There is no easy way to write about the Grenfell Tower fire. Not only was it a particularly horrific tragedy where more than 80 people died, it is also bound up with the byzantine complexities of building regulations and approval processes. Because of how many codes, change orders and design decisions go into a single building, it’s not easy to identify a single point at which the building process failed its residents.

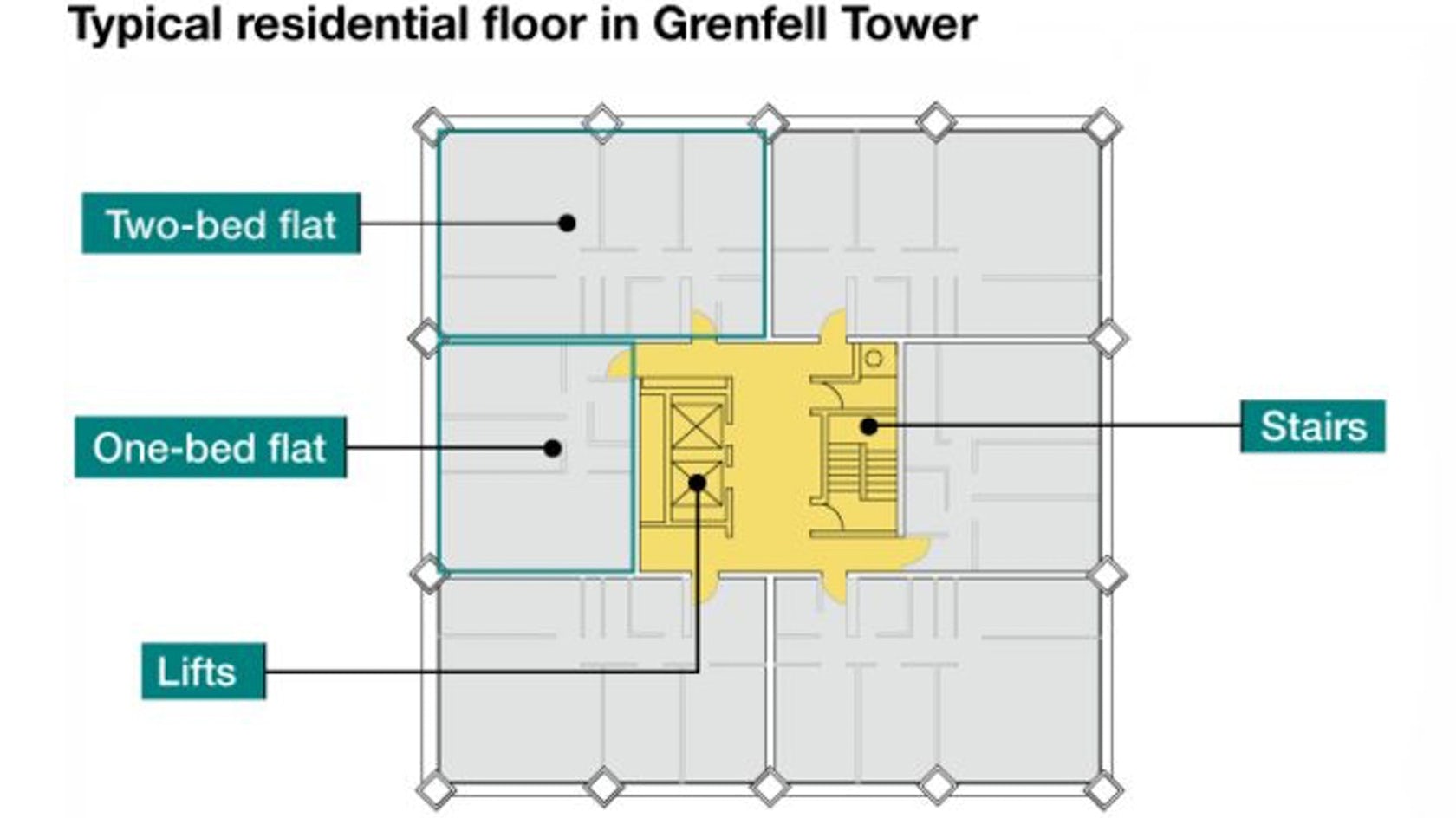

What is clear is that the fire spread quickly through the aluminum cladding and that other countries, like the United States, have not allowed that particular type of metal siding to be used on buildings that tall. The tower had other problems that compounded the dangers of the cladding. Because it was built in the 1970s before many modern safety regulations took effect, it had only one stairwell, lacked sprinklers and fire doors and there was no centralized alarm service. A tower like Grenfell could not be built today.

Typical floor plan of the Grenfell Tower showing the single stair available for exit; image by Studio E Architects, via the BBC

What went wrong?

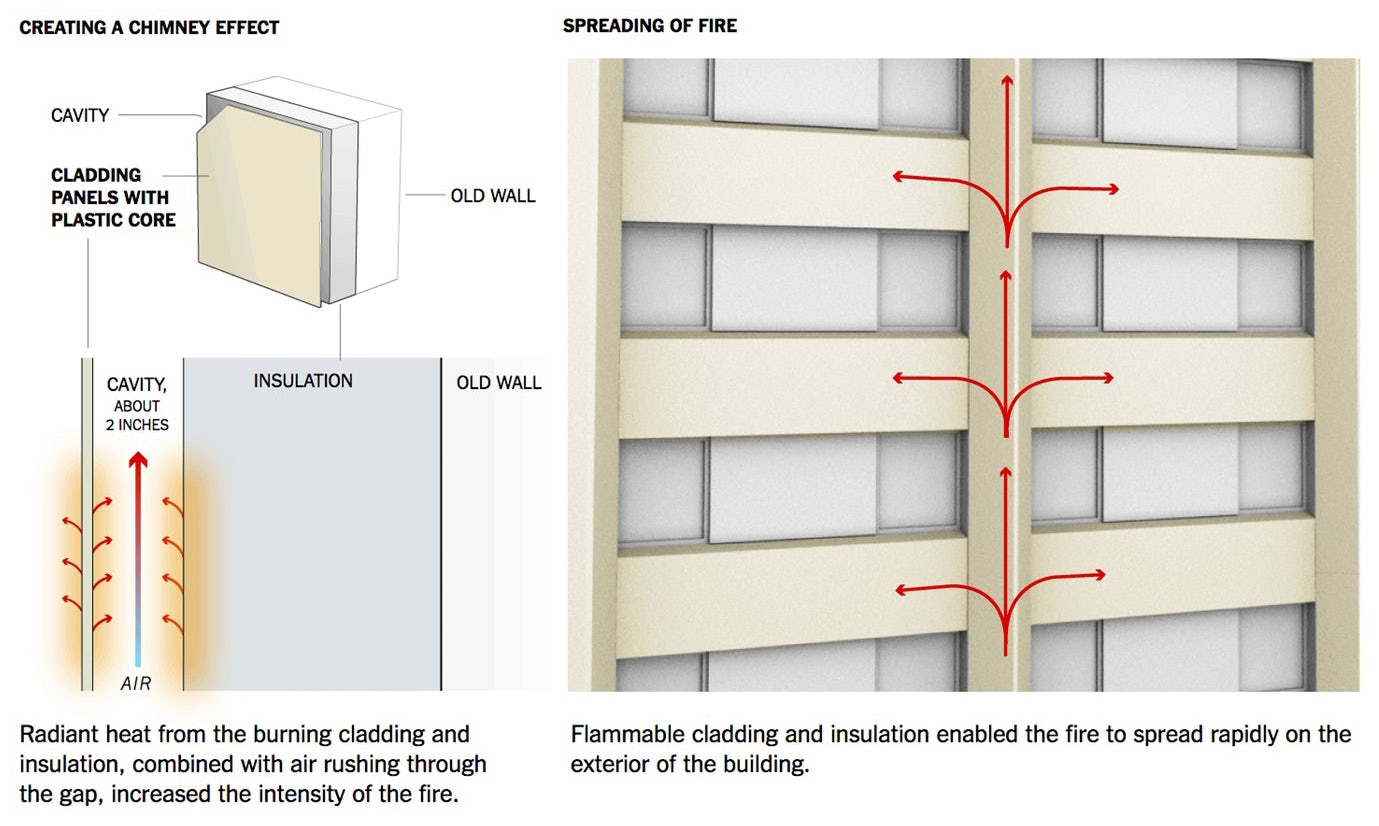

The biggest problem at Grenfell was the aluminum cladding. Installed in a 2016 renovation, the product used in the building is composed of two layers of 3-millimeter-thick aluminum sheeting around a flammable polyethylene core. In many other countries, this kind of product is not approved for use in buildings of this height.

Taller buildings have more stringent fire safety regulations because it is significantly harder to both extinguish the fire and remove people from danger. Some substitute products have the same triple-layer construction but with a more fire-resistant core material, while others comprise simple, single-layer zinc metal sheets. Both of these were options for Grenfell, and a more fire-resistant option was going to be used until it was value-engineered out.

The problem was not just the cladding itself, but also how it was installed. Because it was retrofitted onto the original concrete building, there was an airspace between the cladding and a layer of insulation. This airspace acted like a chimney that the fire quickly spread through. Again, this kind of installation would have been avoided in other countries, including the United States, that require in situ testing of materials before they can be used on buildings this size.

Diagrams showing the gap between the flammable aluminum cladding and the building’s insulation. It was through this gap that the fire spread; image by Mika Gröndahl, via the New York Times.

Who is to blame?

While the local municipal government council has attracted scorn for pressuring the contractor to reduce costs by using the cheaper more-flammable cladding option, it was still entirely legal and code-compliant to use the cheaper product.

Every architect has worked with a client that has forced her to select a cheaper, inferior material. There is only so much pushback a contractor can be expected to give to a cost-cutting client. A local council as flush with funds as the local Kensington and Chelsea council could certainly spend more on providing public housing, but they cannot be reasonably expected to know the relative dangers of specific products.

Leaked document showing the local council pushing the contractors to use a cheaper cladding option; image via The Times of London

Ultimately, the responsibility comes to the building regulatory agencies that have allowed a product to be used in an unsafe manner. The New York Times reported on how Brian Martin, “the top civil servant in charge of drafting building-safety guidelines,” repeatedly tried to limit regulation on building products, even as smaller fires have suggested that they are dangerously lax.

And even after reports emerged of the panel’s flammability around the world, Mr. Martin’s agency refused to institute more stringent regulations, claiming that they would be against business interests. As the Times reported, “the construction industry appears to be stronger and more powerful than the safety lobby,” said Ronnie King, a former fire chief who advises the parliamentary fire safety group. “Their voice is louder.”

The Grenfell Tower; photo via The Independent

What is an architect to take away from this?

It is not practical for an architect to second-guess every single safety regulation and code operating in a single building. There are hundreds, covering everything from ramp angles to sink heights. Architects, generalists by nature, are not suitably trained for that kind of regulatory work, which is covered by dozens of engineering specialists and advisory bodies. Still, in this case, acting within existing legal codes was insufficient, and while this type of metal cladding was legally permissible, given its troubled history around the world, it might not have passed a sort of sniff test.

The more designers know about the materials they specify, the better. Architects are one component of a complex machine of players that gets a building built, and while they aren’t necessarily the final decision-makers, they are one of the few teams involved that oversees every step of the building process. From conception to execution, they have the potential to keep track of details that others may miss. Architects may not have been able to prevent the Grenfell Tower tragedy, but by agitating for safer regulations with the public’s best interest at heart, they can play a huge role in making sure that it does not happen again.

Header image via the New York Times