The judging process for Architizer's 12th Annual A+Awards is now away. Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter to receive updates about Public Voting, and stay tuned for winners announcements later this spring.

Despite all the talks around inclusivity and diversity in all aspects of life, the idea of universal design is still not one that is widespread. The term, first coined by American architect Ronald Mace, and then later popularized by architect Selwyn Goldsmith, explores a branch of design that caters to everyone regardless of their age and abilities. This implies going beyond wheelchair-accessible spaces and addressing the vast spectrum of disabilities that can exist.

The limitations of designed environments first became a topic of discussion after the second World War when we saw a large number of injured veterans. While the advancement in medicine made it possible for them to live longer lives, there wasn’t enough infrastructure that was entirely accessible to them. Veterans in the United States demanded equal rights for themselves, leading to the establishment of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990.

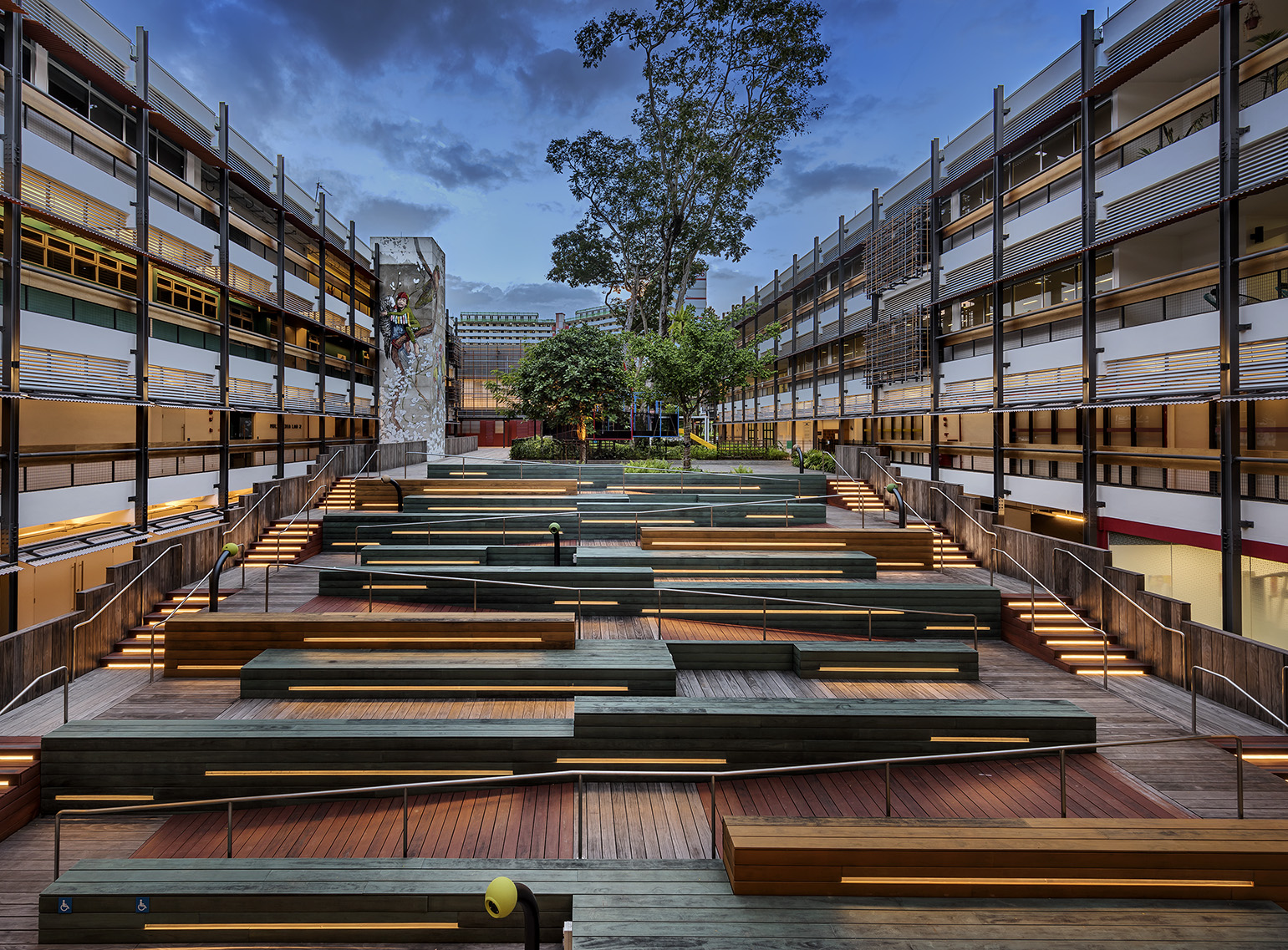

Enabling Village by WOHA in Singapore | Photo by Edward Hendricks

But having equal rights was not enough. When it came to spaces and environments, Mace was instrumental in creating the seven principles of Universal Design in 1997. These are equitable use, flexibility in use, simple and innovative use, perceptible information, tolerance for error, low physical effort and size and space for approach. They are meant to serve as guidelines for designers to create more inclusive and accessible environments.

Equitable use implies the provision of the same degree of access, security and safety for all users. The principles also point to flexibility by accommodating a wide range of preferences such as left and right-handed access, provision for different paces of movement and so on. They also state that the design should be intuitive in a way that individuals with different literacy and language skills should be able to navigate the space without any difficulties. The information provided should also be presented in graphic, audible and tactile forms. Each space must have warnings of hazards and errors and preferably have these high-risk elements isolated. Transparency in buildings, recurring seating spaces, anti-skid surfaces, tactile floor guides and handrails with easy grips are just a few other examples of elements that can be included.

Enabling Village by WOHA in Singapore | Photo by Edward Hendricks

According to Indian architect and Universal Design advocate Kavita Murugkar, Universal Design is an almost fundamental value given that it ties in with accessibility and, in turn, an individual’s right to freedom. She said, “Everyone is talking about equality and extending equal rights and opportunities for all individuals, and creating equal possibilities of participation in the society. This is possible only through equal means of access.”

While we have come a long way in our understanding of what design needs to do, there is still a slightly limited perspective of disability while designing. The needs of someone who is an amputee might be very different from someone who is visually impaired. The latter might need many more tactile and audible cues to guide them in spaces whereas an amputee could require some more room to accommodate any aids they might have.

Enabling Village by WOHA in Singapore | Photo by Edward Hendricks

Furthermore, someone with missing arms could require alternative ways to use buttons or even open doors. An individual with Parkinson’s might need spaces that have finishes and interventions that are favorable for those who struggle with balance. And that is just on the physical level. People with autism might require quiet rooms and those with dementia could benefit from surroundings that have fewer identical elements.

A project that has tried to address this is the Enabling Village in Singapore. Designed by WOHA, the community space offers retail, recreational and training services for differently abled individuals. All public spaces and restrooms in the building are wheelchair accessible. The event spaces have induction loops that can transmit audio to people using hearing aids with T-coils and they also provide braille maps of the space if needed. Even elements like ATM machines in the center have braille labels and earphone ports. The project includes a center for innovators to gather and test ideas for assistive technology. It is equipped with a room where these inventors can also test their products in fully soundproof and lightproof spaces. Furthermore, they are also creating job opportunities for the differently abled members of the community.

Friendship Park (Parque de la amistad) by Marcelo Roux, Gaston Cuna, Patricia Roland and Federico Lezama, Montevideo, Uruguay | Photos via issuu.com

Another example of inclusive design is the Friendship Park in Montevideo, Uruguay that is designed by Marcelo Roux, Gaston Cuna, Patricia Roland and Federico Lezama. It is made in a way that children of all ages can enjoy the space regardless of their physical or cognitive abilities. Apart from the easily accessible spatial arrangement, materials like concrete, metal and rubber are used in abundance to provide tactile and aromatic cues to the users. The team has tried to incorporate more curved surfaces to avoid sharp edges; they have also used a variety of colors throughout to make it appear more fun and the spaces easy to recognize and remember.

Murugkar said the awareness about Universal Design is still not as much as it should be, especially considering its importance. She introduced it as an elective in Dr. B. N. College of Architecture in Pune, where she is an Associate Professor. But she believes that we need to get to a point where the subject is integrated into the entire curriculum and not just taught as a specialization. “Universal Design is a utopian idea. You can definitely not have a design that addresses the needs of every single individual on this earth,” she said. “It just aims to make the spectrum of usability of a particular service or product or an environment broader and broader.”

Inclusive design is more of a way of approach than a design methodology that must be implemented right from the conceptual stage and carried through to the smallest element in the final product. While this approach may give rise to innovation, the question remains: is actually possible to cater to every individual and make this philosophy a reality?

The judging process for Architizer's 12th Annual A+Awards is now away. Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter to receive updates about Public Voting, and stay tuned for winners announcements later this spring.

Enabling Village

Enabling Village