Architizer's new image-heavy daily newsletter, The Plug, is easy on the eyes, giving readers a quick jolt of inspiration to supercharge their days. Plug in to the latest design discussions by subscribing.

You have most likely heard countless references to the Metaverse over the course of the last year, and about how it is going to revolutionize our digital experiences like never before. Despite all the hype that paints the Metaverse as a single digital world that we can all visit, the reality is much closer to being a new way of using technology that adds a digital layer to our physical existence. The term describes a seamless way to move through interconnected virtual worlds to work, socialize, play and shop — all through a single device. Author Neal Stephenson is credited with coining the term in his 1992 science fiction novel Snow Crash, which envisioned lifelike avatars who met in realistic 3D buildings and other virtual reality environments.

The Metaverse is largely built on video-game engines, as a lot of the tools that power these digital environments have been used by game designers for decades (see Decentraland, The Sandbox or Cryptovoxels). These simulated environments allow for a spectrum of activities to take place, ranging from work to play and even e-commerce. If we are to spend increasing amounts of our time navigating through digital environments through augmented reality glasses or VR headsets, who should design these spaces and where does the architect’s role in this vision of the future lie?

Users visualize data on SpaceForm, a collaborative cloud-based platform. © SpaceForm Technologies Ltd

One of the benefits of the Metaverse is that it is not beholden to the laws, regulations or the very notion of gravity that governs our projects in the built environment. Often, these spaces are designed and coded by users or developers with little formal design experience. The comparable digital regulations are enforced by the designers of any given platform through its gaming code, which often results in a pixelated, blurry aesthetic that conjures up a certain nostalgia for earlier tech. While this space for play, exploration and the democratization of the designer should absolutely exist, how can the architecture and design community simultaneously harness the Metaverse to design more intelligently in the real world?

As creators with a firm grasp of the digital tools required to build complex and innovative projects, architects are uniquely qualified to engage with the design of the Metaverse. Typically, throughout the different stages of a project, architects produce a series of visualizations as the design develops to help communicate its intent. With the influx of newer technologies and design tools, these visualizations have evolved from static imagery to animations, immersive 360° renderings and even live simulations that allow a potential client to inhabit a project. It’s no surprise then, that global firms such as Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA) and Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG), and even some major cities have begun to make major inroads into Metaverse design.

Seoul Mayor Oh Se-hoon attends an event in the Metaverse, demonstrating the city’s plan to launch government services on the platform starting in 2022. © Seoul City Government

While there is certainly a strong desire to create innovative, gravity-defying designs within the Metaverse that far surpass what is possible in the real world, architects and designers would also be wise to use this space to test out concepts with real-world applications. It is abundantly clear that the gap between game design and architectural design is quickly shrinking.

According to Jensen Huang, the CEO of Nvidia, a company with a large stake in the evolution of digital environments, “the Metaverse is not hype.” At a recent conference, Huang elaborated on the concept of the Metaverse as a digital twin that will become indistinguishable from the real world. Simply defined, a digital twin is a virtual replica of a real-world design project, ranging in scale from handheld products up to an urban environment. It is typically composed of three key elements: visualization, forecasting and diagnostics.

If uploaded to the Metaverse, a project can be used to simulate real experiences, empowering both the designer and client with important data surrounding its experience. The company Buildmedia has even gone as far as building a complete digital twin of the city of Wellington, New Zealand, creating a platform for its citizens to better engage with urban data.

Users can visualize unbuilt infrastructure proposals in the Wellington Digital Twin model. © Buildmedia Limited

The pairing of digital replicas with physical environments or products also allows companies to run simulations using real-life scenarios before making costly decisions. So far, the biggest institutional adoption of the Metaverse and the digital twin has been from the art, shopping and entertainment industries; however, there are countless opportunities for the AEC industry. Whether optimizing the design of a retail environment to effectively situate products or maximizing the energy efficiency of a building, digital twins can have real world benefit outside of the Metaverse. The Digital Twin Unit, a collaboration between Scott Brownrigg Architects and Atlas Industries, formalizes this relationship by offering digital building and infrastructure analysis from the outset of a project. According to David Craig Weir-McCall, Head of Architecture at Epic Games:

“The Metaverse is this digital world that lives alongside our physical one and allows us to live, work and play alongside each other. And digital twins are the foundations that the Metaverse will be built on.”

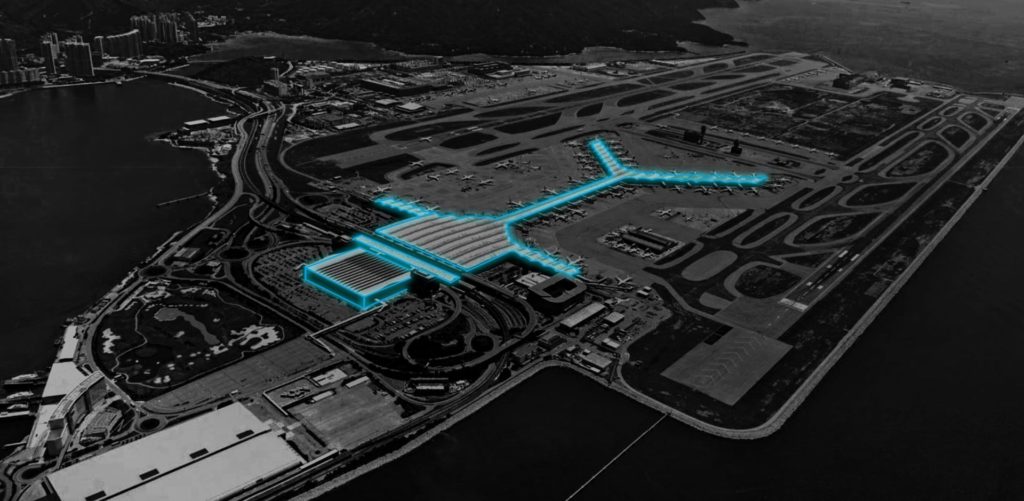

The Digital Twin Unit combines the design skills of architectural practice Scott Brownrigg and the digital technology expertise of Atlas Industries on projects such as the Hong Kong International Airport. © Digital Twin Unit

Another element of the Metaverse that has been rightly criticized is the large carbon footprint required to power the data centers it relies on. While this is a fundamental issue not only affecting the Metaverse, if more projects with real world applications are brought into this space, resulting energy efficiencies in the built environment will certainly help. Being able to build realistic virtual counterparts of buildings to simulate their environmental and experiential conditions could benefit scientific research and innovation. There is a great opportunity for architects and scientists alike to utilize this tech to help combat climate change and refine their projects, whether refining air conditioning distribution within the design of a building, or optimizing the location of solar panels to maximize light exposure.

For the moment, the Metaverse has been discussed primarily in terms of its experience and ability to immerse and impress a user within its world. But once we embrace and move past its aesthetic resolution and entertainment value, the Metaverse holds a great opportunity for the design community that could create a mutually beneficial relationship between both the physical and the digital world. At the end of the day, there is space for everyone’s vision of the Metaverse, and it might even help us expand design’s capabilities in the real world.

Architizer's new image-heavy daily newsletter, The Plug, is easy on the eyes, giving readers a quick jolt of inspiration to supercharge their days. Plug in to the latest design discussions by subscribing.