Wandile Mthiyane is an Obama Leader, TedxFellow, architectural designer, social entrepreneur and the founder and CEO of Ubuntu Design Group (UDG) and The Anti-Racist Hotdog. He is proud to introduce The Tea, a peer-to-peer inclusion rating platform.

“Hey bro, look at where I spent Christmas,” I bragged as I sent my friend a picture of my family home in the Eastern Cape. I intentionally withheld the fact that I was the designer of this home.

He swiftly responded, “Bro, that looks like the home my ancestors grew up picking cotton on.” My knee-jerk defensive reaction was to text, “Well, like the N-word, I have reclaimed this style for my Black family.” As I wrote those words, however, I wondered if I truly had reclaimed this style.

Can we remember, acknowledge and reclaim — or even indulge in — architecture that, to certain marginalized groups, represents oppression? Can we do so without sanitizing my family home to look acceptable to my critics of neoclassical architecture because of its symbolic association with slavery?

This is the question I’ve been asking myself since the day I was asked, at age 26, to design the house that would replace my mom’s childhood home, effectively becoming the central home for my maternal side. As I write this article as a 30-year-old man, four years later, my perception and perspective on this topic — regarding race, equity and reparations — have drastically evolved. I began thinking about the racial implications of the house’s style from the moment that my uncle requested it. The examples they sent me were of classical, colonial-looking architecture instead of a more traditional African aesthetic, which I would have preferred.

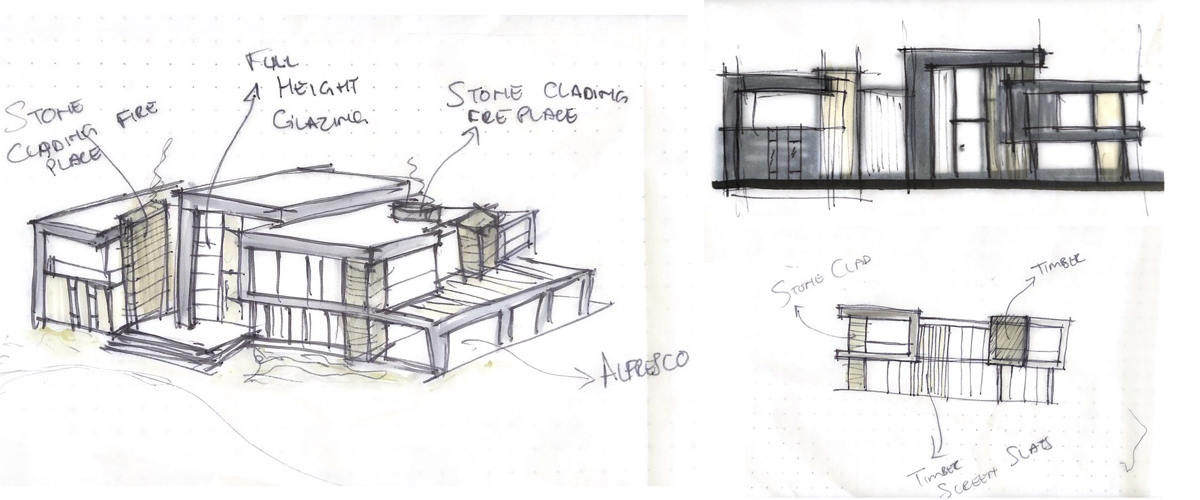

Early sketches, by the author, revealing how he initially imagined the project with a very contemporary scheme.

As an anti-racist architecture advocate known for affordable housing and reimagining African architecture, I reflected: “Am I selling out for taking on this project? But then again, I’m 26; who else will trust me with another 20 million-rand mansion? Am I selling out for designing this home for my family in post-apartheid South Africa?”

During this time, I also started an inclusion consultancy called the Anti-Racist Hot Dog to explore ways we can build bridges across differences in our workplaces, schools and communities. This journey has moved me away from binary thinking, where classical architecture is categorically “bad” and traditional African is “good.” It encouraged me to understand other people’s perspectives and ask questions about why they prefer one style over another. I now want to honor people’s experiences because people’s experiences shape their perception of a style. All those experiences matter.

A significant part of this exploration of the tension surrounding the architectural style of my home comes from spending Christmases there, creating new memories. As I spend more time at the house, I fall more in love with it because of those memories. Does this then mean that, if we expose Black people to this type of architecture and luxury in homes, there could be a shift from them representing oppression to being owned by Black people? It becomes an architecture they own, not where they are picking cotton. My goal is that the memory of this house and its style will represent family, Black love and freedom to my cousins, nieces and future generations instead of what it currently symbolizes to many in my generation.

As criticism and admiration pour in for this home from my friends and strangers, I can’t forget what Viola Davis once said: “Critics think they’re telling you things you don’t already know.” But the truth is that no one knows the physical and ideological mistakes of their design work better than its creator.

The constructed home designed by the author for his family in collaboration with his design team, Mona-Lisa Mthethwa, Nontokozo Mhlungu, Ngoako Rangwato, Tino Mkhumbareza and Mbuso Msipho.

When my uncles first approached me with this project, I threw a fit, took them through a historical lecture on why it’s a bad idea for us to build a home in an architectural style that was used by our oppressors, and how instead we should be the patrons that set an example of what African luxury architecture looks like.

To all of this, my uncles responded, “Mtshana, when you have your own money, design and build an African architecture home, but as for us and our household, this is what we want.”

This statement took me aback. In the culture where I grew up, you cannot tell elders what to do or how to think without being disrespectful, so I knew this was effectively the end of the discussion. All I was left with were my thoughts.

So, this made me think about why this style was so important to my uncles. After some time, I remembered that when they were growing up as kids during apartheid, Cape Dutch homes or Victorian mansions were symbols of success. I can almost imagine their conversations as they walked several kilometers to school. Looking at the homes they walked past, they would tell each other that one day, they too would live in a home just like the racist white farm owners lived in.

In some ways, it was a symbol of protest. In other ways, it was a symbol of luxury because that’s the only form of luxury and success that was modeled to them. Then, some twenty years later, a self-righteous kid they put through architecture school comes and tells them that their preference is a result of self-hate, and they should be more African in their taste.

Which brings me to the elephant in the room: What’s the role of an architect in the design process? Are we meant to “listen to build”? Is the client always right? Do we exist to execute the dream of our client, or are we there to advise them on alternatives? What if they don’t take our suggested alternatives? Do we continue to execute their dreams, or do we quit? Is part of our job description design righteousness?

Details of the home that the author designed for the site of his mother’s childhood home in collaboration with his design team, Mona-Lisa Mthethwa, Nontokozo Mhlungu, Ngoako Rangwato, Tino Mkhumbareza and Mbuso Msipho.

This conversation is especially interesting to me because when I show this home to my friends and Instagram strangers who aren’t in the architecture fraternity, their first response is, “When can they visit?” They say the house represents luxury, “soft life,” and looks like a palace.

But when I show it to my millennial architecture peers, the response is surprisingly split. When I showed them the design, most of them judged me and said, “Why am I designing a colonial house in South Africa?” When I showed them the finished home, half of them converted and asked when they could come visit and were in awe at its grandeur. The other half pointed out the references to slavery yet still implied that they’d love to come see it.

This made me realize that the closer we are to studying architecture, the more likely we are to see, reflect on, and care more about the symbolism of architectural style. While the symbolism isn’t lost in the eyes of the general public, they seem to somehow be at better ease at seeing and enjoying the luxury and the benefit of the style versus being hindered by its obvious past.

Historically, classical architecture and its offshoots weren’t always associated with the slavery of Black people nor colonization. In fact, classical architecture draws its roots from Mesopotamian and Egyptian architecture, which makes the argument that the style, in and of itself, isn’t racist. However, in traditionalist dialogue, the African and Mesopotamian roots of the style are often erased or overlooked. This style has represented many different things to many people, from freedom, innovation, renaissance and civics to slavery and colonization.

The custodians of this architectural style haven’t always been the best people in history. In fact, many of them are responsible for the underdevelopment of African architecture and other indigenous architectural languages around the world, which they demonized and called barbaric.

Entrance to the home that the author designed for the site of his mother’s childhood home in collaboration with his design team, Mona-Lisa Mthethwa, Nontokozo Mhlungu, Ngoako Rangwato, Tino Mkhumbareza and Mbuso Msipho.

A recent example of this style being used in an authoritarian way was in February 2021 when President Trump came up with the “Make Federal Buildings Beautiful Again” mandate, requiring the use of “traditional” architecture in the construction of all new federal buildings. The order defined “classical” as including Neoclassical, Georgian, Greek Revival, Gothic, and other traditional styles, effectively outlawing any other architectural style. President Trump called everything else “undistinguished,” “uninspiring,” and “just plain ugly.”

Decrees like this stifle Indigenous design explorations and create a hierarchy of importance, suggesting that one civilization or people group is more important than another, subtly disseminating this message through style and representation. As Churchill noted, “We shape our buildings; thereafter they shape us.” If there’s only one acceptable style, what kind of society are we shaping?

Meanwhile, this is a style marred with oppression, even from its European roots. Some of its biggest vessels were churches, buildings which were often built using poor people’s last money with the promise of salvation, religious manipulation, and indentured servitude. On the contrary, classical architecture is a masterpiece in the value of cumulative knowledge. Different eras of this style have added to its timelessness and its ability to be useful, adaptable in use with time, and durable across centuries.

As the architecture theorist David Watkin argued 40 years ago, promoting or denigrating a style “on supposedly ethical grounds” confounds “moral principle [and] aesthetic preference.” There is nothing intrinsically racist about, say, antebellum architecture, and nothing inherently freedom-like about the Cradle of Humankind building in South Africa. However, these two types of buildings still represent something to people: oppression and liberation, respectively.

While I agree with David’s principle, in reality, these buildings mean something to us. This is why it’s important to be intentional about representation, telling the full story of a style’s origins and reshaping the narrative by reclaiming styles — a form of redemption for those who once picked cotton within their walls.

So, what do you think: can we reclaim classical architecture for Black and Brown people?

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.