Architects: Showcase your work and find the perfect materials for your next project through Architizer. Manufacturers: Sign up now to learn how you can get seen by the world’s top architecture firms.

It is a debate that has raged for decades among architects and architectural journalists alike: How can words encapsulate the intricacies of the built environment without becoming stuck in a quagmire of esoteric soundbites and pretentious clichés? Writing for Architectural Record, renowned critic Robert Campbell coined the word “ArchiSpeak,” a compound word that has come to define the obscure and alienating language that architects are frequently accused of using when describing their work to clients and the wider public.

Thankfully, Phaidon’s book 10x10_3 — an expansive volume on emerging architecture firms by 10 preeminent writers — goes to show that it is in fact possible to succinctly write about buildings and their designers while remaining engaging to those outside the realm of architectural design. Exploring the texts by this distinguished lineup of journalists, editors, curators and architects, certain stylistic traits and linguistic devices can be picked out that serve as a guide to how good architectural writing can emerge. Here are 10 pointers for your consideration:

Bakkegard School by CEBRA

1. Take a Personal Perspective

Bart Goldhoorn — founder and publisher of Russia’s leading architecture journal Project Russia — instantly engages readers by conjuring up intimate imagery and adopting an unusual first-person perspective. He confronts his own preconceptions when describing the refreshing approach of the avant-garde designers at CEBRA:

“A decade ago, when reflecting upon Danish architecture, I imagined quiet, pipe-smoking, corduroy-clad men, a bit dull perhaps, producing responsible and ecologically sound architecture with a light postmodern touch. At best one could expect neat modernism. The architects of CEBRA … do not fit this image of Danish architects.”

Goldhoorn paints a detailed picture of an architectural stereotype before smashing it to smithereens, waxing lyrical about the “wild landscape” and “spectacular, multifaceted” spaces of CEBRA’s Bakkegard School extension in Gentofte, Denmark. The writer’s honesty and personal perspective adds clout to the visceral project description that follows.

Agriculture School by OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen

2. Harness Visceral Imagery

As a highly visual construct, architecture is best framed by words that conjure emotive images in the mind of the reader. London-based writer and curator Shumon Basar — a former employee at Zaha Hadid Architects — describes an installation by OFFICE Kersten Geers David Van Severen using highly evocative language:

“Hundreds and thousands of brightly colored confetti were strewn across the floor, a carpet of delicately disorganized paper detritus. A few black chairs were scattered about. The rest of the pavilion seemed empty, almost abandoned, bereft of the usual feverish desire to explain, show off, divulge, or disclose.”

This poetic observation of After the Party — an artwork examining the fleeting nature of the Venice Architecture Biennale — alludes to the wider philosophies of this experimental practice, encouraging us to mentally immerse ourselves within the firm’s multilayered works.

The Mountain by Bjarke Ingels Group

3. Ask Rhetorical Questions

While most architectural journalists will be wary of Betteridge’s law — “Any headline that ends in a question mark can be answered by the word no” — there are some instances in which questions can be utilized to strengthen an argument. New York–based architect and critic Joseph Grima’s introduction to his analysis of BIG’s rise to prominence is a case in point:

“To understand the true measure of the accomplishments of Bjarke Ingels … consider this: when was the last time reporters from every corner of the world were seen scrambling to cover the opening of a building by a thirty-three-year-old architect?”

This question need not be answered, of course; it is intended purely to emphasize BIG’s unparalleled achievements for such a young firm. Grima takes great joy in describing the concepts behind the firm’s seminal Mountain housing project, recounting BIG’s ingenious idea to “spread the housing on top of the parking like jam on bread.”

Leaf Chapel by Klein Dytham Architecture

4. Master Metaphors and Similes

When trying an unfamiliar food, we often ask the question: “What does it taste like?” Seeking clarity via comparison appears to be an instinctive human characteristic, and this characteristic also applies to architecture, for which metaphor and simile can provide valuable insight into the subtle qualities of a space. Andrew Mackenzie, the editor-in-chief of Architectural Review Australia, illustrates this point with his description of a project by Klein Dytham Architecture:

“A good example is the Leaf Chapel in Kobuchizawa, a wedding chapel conceived as two leaves. One is glass and stationary, the other perforated white steel that lifts as the groom lifts his bride’s veil.”

For the vast majority of readers who will never have the chance to stand inside the chapel themselves, references to leaves and the bridal veil offer a tangible vision of the building’s unique features.

SGAE Headquarters by Antón García-Abril and Ensamble Studio

5. Use Personification

Beyond describing physical attributes of architecture, more abstract, playful adjectives and idioms can enliven your writing and elevate it above purely academic prose. Architect and professor Carlos Jimenez utilizes such linguistic gymnastics to great effect in his article on the extraordinary SGAE Headquarters by Antón García-Abril and Ensamble Studio:

“The SGAE is a porch-like building whose elongated screen wall is a marvelous concoction of tumbling and irregular granite pieces, all held captive in a resilient dance of weight, light and gravity.”

Words and phrases such as “tumbling,” “held captive” and “dancing” lend the architecture dynamic, human-like qualities, encapsulating the drama of a building full of tension, weight and theatrical contrasts in scale.

QVII apartment building by McBride Charles Ryan; image courtesy MCR

6. Set the Scene

A carefully crafted description of a building’s context can provide a wealth of insight into the social, economic and cultural backdrop of a project in a single sentence. Andrew Mackenzie’s introduction to McBride Charles Ryan’s QVII apartment building is a classic example:

“In a suburb of Melbourne, amid the quaint worker cottages interspersed with bulky max-lot town-houses and Regency style rip-offs, stands a small haven of sheltered accommodation, a budget job of plain, unaffected language.”

Having set the scene with a series of en pointe adjectives, Mackenzie goes on to describe the “material versatility and civic countenance” of the project, which is given extra resonance by that vivid description of the surrounding context.

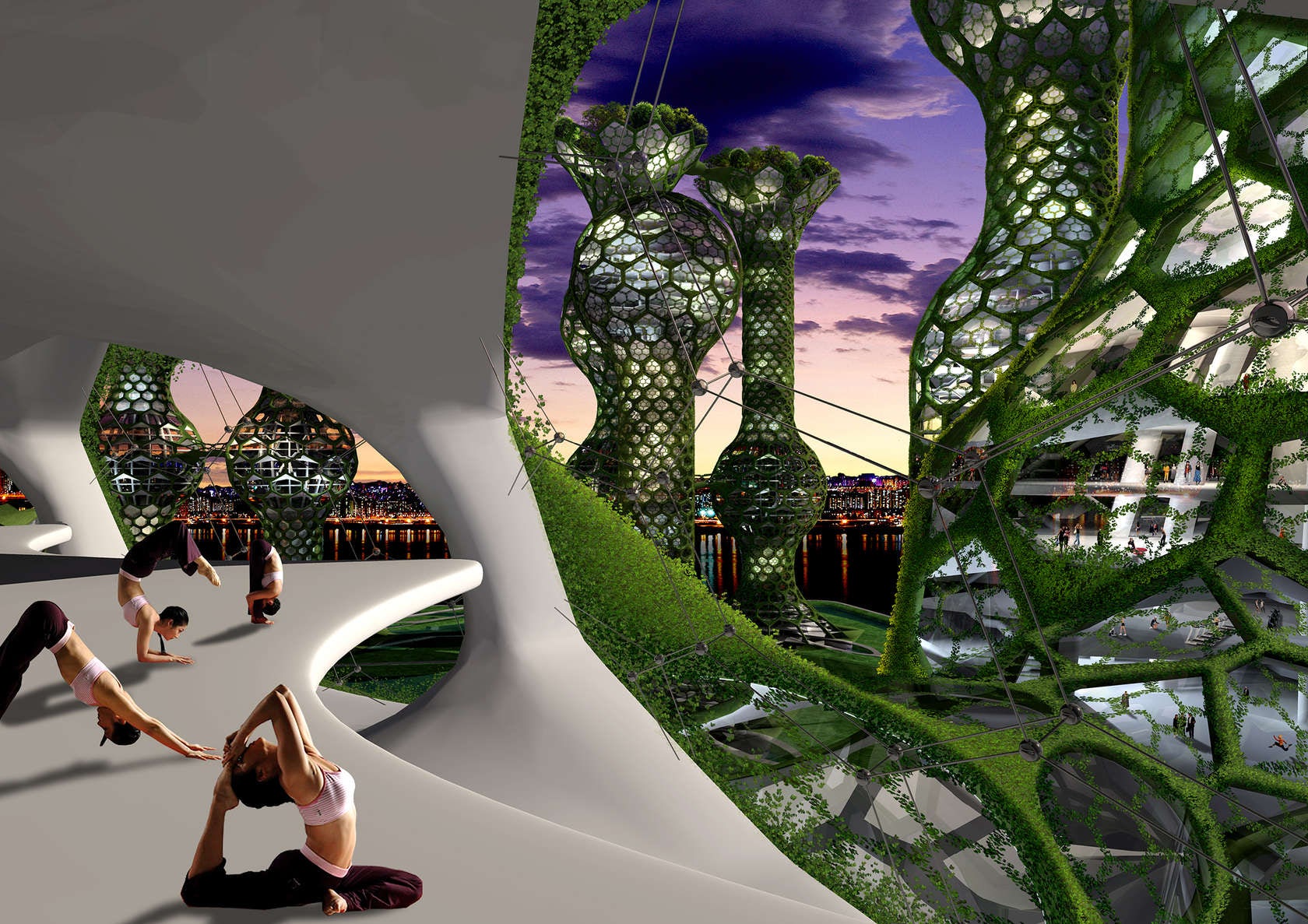

Seoul Commune 2026 by Minsuk Cho; image courtesy Mass Studies

7. Kick Off With a Quote

While this “play” shouldn’t be repeated too often, opening with a quote can add real impact to an essay on an architect’s work, particularly if that architect makes an impactful statement that can provide telling context for the subsequent article. Take the case of Minsuk Cho of Mass Studies, whom Joseph Grima quotes at the outset to instantly engage readers with the plight of the youth in his home country:

“I think there is a struggle going on in the minds of the younger generation,” Minsuk Cho observed in a recent interview, speaking of the challenges facing architects in his native Republic of Korea. “What is ‘Korean-ness’ at this moment in time? What is our relationship to this tradition, to the architectural identity of this culture?”

Grima goes on to outline Cho’s search for the answer to these questions using radical projects such as Seoul Commune 2026, a vision of the future for this fast-changing metropolis. The opening, straight from the source, instantly captures the ambitious, ‘big picture’ thinking of this groundbreaking Korean firm.

Art Deco; image courtesy ArandaLasch

8. Apply Some Dry Wit

The satirical geniuses of Design With Company have shown us that architecture can be funny, but there are also plenty of opportunities to use some dry wit to add impact to your argument and make it more memorable, to boot. Shumon Bazar’s opening gambit for his piece on ArandaLasch is a case in point:

“If ornament remains a crime, exactly 100 years after Adolf Loos made the accusation, then ArandaLasch is guilty as charged. However as everyone knows, crime pays.”

This clever commandeering of an old modernist adage takes a playful swipe at the common theoretical hangups of many architects while immediately framing ArandaLasch as mischievous rebels of the profession. This framing not only brings a wry smile to one’s face, it is also adds weight to the rest of Bazar’s piece on this avant-garde studio’s experimental work.

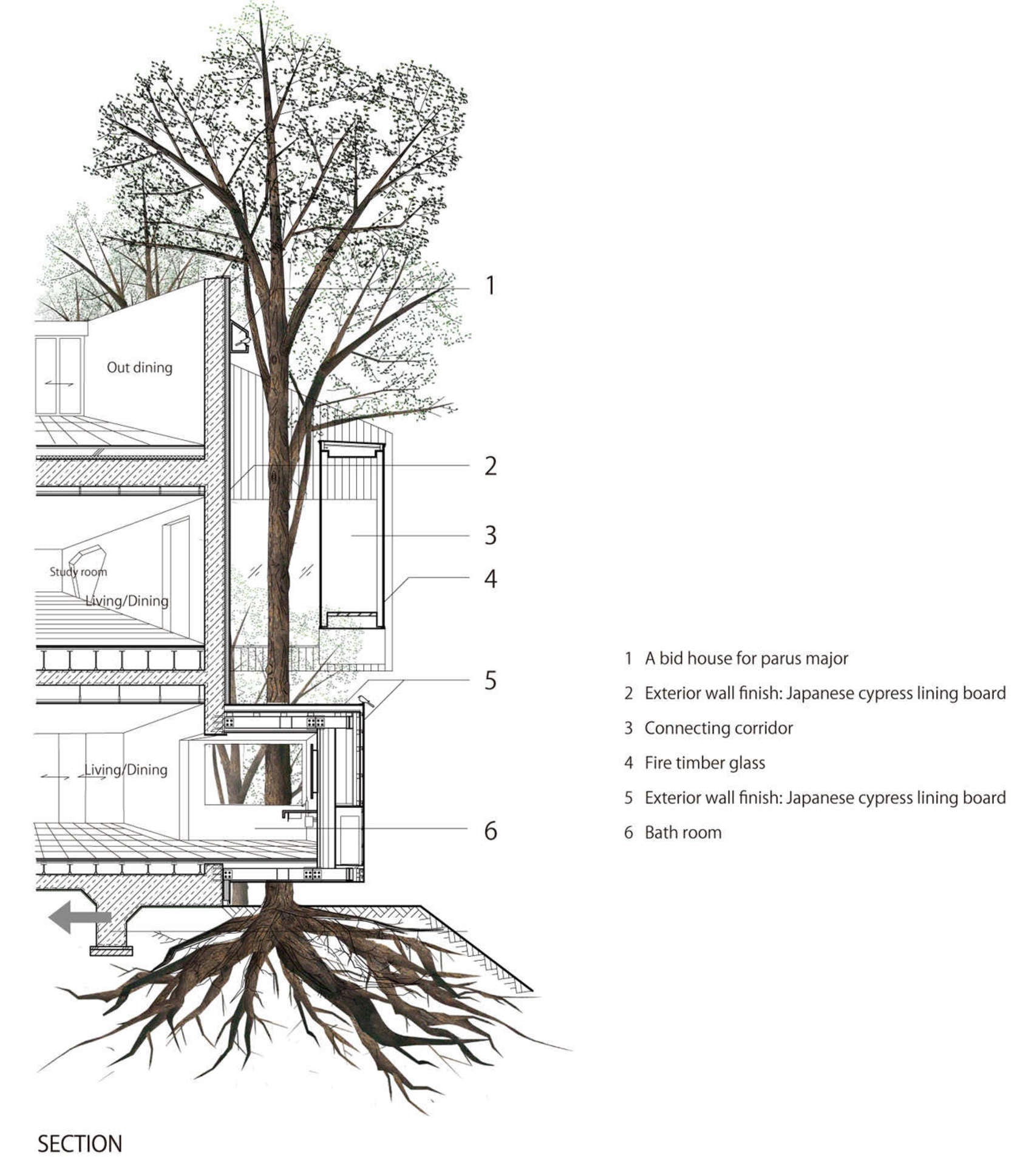

Dancing Trees, Singing Birds, Tokyo, Japan; image courtesy Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP Architects

9. Inject Emotion

As any architect who has worked through the night to complete a project before their deadline will tell you, architecture is an emotional business, but, beyond the travails of the studio, great buildings engender bursts of inspiration, passion, delight, even love. Architect Kengo Kuma identifies this strength of emotion in the work of Hiroshi Nakamura & NAP Architects:

“The most important part of falling in love is not to explain why, but to sing the praises of one’s beloved, and Nakamura does exactly that. When he fell in love with wood, for example, he built a gabled shape that resembles a wooden cottage on an island. This was because he knew that a love song for wood could best be expressed through shape.”

Kuma’s emotive language captures the poetic undercurrents within Nakamura’s work and succinctly describes how they become physically manifested within each project.

Ai Weiwei with his Sunflower Seeds installation at Tate Modern, London, United Kingdom; image via Zimbio

10. Do It Your Way

While there is clear value in understanding the benefits of an expressive vocabulary, good sentence structure and succinct language when writing about architecture, there is also an argument in favor of creative freedom. The built landscape is so complex that each one of us perceives it differently, and this variety can make for powerful and often provocative prose. On the final page of Phaidon’s book, Chinese artist Ai Weiwei’s reflection on the role of architects in relation to the 2008 Sichuan Earthquake provides a potent example:

“Architects do not cause human need; architects merely write the lyrics that make life’s song something we want to listen to. And some architects become the candlelight and sweet whispers that accompany the rape of the environment.”

Weiwei’s loaded choice of words causes us to question our preconceptions not only about language, but about architecture itself. His tone is at once poetic and confrontational, full of visceral force. While one may not agree with the artist’s viewpoint, one thing is clear: This style of writing sticks in the mind long after one closes the book.

Want to see more architecture critics’ favorite projects? Check out Phaidon’s book 10x10_3.

Research all your architectural materials through Architizer: Click here to sign up now. Are you a manufacturer looking to connect with architects? Click here.