Architizer's 13th A+Awards features a suite of sustainability-focused categories recognizing designers that are building a greener industry — and a better future. Start your entry to receive global recognition for your work!

Gaze out at any urban environment today, and one thing is almost always true; a collection of tower cranes dots the horizon line. These cranes are the vehicles that facilitate a constantly shifting skyline as buildings are systematically demolished and erected to keep up with the never-ending demand for new real estate, whether it be commercial or residential. However, in densely populated urban environments, there are rarely vacant plots to erect these projects; the existing structures must first be demolished to make way for what is to come.

This ritual of demolition and construction, whether at the scale of an entire building or an interior renovation, perpetuates a cycle of unsustainable material renewal that heavily contributes to the built environment’s carbon emissions — up to 50% of the annual global total. While we commonly think of steel, glass and concrete as the primary culprits, recent research has shown that the relatively rapid pace at which we renovate and update our interior environments may be responsible for a level of emissions similar to those associated with the structure and envelope of a building.

In addition, when you construct a building, adding new material fundamentally means that you are subtracting from somewhere else, thereby sustaining the material economies of extraction sites. Both the additive and subtractive elements of construction and deconstruction need to be considered with equal weight for the obvious reason that our earth contains finite resources we continue to exploit.

The materials and products in an office environment are systematically removed. © Rotor

With this in mind, a series of cooperative design practices across Europe have made it their mission to rethink the organization and life cycle of the material environment, in an effort to salvage and re-use materials wherever possible in projects both small and large. Collectives like the Brussels based Rotor and its spin-off, Rotor Deconstruction, along with Materiuum in Switzerland, offer to do the delicate dirty work that many companies will not. That is, to systematically and surgically remove and reclaim the materials that make up an existing architectural project before it is demolished or renovated.

Finding the right materials — those that make sense to dismantle — is often a delicate balance of the cost of labor and the material’s secondary resale value, not to mention finding time in an on-going construction project’s schedule. By trading in salvaged materials, Rotor helps to reduce the quantity of demolition waste in any given architectural project, while subsequently offering quality building materials that have a negligible environmental impact. Many of the sourced materials are actually cheaper than new inventory and have the same quality. In other situations, materials can be as expensive as new stock, but are salvaged and re-installed with a deep patina and the knowledge of their prior origins, which makes for a clear conscience.

Salvaged materials waiting to be employed in other building projects. © Rotor

One of the main challenges of Rotor’s work is also undeniably the skill and care required to systematically salvage materials. Toilets or other fixtures are one thing, but intricately installed encaustic cement tile flooring or tongue and groove wood siding requires a delicate hand that can take time out of a busy construction schedule. It’s worth noting, that their work requires proper permitting for demolition and a much more sensitive attitude towards this phase of the project.

Moreover, once materials or fixtures are removed from the construction site in question, they must be stored and cataloged before they find a second life in another project. Sometimes materials are already spoken for when salvaged from a project site, but they can often spend weeks or months in limbo as they wait for architects to specify them for another project.

Ceramic tiles are carefully removed by hand. © Rotor

In addition, when a developer considers the cost of demolishing a large building in an urban context, the cost to the local context and society is rarely considered. As large trucks cart demolished material through the streets, increasing noise and air pollution within the environment, there is an unquestionable effect on the surrounding businesses and quality of life. All of these costs need to be included in the bottom line of a company looking to build anew on a site which may afford opportunities with what is already there.

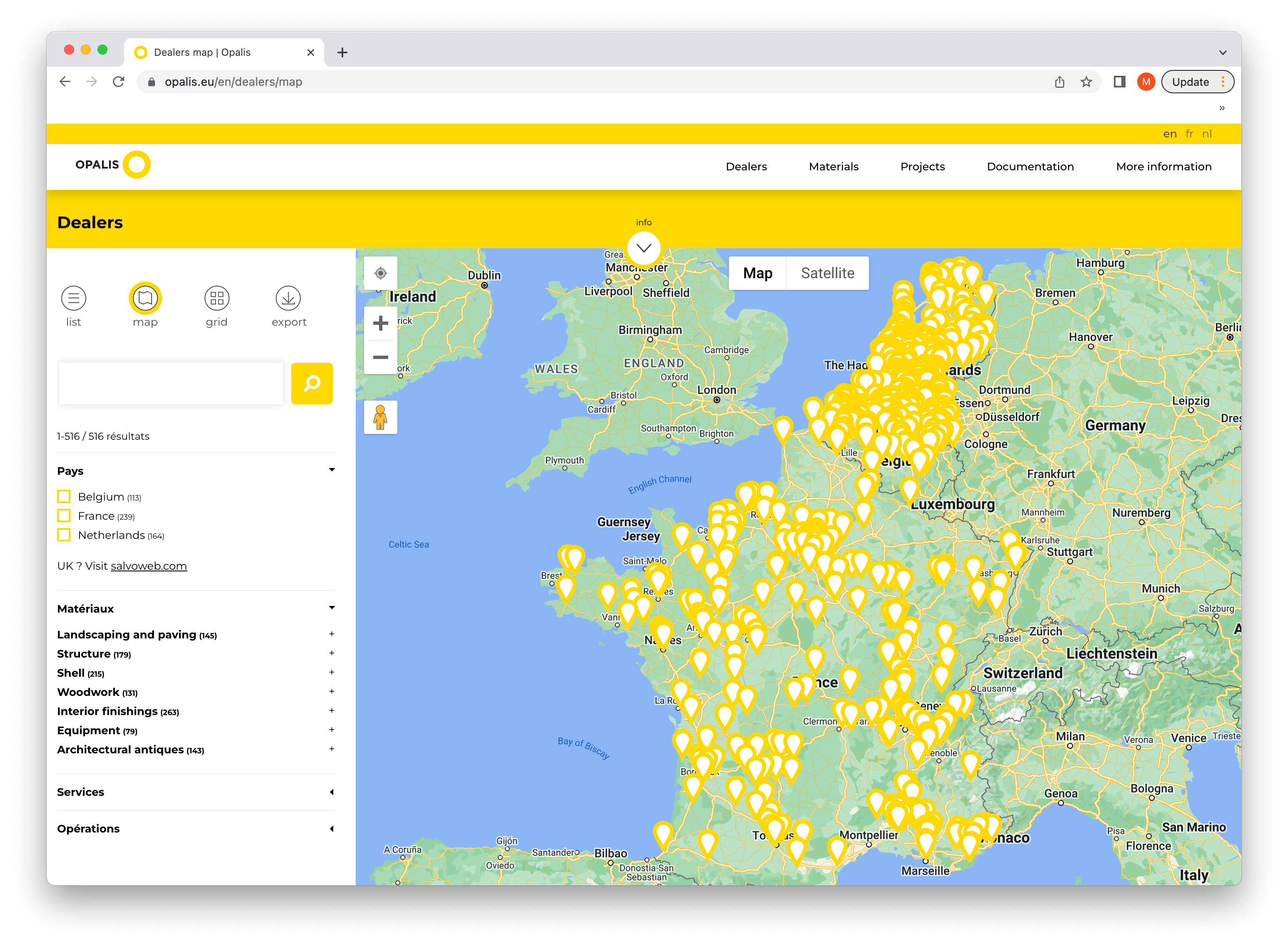

A map displaying salvaged material dealers across Europe. Image courtesy of Rotor’s Opalis

A fundamental challenge that exists in this work is the development of the infrastructure to enable reuse at scale. To tackle this, Rotor has worked to develop Opalis, an online resource developed with European funding that seeks to create a widespread knowledge map of the salvage industry at large. This visibility allows the cooperative to tackle issues associated with the reuse of a specific material, so that they can better understand how to facilitate its use in projects.

Architectural products and materials lie in wait. © Rotor

As anyone who has worked on a renovation or adaptive-reuse project can attest to, working from existing built conditions can provide a whole host of surprises, both good and bad. Any given day, the removal of sheetrock could reveal a hand-painted fresco or custom mosaic wall, while it’s also common to find a host of issues and damage related to the age of the materials or building systems in question.

On a certain level, collectives such as Rotor, Rotor DC and Materiuum are employed as retrofit and deconstruction consultants, to study what is possible to create, remove or reuse both structurally and financially. Depending on the scale of the project, they may work as designers, consultants or laborers, flexibly adapting to the best outcomes that the project presents.

Rotor’s warehouse and showroom. © Rotor

There is an interesting double standard that exists when it comes to assessing aging buildings and their materials. On the one hand, we celebrate the well-worn patina of materials like wood or bronze, which can even have an increased resale value on the secondary market after humans and the environment have worn them down. At the same time, the wear and tear that is inevitably inflicted on less scarce and desirable materials is typically viewed as beyond repair, something to remove and toss into the bin before installing a new product.

With an understanding of the large carbon footprint that materials fabricated for the built environment contain, we must develop a new sensitivity to the materials that already exist in our built projects, whether they have the visual characteristics historically associated with well-worn beauty. In working to keep a more substantial percentage of our built environment away from the junkyard, cooperatives like these help to maintain a circular material economy that benefits the entire construction industry and society at large.

Architizer's 13th A+Awards features a suite of sustainability-focused categories recognizing designers that are building a greener industry — and a better future. Start your entry to receive global recognition for your work!