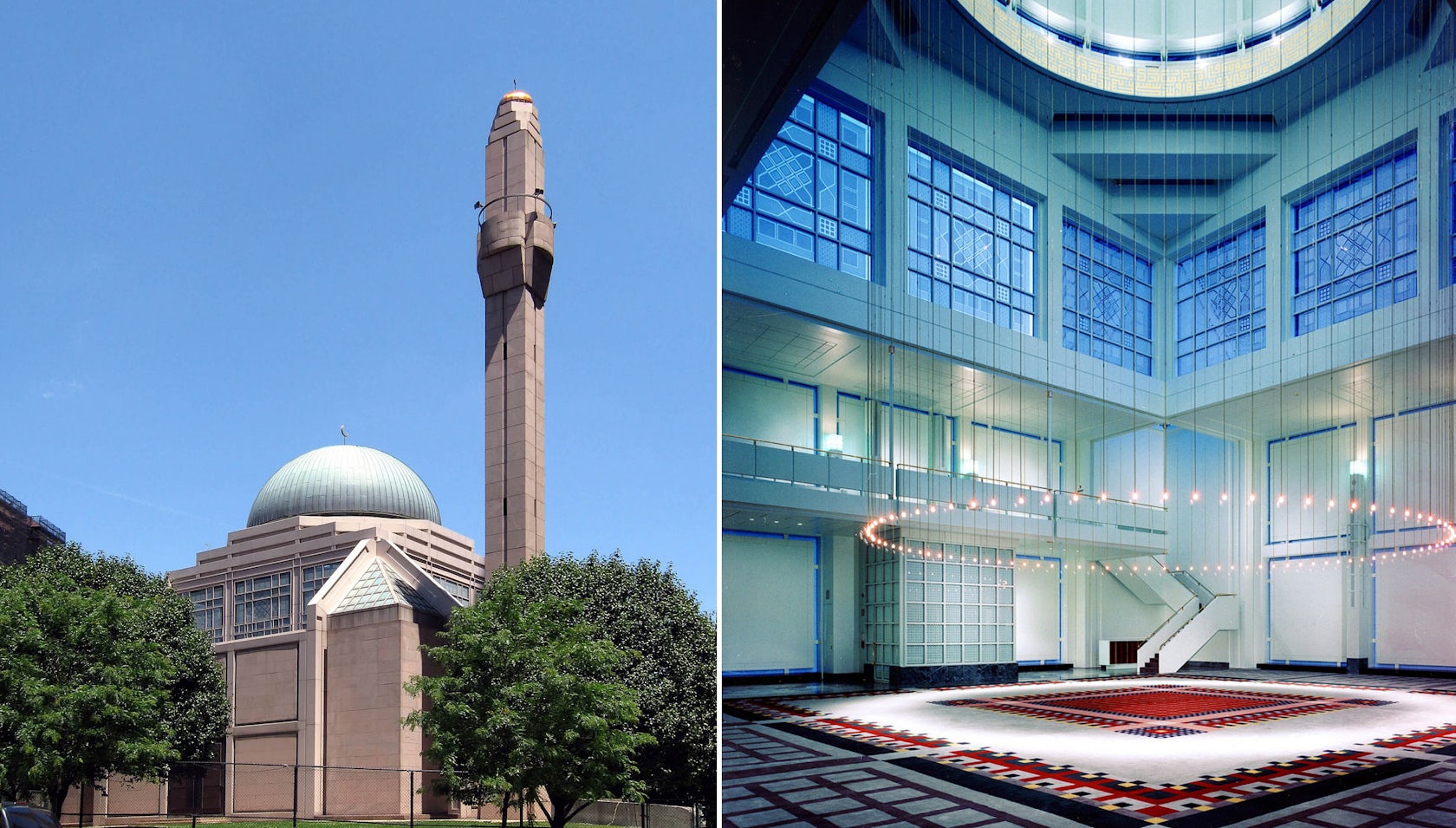

The Islamic Center of Washington, Washington, D.C.; via Carol M. Highsmith – Library of Congress

The Islamic Center of Washington, D.C.

A far cry from a log cabin for immigrant farmers, the Islamic Center and its mosque, built in 1957, are still some of the grandest Muslim structures in the U.S. They were built and decorated under Egyptian state leadership with donations from across the Muslim world and were designed by Italian-Egyptian architect Mario Rossi in an adaptation of 15th-century Mamluk Egyptian style. Notice how the taller interior structure is rotated off the grid of the rest of the building, which is oriented toward the surrounding streets. That interior structure is the mosque proper, the actual room where prayer happens, and one wall of the mosque must be oriented toward Mecca so that worshippers can prostrate themselves in that direction.

The rest of the complex is also known as a masjid, which traditionally functions as a community center, offering services like food kitchens or shelters for the poor. The Center, which has hosted several standing presidents and whose board is filled with ambassadors from major Muslim nations, embodies the traditional formality of international relations. It is the architectural equivalent of an elaborate state dinner, amenable to its hosts while embracing the most refined traditional flavors. It is the apotheosis of traditional mosque design in the U.S.

Interior of The Islamic Center of Washington, Washington, D.C. President George W. Bush is seated in the center; via The Islamic Monthly.

Masjid As-Sabur, Las Vegas, Nev.; photo courtesy Patheos

Masjid As-Sabur

The Masjid As-Sabur in Las Vegas, Nevada, which dates from the 1970s, typifies a very different segment of American Islam — that of the African-American tradition. Some estimates say that around a third of the slaves brought to America from Africa were Muslim, and although many were forced to convert to Christianity, the 20th century saw a return to Islam across African-American communities. The Masjid As-Sabur began under the Nation of Islam, a movement known largely for its association with Malcolm X, although today the Masjid has associated itself with Sunni Islam and has some notable attendees including Mike Tyson and Muhammad Ali (this is Vegas, remember).

The building is lightly decorated by traditional Islamic motifs, most notably by the green molding that wraps the cornice line. Otherwise, though, the building is pretty nondescript, probably because the building was adapted from a former use and the congregation doesn’t have much money to modify it. Furthermore, the congregation may not want to draw too much attention to itself, particularly with styles that may seem out of place to much of Las Vegas. Because threats of vandalism, violence and discrimination are very real for mosques in America, many mosques in this country live in relatively generic buildings, using architecture to integrate themselves into the sometimes monotonous visual landscape of cities like Las Vegas.

Dar al-Islam, Abiquiu, N.M.; via Wikipedia (Abdullah Nooruddeen Durkee)

Dar al-Islam

The Dar al-Islam mosque in Abiquiu, New Mexico, blends into its landscape in a different way. It was designed in 1982 by Hassan Fathy, a prominent Egyptian architect who pioneered stone brick building, natural ventilation and dome vaulting techniques adapted from traditional practices. He translated this architecture from the North African desert to the New Mexican at the invitation of the local, predominantly American-born Muslim community.

The style of the building blends relatively easily into the local Mexican and Pueblo traditions, which were originally inflected with elements from Moorish Spain, in a way refreshing the Muslim influence on local architecture. It’s a blend of architecture from three continents, suitable for both a good Muslim and good American building.

Detail of Dar al-Islam; via ShareAmerica

Islamic Society of North America Headquarters, Plainfield, Ind.; photo courtesy IslamiCity

Islamic Society of North America Headquarters

While the Dar al-Islam physically blends into the New Mexico desert, the Islamic Society of North America Headquarters in Plainfield, Indiana, takes a different tack to adapt to American culture. It espouses the supposedly universal forms of late modern architecture: massive, twisting simple geometric blocks in uniform brick that evoke Louis Kahn’s monumental work. It doesn’t have any domes or minarets.

By the mid-1980s when the masjid was designed, Islam had already started to become something of a bogeyman in American politics, and the congregation wanted to keep a low profile while still creating a celebratory, monumental center. Architecture was how Indiana would see the society and Islam, and it was architecture’s job to put on a dignified, warm face for a community in an uncertain position. Modernism was a sort of architectural Esperanto, a way to find common understanding with the mostly white Christian suburbanites of the Midwest.

Islamic Cultural Center, New York, N.Y.; via Wikipedia (Jim.henderson) and SOM

Islamic Cultural Center

Far from suburban Indiana, the Islamic Cultural Center in Manhattan is used by a diverse group of parishioners, many of whom are visiting diplomats or high-profile business travelers. The Center was designed by SOM and opened in 1991, and it, too, eschews traditional styles, but it does adapt design elements, like the dome and minaret, into a modern language that avoids reference to any particular Islamic architectural tradition.

The minaret was added at a substantial cost ($1.5 million) even though it doesn’t serve the traditional function of a minaret — the regular call to prayer — and is a purely aesthetic addition. Here, modernism is meant less to find a common ground between the congregation and New York and more to establish a neutral setting for the dozens of different nationalities and sects that may use the Center. Islam is both a global and American religion, and the diversity and richness of American mosque architecture illustrate the vitality of the Islamic tradition in America.