Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.

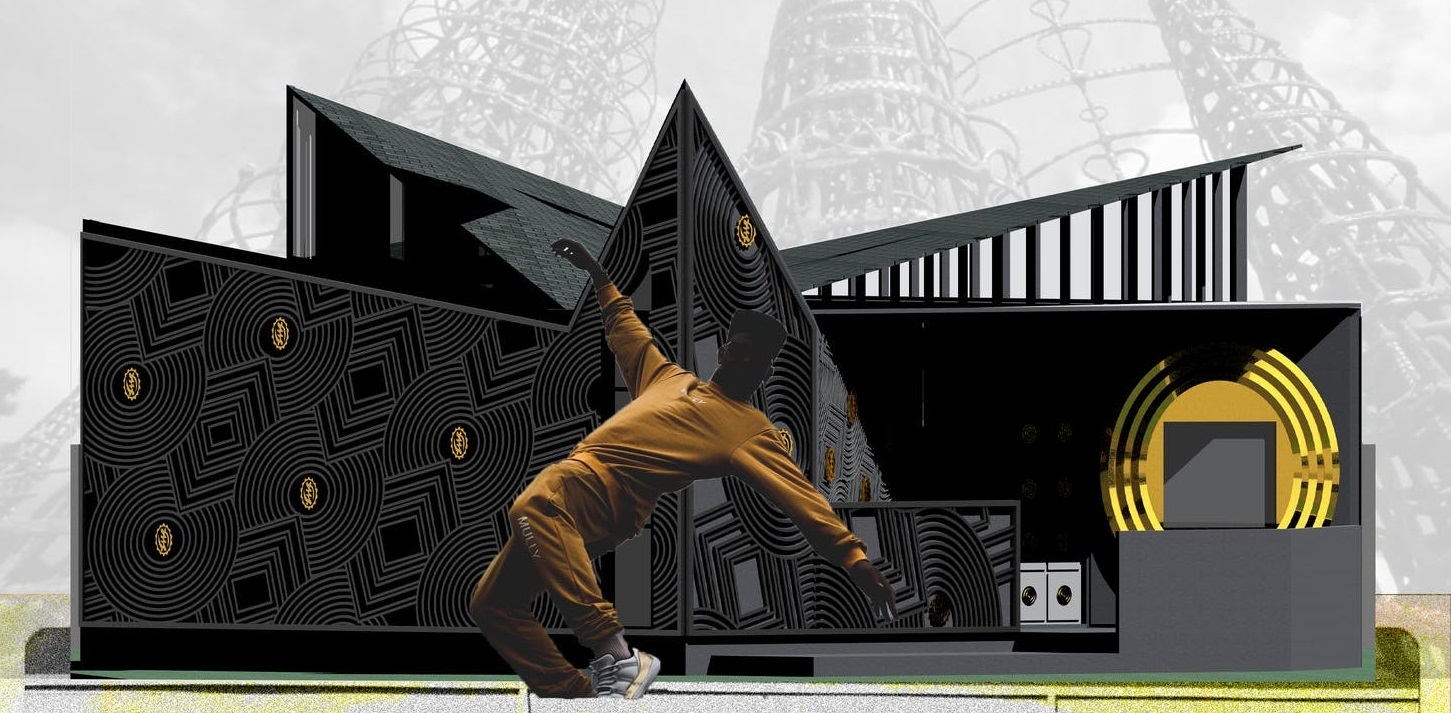

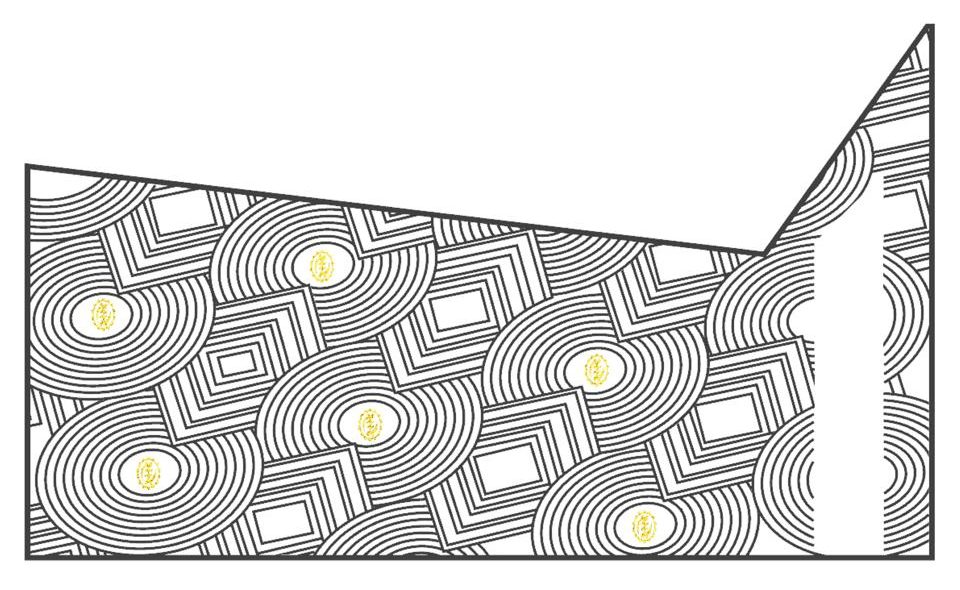

Demar Matthews is a designer rethinking the boundaries of architecture. He has been exploring Black architectural aesthetics in America through the design of a 700-square-foot Accessory Dwelling Unit (ADU) in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles. Through an initiative entitled “Unearthing the Black Aesthetic”, the project is intended to house designers participating in an artists’ residency, the project aims to elevate Black life and culture. His work focuses on building a Black aesthetic in architecture, as well as creating recognition and comfort in the built environment for Black Americans. With this first site, the project aims to not only create new expressions, but to amplify voices in the historic Black neighborhood.

As Demar notes, the Black Aesthetic explores global design, music, art, fashion and academia, addressing the past and future opportunities open to a diverse populace. It also presents Black culture as a unique framework in South Central Los Angeles. In this interview with Architizer, Demar explains his background and why he’s developing an architectural language derived from Black culture as he looks to the future.

Eric Baldwin: Why did you choose to study architecture?

Eric Baldwin: Why did you choose to study architecture?

Demar Matthews: I wasn’t aware of architecture as a profession until the end of undergrad. A couple years after graduating, I hated the field I was in, and I began searching for something else. I was always into different methods of expressing creativity, whether it was designing clothes, painting, drawing, building beds and desks, etc. (and then figuring how to make money off of it).

The need for a career change allowed me to look at different creative professions, but also how I could hustle and be an entrepreneur. After months of research and meditation, I couldn’t get architecture out of my mind and decided to give it a try. From there, I applied to Woodbury School of Architecture.

Can you tell us about how you started offTOP Design?

Can you tell us about how you started offTOP Design?

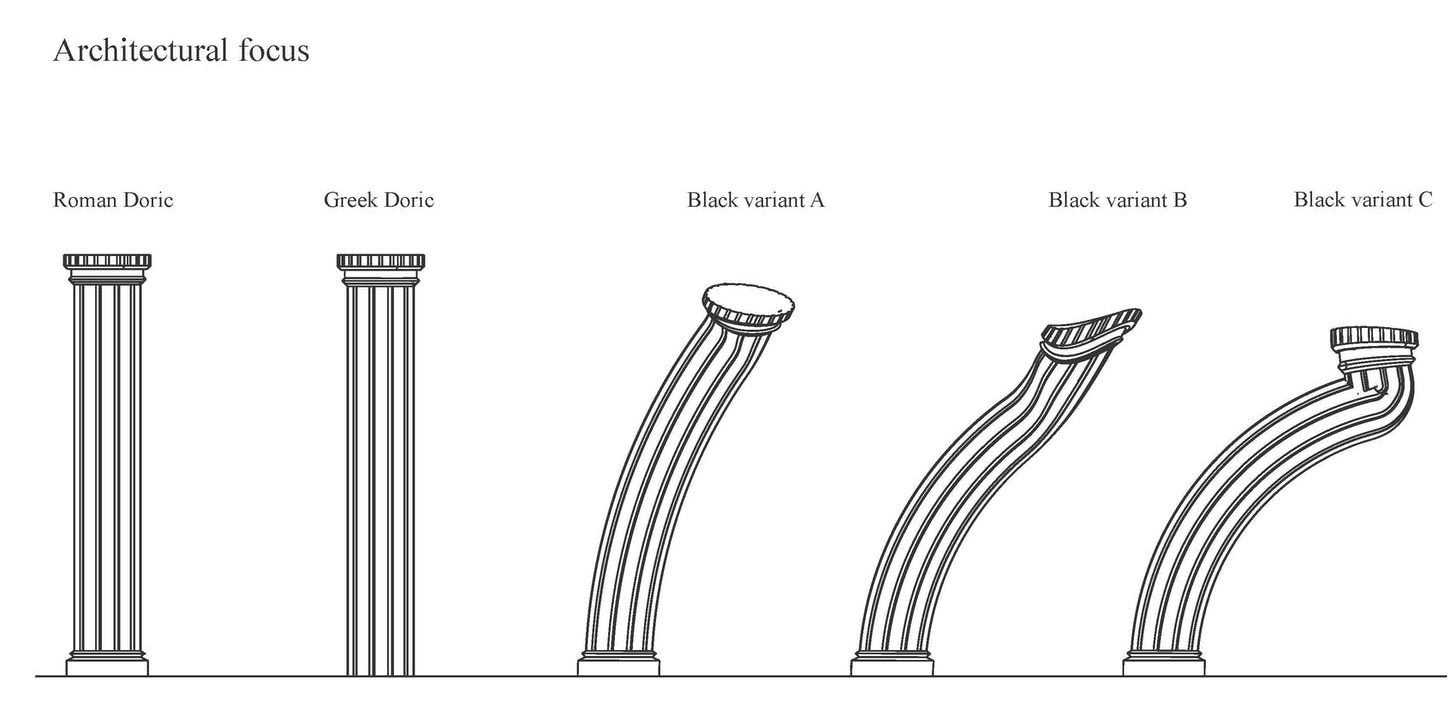

offTOP was conceived during my final year of school. Approaching thesis, I realized I had never been shown a precedent from a Black architect. I was also never shown architecture in Black communities. I felt I had only been given the tools to design other people’s communities, and through other peoples design aesthetics and beliefs of beauty. I didn’t see a place for me in architecture.

I decided I wanted to go into business for myself at that point, and focus on both the development of a Black Aesthetic in architecture and improving the built environment in Black neighborhoods through design. That is where the case study began, and how offTOP started.

“Unearthing a Black Aesthetic” is a case study consisting of homes that will be built in Black neighborhoods across the United States. You’ve already launched fundraising for the first one in Los Angeles; how do you hope this example will help elevate and celebrate Black life and culture?

“Unearthing a Black Aesthetic” is a case study consisting of homes that will be built in Black neighborhoods across the United States. You’ve already launched fundraising for the first one in Los Angeles; how do you hope this example will help elevate and celebrate Black life and culture?

So many cultures have their own architecture styles based on values, goals, morals, and customs shared by their society. When these cultures came to America, to keep their cultural values intact, they bought land and built in the image of their homelands. This isn’t necessarily true in historically black neighborhoods.

This project addresses the absence of Black aesthetic in architecture, celebrates Black culture/pride, and is based in Watts – home of the most dense population of African Americans west of the Mississippi. I hope this can be a method for designing against displacement. I hope it fosters the next generation of Black artists, architects, and entrepreneurs from L.A.

I hope black boys and black girls can look up at a building and see themselves reflected in it. Lastly, I hope it influences young designers to figure out how to create their own projects, and then get them funded and built.

offTOP explores the intersection of Black art, culture and experience through a range of programming. What advice would you give to other designers looking to foster change in their communities?

offTOP explores the intersection of Black art, culture and experience through a range of programming. What advice would you give to other designers looking to foster change in their communities?

Don’t be scared, be bold with your ideas. Collaborate with community non-profits/ organizations. If the community group does not exist, create it. Network as much as possible, and always follow up.

Changes due to COVID-19 have been swift. How do you think the pandemic will shape design?

Changes due to COVID-19 have been swift. How do you think the pandemic will shape design?

I think we’ll see a shift in the current business models that are common in architecture. I also believe small design studios and boutique firms have chances to impact design on a new scale like never before.

As you look to the future, are there any ideas you think should be front and center in the minds of architects and designers?

As you look to the future, are there any ideas you think should be front and center in the minds of architects and designers?

Personally, I am concerned with the ability to create my own projects and be sustainable. As a designer, it was a fear of mine that I would only be able to work if someone hired me. When we are lucky enough to get hired, we are fighting for our designs and concepts. I’m not interested in that model.

Partnering with a colleague and friend of mine from Lincoln University, Duane Gordon Jr. (Jet Design DC), we were able to acquire land, design a concept for a 6 unit multi family (using black aesthetics), and sell it to an investor. The money earned from that project is being used to acquire more land, and fund future projects.

All this to say, I believe if you have a critical practice, using entrepreneurship to fund it is of the utmost importance.

Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.