Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.

The images popularly associated with the French Revolution are often unpleasant. Hordes of sans culottes carrying severed heads on pikes; the sound of breaking glass echoing through the dark halls of the Tuileries Palace; and of course, the bloody spectacle of guillotine executions at the Place de la Concorde. I remember a tour guide in Paris telling me that, during the Reign of Terror, people wore galoshes in this part of the city because the streets were sticky with dried blood. I doubt this, but the story speaks to the ghoulish way the period is remembered.

No matter how many people worldwide celebrate Bastille Day by waving tricolors and donning berets, The French Revolution cannot shake its reputation of bloodthirstiness. Even sympathizers are quick to point out the revolution’s excesses. On the unsympathetic side, the political tradition we call conservatism literally emerged from Edmund Burke’s critique of the French Revolution, whose horrors he attributed to having gone too far, too fast.

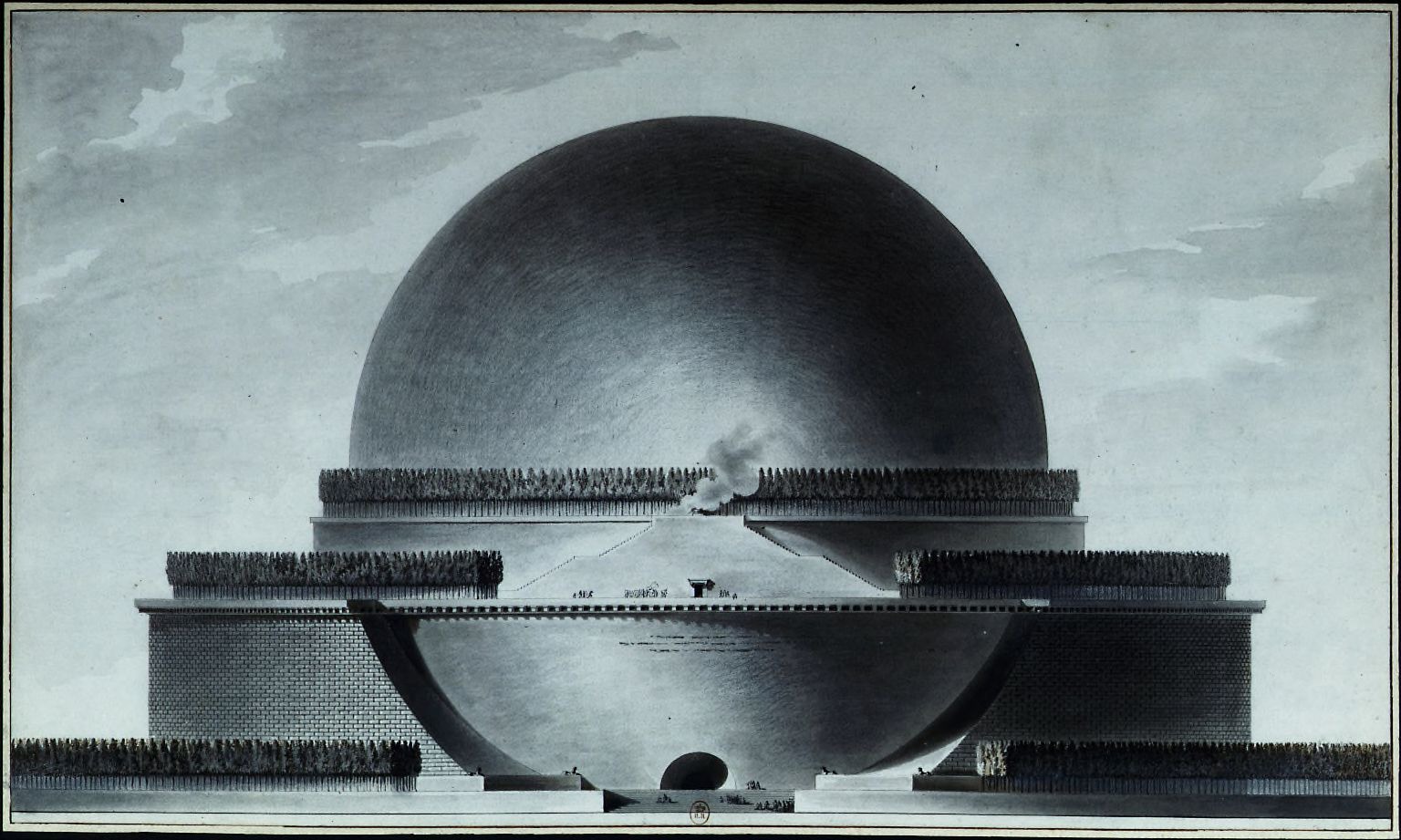

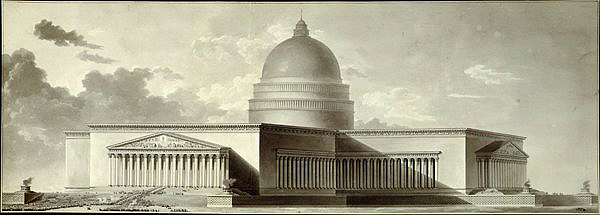

Étienne-Louis Boullée’s drawing of a church for the Cult of the Supreme Being, named Métropole. During the French Revolution, God was renamed “The Supreme Being.” Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Whatever one’s politics, it is hard to not be impressed by the sheer audacity of the Jacobins, who during the years of the First Republic attempted to change things as fundamental as the calendar. For a few brief years, 1792 was known as “Year One.” Even God was renamed. Henceforth, He was to be called the “Supreme Being.”

In art and architecture, as opposed to politics, the French Revolution’s legacy is more ambiguous. Although Robespierre’s rhetoric, with its calls for a radical renewal of the nation along secular and democratic lines, seemed to anticipate 20th century modernists like Le Corbusier, the most radical years of the revolution — 1792 to 1794 — saw very little construction in Paris, much less an upheaval of the city’s visual language. If there is one visual aesthetic that is closely linked to the French Revolution, it is Neoclassicism, which was also popular in the years before and after the revolution.

Jacques-Louis David is the painter associated most closely with the Revolutionary years due to his elegiac painting “The Death of Marat,” which has forever linked a serene and saintlike image with the man who encouraged the sans-culottes to “devour the palpitating hearts” of the bourgeoisie. But David was not really a radical in aesthetics; he was equally at home, a few years later, painting portraits of Napoleon.

One of the most enduring images of the French Revolution, Jacques-Louis David’s “The Death of Marat” depicts Jean-Paul Marat in the moments after he was murdered in his bathtub. Marat was killed by Charlotte Corday, a member of a rival revolutionary faction — not a monarchist — which complicates the idea that Marat was a martyr to the revolutionary cause. Corday objected to the bloodthirsty rhetoric of his popular newsletter, “L’Ami du peuple,” which celebrated atrocities such as the September Massacres. Marat’s complicated legacy is smoothed over by David’s serene composition. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

Nevertheless, despite David’s opportunism, there is something there — some aspect of his visual language that reflects the revolutionary spirit. Call it what you will — austere, Classicist, boring — this sensibility was a definite break from the Baroque and Rococo styles that predominated in the 17th and 18th centuries in both painting and architecture.

In its clarity and restraint, Neoclassicist art and architecture offers an implicit critique of decadence. It promises renewal through a return to fundamentals. As Victor Hugo put it in his 1874 novel Ninety-Three, the aesthetic of the Jacobins was all about “hard rectilinear angles, cold and cutting as steel . . . something like Boucher guillotined by David.” And the French Revolution wasn’t alone in favoring a hard and clarifying style. This was also true of subsequent revolutions — revolutions of all kinds. “Rip it Up and Start Again” is not just the title of a post-punk song, but a summary of the punk ethos. And punk is certainly the most Jacobin of rock sub-genres.

If Neoclassicism and punk seem like strange bedfellows, consider the phrases commonly linked with the punk sound. “Stripped down,” “raw,” and even “back to basics.” One could add “back to nature.” There was a Rousseauist quality to punk rock, a nostalgia for a romanticized past thought to be more authentic than the decadent present. Disco was like Rococo architecture in this analogy. Overwrought, decorative — and implicitly feminine. Punks believed it should be guillotined.

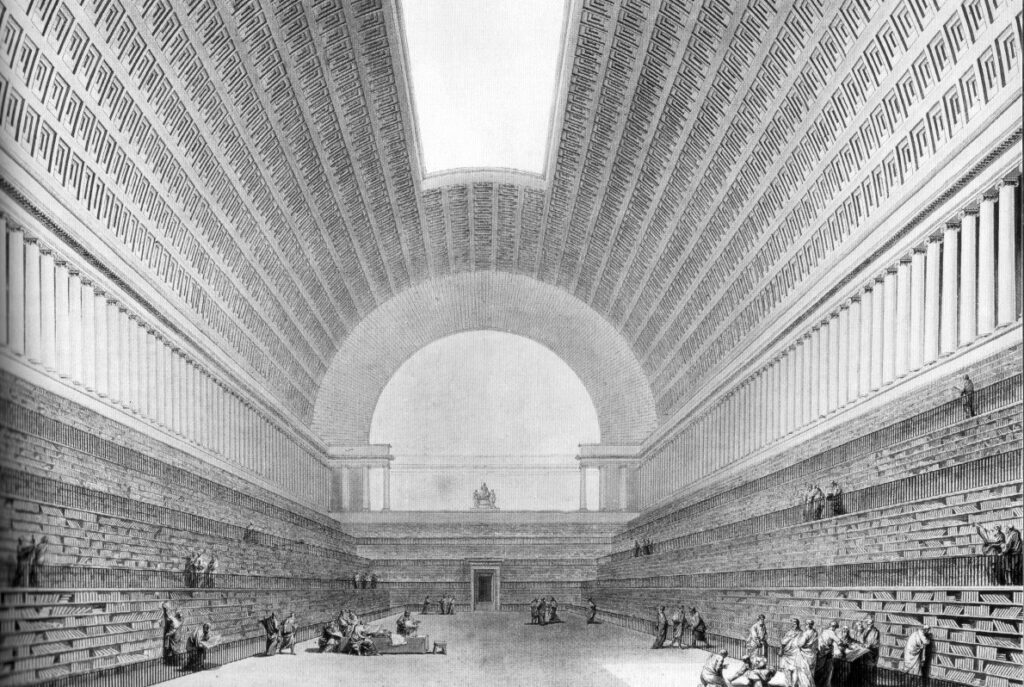

Étienne-Louis Boullée’s design for a national library. Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

It is in aesthetics where one can see the totalitarian seeds lurking within the revolutionary flower. In particular, there is danger in the revolutionary drive toward purity. We can see this vividly in the designs of Étienne-Louis Boullée, the only architect of the period who seriously attempted to embody revolutionary ideas in architecture.

Boullée was born in Paris in 1728. He had a traditional education, and while studying under major French architects witnessed firsthand the shift from French Classical architecture to the more austere Neoclassical style. This evolution in taste coincided with a debate over the status of architecture. A popular view of the time held that architecture was not really an art form because its purpose was to serve a social function rather than to imitate nature. It was in response to this opinion that Boullée wrote his treatise “Architecture, Essay on Art,” which was not published until 1953.

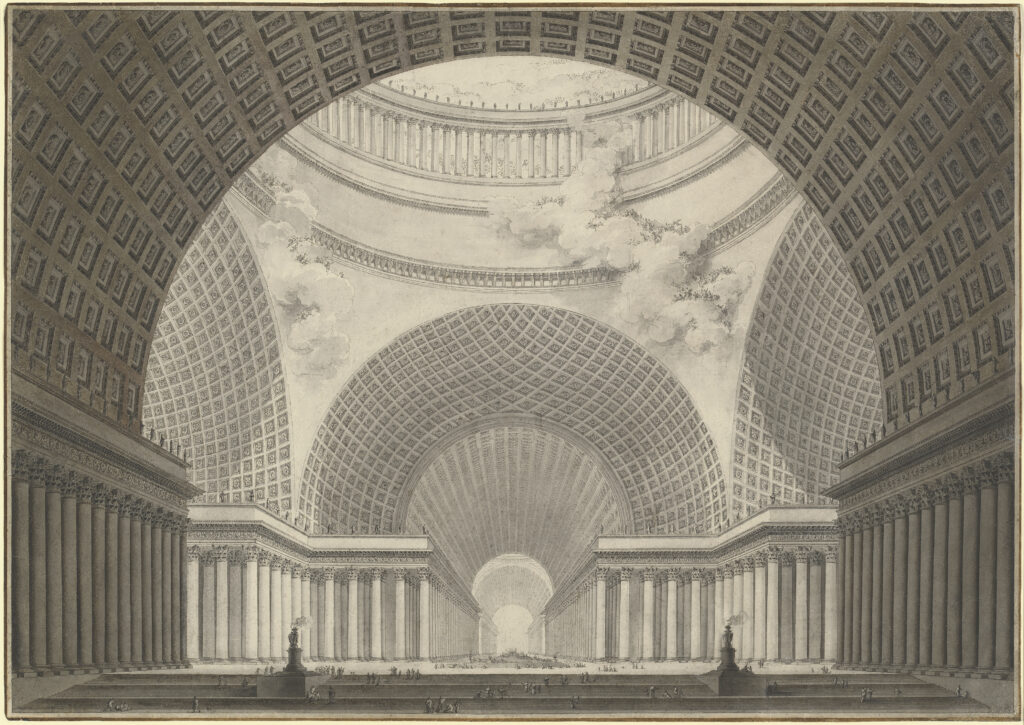

Etienne-Louis Boullée (French, 1728 – 1799), Perspective View of the Interior of a Metropolitan Church, 1780/1781, pen and black ink with gray and brown wash over graphite on laid paper, with framing line in brown chalk, Patrons’ Permanent Fund 1991.185. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

In this essay, Boullée argues that architecture could realize itself as a major art form once architects began to consider not only the function of their designs, but their expressive significance. “To give a building character,” his essay reads, “is to make judicial use of every means of producing no other sensation than those related to the subject.” His favorite example was the Egyptian pyramids, which meet their funerary purpose by “conjur[ing] up the melancholy image of arid mountains and immutability.”

They key assertion Boullée makes in this essay is that each building should have one expressive purpose. Elements that do not fit the vision must be excluded. The plans that he created to illustrate this point are certainly impressive. Take his Cenotaph for Isaac Newton, which is shaped like a giant sphere because Newton’s law of gravity “defined the shape of the earth.” Or his Palace of Justice, designed during the revolution, which was to contain the parliamentary courts, excise boards, and audit offices. These municipal structures rest atop a small prison, a “metaphorical image of Vice overwhelmed by the weight of Justice.”

Boullee’s “Cenotaph for Isaac Newton.” This cutaway illustration shows what the monument would look like at night. Boullee envisioned that light conditions would be inverted: during the day, the interior would be dark, and at night it would be illuminated by a suspended spherical lamp. Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons.

The monolithic grandeur of Boullée’s designs today seems more dystopian than revolutionary. Individual humans are dwarfed by these designs, which seem to express one idea above all: power.

I think Boullée’s drawings tell us something about the dark side of revolution. Lurking underneath the noble desire to destroy injustice is a deep uncertainty about what comes next. What will the world look like once it is purged of everything that is messy, improvisatory and corrupt? The revolutionary must envision a new ideal, but ideals are famously cold, distant and lifeless. Perhaps it isn’t a coincidence that Boullée’s favorite typology was funerary monuments.

Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.

Cover Image: Étienne-Louis Boullée, Cenotaph for Isaac Newton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons