Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

COVID-19 leaps around the world, transmitted from person to person in close proximity. Though population density has not been the main determinant of viral spread (see Seoul, for example), in the US cities themselves have received much of the blame, prompting the rich to flee the restrictions placed on the multitudes who cannot leave.

Since the length of COVID’s stay and its long term health effects are not yet known it is certainly too early to objectively chart the cascading effects of pandemic and policy on our 21st-century cities. However, speculating on the direction and tenor of these lasting changes is unavoidable, and necessary. As we continue to quarantine, work from home, and avoid normal social interaction, we must turn our attention to the possible spatial consequences of COVID-related behaviors and policies sticking with us, even after the pandemic has passed.

The End of Innovation

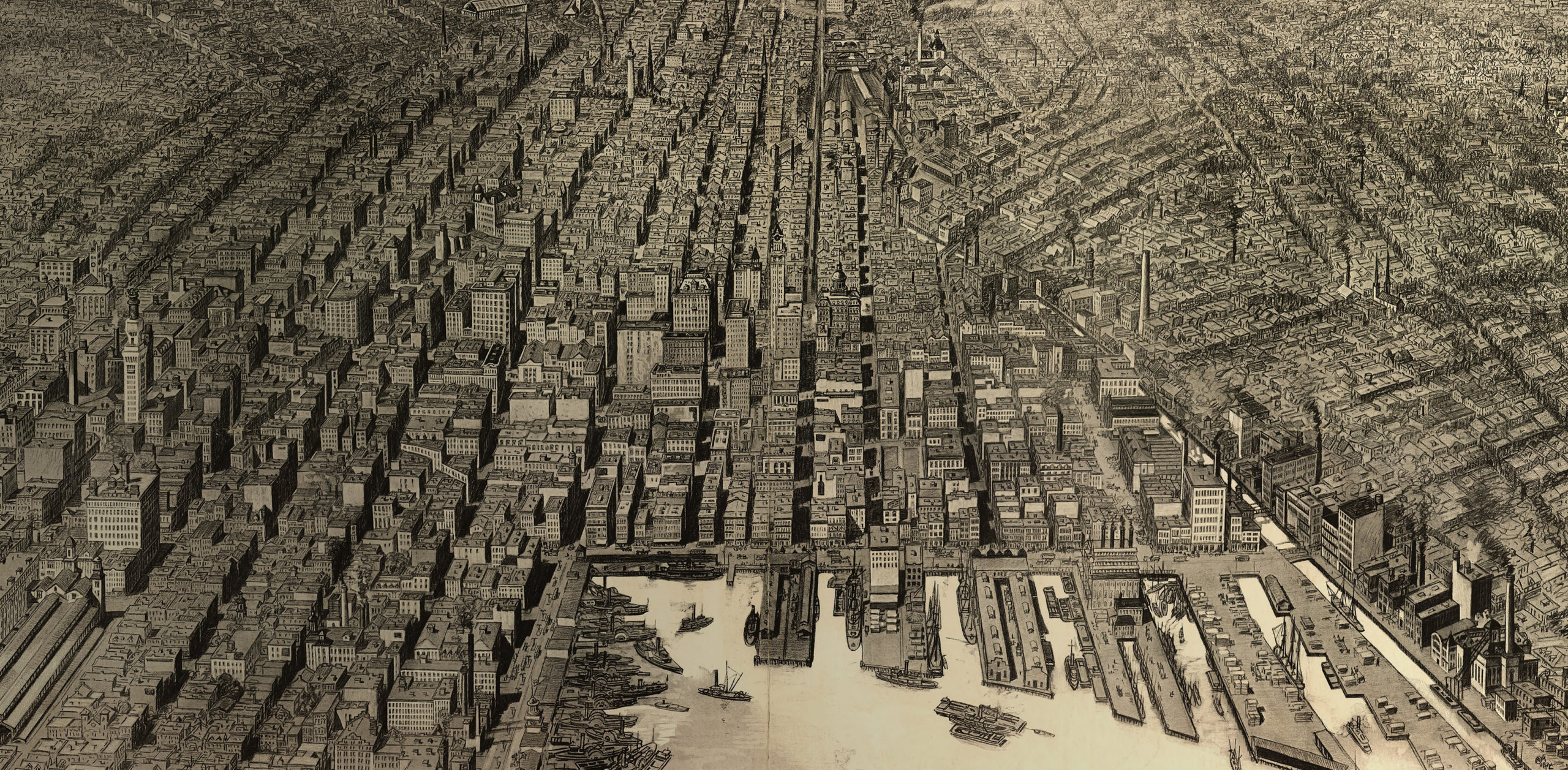

Cities are engines of innovation, their densities of people, resources, and institutions producing the random collisions and juxtapositions from which new technologies and ideas spring. Anti-COVID measures disrupt the physical proximity that cities thrive on in order to slow the virus’s spread, putting much of city life on hold until the pandemic runs its course. There is a real risk, however, of becoming accustomed to this lower-density way of life, especially if the pandemic continues for another year or more. And this lower-density way of life could, in turn, slow the pace of the random interactions that feed innovation.

Density is a prerequisite for progress and development in all its myriad forms. If working from home were to become the norm, what would replace the ad hoc water cooler or coffee run discussions that fuel collaborations across projects and between different roles? At architecture firms, the diminished capacity to ask quick questions or to observe other people working can seriously harm the cohesiveness of projects and even the ability to keep projects on track. Removing the daily ritual of commuting to work, as painful as it once seemed, can keep people from the random stimuli — seeing new buildings in the city, meeting strangers, smelling the wafting scents from food carts — that prompt new ideas and that precipitate memories but recontextualize them in space in time. And does Zoom really accommodate all the nuances of body language, side conversations, nudges, and napkin sketches from which new ideas emerge?

A city concentrates people and resources, with innovation emerging out of density.

Inequality and Segregation

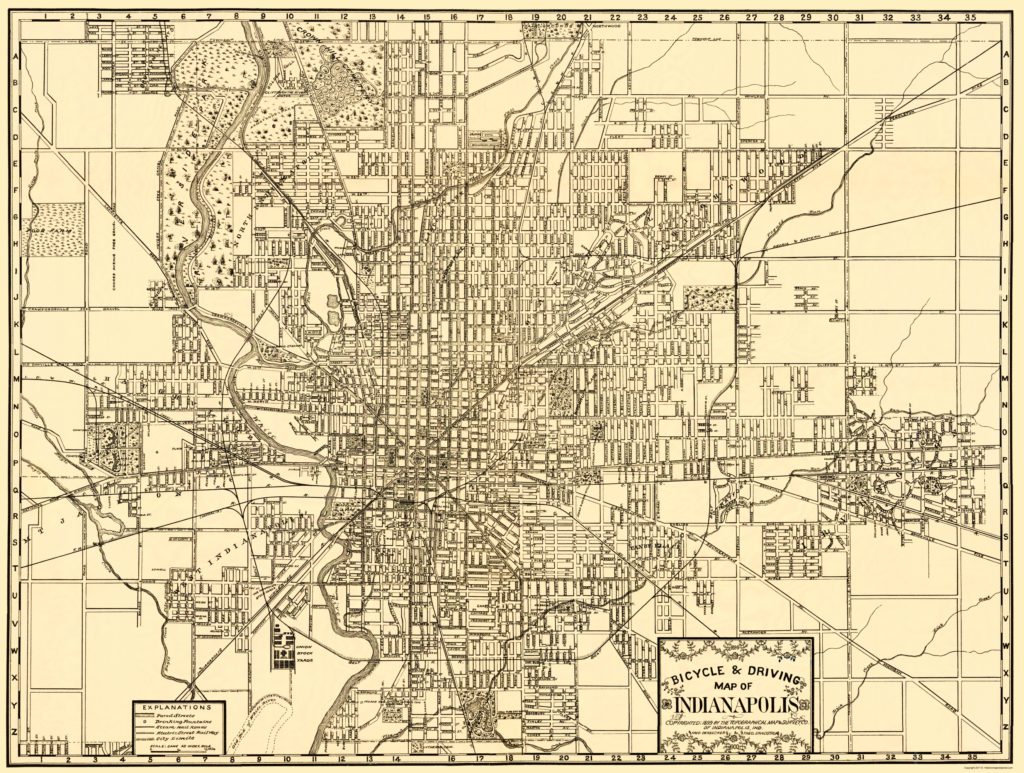

How will American downtowns fair if white-collar working from home continues? Specifically configured for corporate life, the value of these corporate-centric spaces will deflate and will become even more difficult to maintain or retrofit. Meanwhile, corporations will benefit from the diminished need to maintain office space. Companies can externalize much of their overhead by greatly reducing permanent offices.

Many firms covered employee costs for remote working during the pandemic, but if work-from-home becomes more popular (likely spun as a way toward increased work-life balance as an alibi for increased savings) then many corporations will likely begin putting the burden of equipment and space onto employees themselves. This includes office space, furniture, high-speed internet connections, phones, computers, and more. This will accelerate the growth of inequality between those who can afford to front the cost of all this and those who cannot; those who can easily find jobs and those who are doomed to repeating cycles of unemployment.

In terms of building typologies, a long-term move toward remote work would imply the need for larger houses and apartments. In the US, we’ve already seen a widespread trend of wealthier workers moving out to the suburbs or to rural areas during the pandemic, where large homes are perhaps cheaper and certainly more plentiful. This distorts the real estate market in the target jurisdictions, rendering home buying less accessible for locals and likely resulting in rent increases down the line as higher property values and taxes are passed on to renters. While getting out of the city is a short-term measure imposed by the pandemic, buying a house is anything but temporary.

In the cities which have been abandoned by higher-income workers, rents might fall for a time, especially in newly quiet neighborhoods. The pressures of gentrification similarly may be attenuated. But those who stay in cities could come to face new waves of disinvestment as social services and resources follow the wealthy back into the suburbs. Workers, especially in industries of care (nursing, daycare, etc.), may need to reverse-commute. The patterns of inequality once put into place during white flight in the 50s and 60s may again come to mark our cities.

In social terms, the increased spatial distance between income groups will again compound this country’s history of segregation based on race and class, decreasing the number of daily encounters between social groups and increasing the likelihood that again cities are disinvested of social resources and infrastructure —”out of sight, out of mind.”

Reversing Sustainability

This re-suburbanization — after a millennial renaissance for American cities — and the ensuing disinvestment from public infrastructure could possibly cause state and federal governments to repeat through inaction the gigantic mistake once perpetrated with racist motives: the incentivization of suburbia and car culture at the expense of public transit. As fewer people take public transit to work, these budget problems can only get worse, causing increasing problems with day-to-day issues including delays and malfunctions.

New York’s public transit infrastructure was struggling with funding shortfalls before the pandemic emptied its subway cars. Lasting skepticism of the safety of riding public transit by those who can afford other means will only deepen the financial strain. There will be many who still ride the subway — who depend on it even now — but administrative focus tends to shift as money does. This in turn can reinforce flight to suburbia and increase reliance on cars as a main mode of transportation. This in turn reproduces non-sustainable trends resulting from the last wave of suburbanization: over-reliance on fossil fuels, inefficient use of land, overuse of water and other resources, and time wasted in travel.

Waste can also be produced in the drive to retrofit city-center office buildings for other uses if remote work continues. Construction is a leading producer of waste material, as well as carbon emissions. Though tech firms could be easily accommodated, office buildings often are not easy to convert for residential uses — apartments and condos need shallower spaces to accommodate daylighting requirements, for instance.

Suburbia; image by Ryan Hagerty.

The End of Privacy

Security measures from the post-Patriot Act era show that once enacted, policies geared toward safety are hard to roll back. All 328 million Americans still have to take their shoes off at the airport, 19 years after the single failed attempt at shoe-bombing. Similarly, post-COVID, the innumerable tech-enhanced checkpoints on our daily routes — commuting, buying groceries, eating at a restaurant — may very well remain in place once the height of the pandemic has passed.

The tech associated with taking temperatures from a distance varies, but some versions rely on face recognition. As these technologies proliferate through cities, marking the entry to spaces of commerce, but also perhaps eventually to public spaces, it is important to figure out where this biometric data is being housed and for what ends. And future technologies promise more invasiveness — infrared cameras can be used to target individual protestors, for instance.

Similarly, the pandemic offered corporations the opportunity to enter the homes of their workers through productivity programs that track employee activity on their computers. This extension of managerial oversight into the private space of life and leisure seemed excessive during the immediate crisis of COVID-19, but as companies learn to more efficiently wield this software, this surveillance can only become more coercive and intrusive.

What if everywhere becomes a checkpoint? Image by TSA.

Anomie and Atomization

Considered together, the increased isolation and anxiety prompted by the pandemic has the propensity to have long-term public health impacts of their own. Social isolation, lack of movement, and loss of opportunity can lead to worsening health outcomes in the long term.

The increased economic inequality and the disparate impacts of working from home can only increase political and social fragmentation as people fall out of touch with other ways of life. Pre-pandemic America was already reeling from the pandemics of high income inequality, deaths of despair, and racist police violence. The changes wrought by the reaction to COVID-19 may increase the adverse effects of all of these preexisting conditions.

Levittown, New York; image by Acme Newsphotos.

The COVID-19 pandemic is a difficult challenge and cannot be taken lightly or wished away. But when it has run its course, or a vaccine has been successfully developed, there must be a concerted effort among local and federal levels of government as well as the private sector to rebuild the public realm and to prevent a relapse toward suburbanization and disinvestment.

There are signs of hope — the Black Lives Matter protests showed that cities are still places where people can come together to participate in politics and fight for justice. We must strengthen this function of our urban environments. Restoring our cities post-COVID is an opportunity to rebuild the public realm, on a stronger foundation of solidarity and social equity, with benefits to follow including better public health, innovation, and the ability to better address climate change.

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

Top image: Old map of Baltimore, via The City That Breeds