Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

We are quickly approaching 2030 and, with that date, the ambitious carbon-neutral targets to help avoid the worst of climate catastrophes. As the AEC industry is one of the worst sectors for carbon emission, we desperately need to take immediate action. Although green architecture has gained popularity in the past decade, it is most often associated with growing trees and plants — perhaps because of the term ‘green’ stands in for ‘environmentally-minded’ or ‘sustainable.’

While green roofs and walls have advantages —including keeping spaces cool in summer and warm in winter, harvesting rainwater, absorbing carbon dioxide and restoring urban ecology — we should bear in mind that growing plants requires careful maintenance and time, commonly years for the designed vegetation to grow until it can function with full carbon-absorbing capacity. In addition to waiting for the plants to mature, there are other changes that we, as architects, can make that will contribute to reducing carbon emissions in our industry.

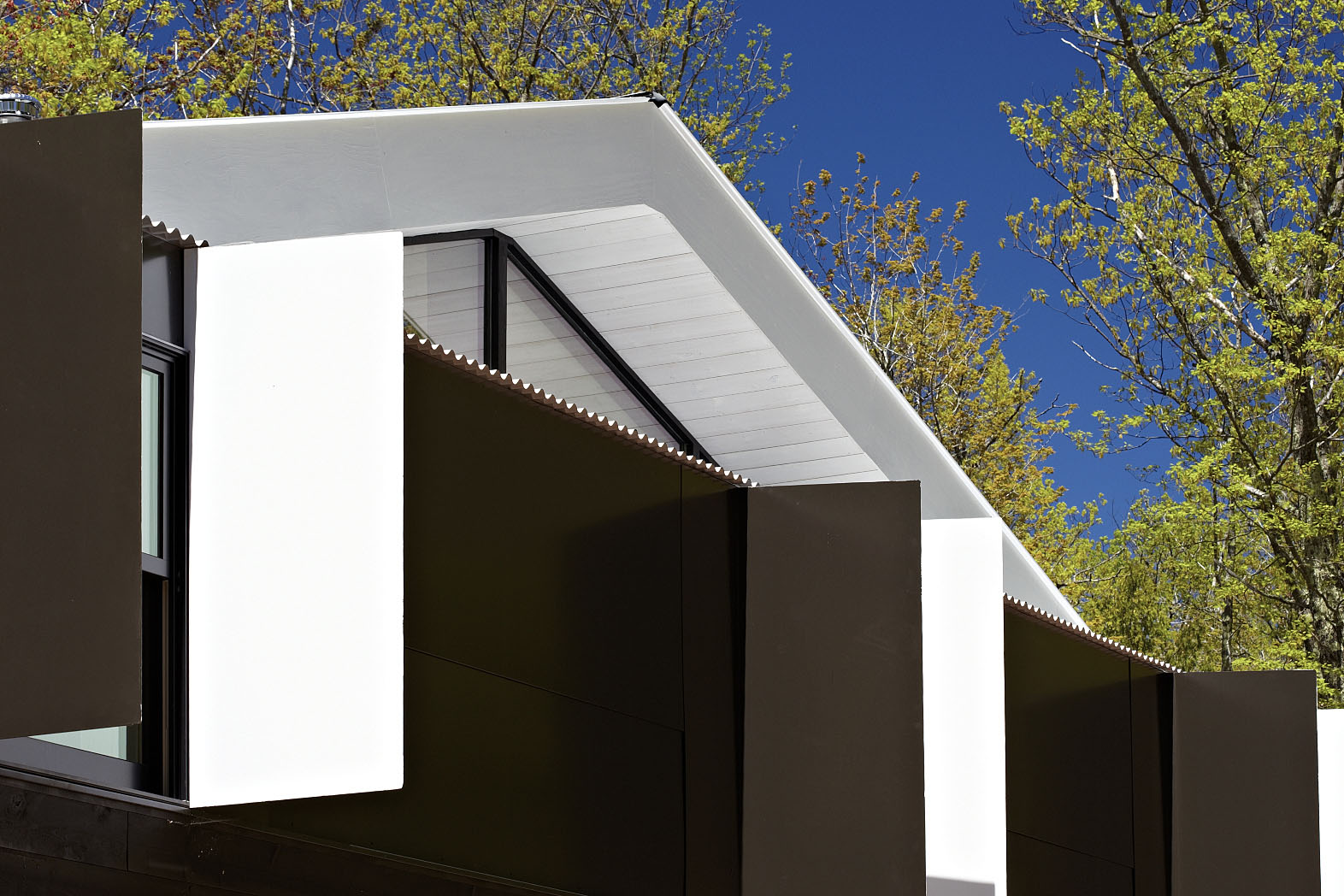

A private residential passive house by passivhaus-eco ® ARCHITEKTURBÜRO, Bamberg, Germany.

Passivhaus

Passivhaus standard means a building is designed in such a way that it hardly requires energy for heating and cooling, thus largely reducing the operational carbon emission. Passive houses usually have good insulation and strategic shading that avoid overheating in summer and thermal loss in winter. Within the building, airtightness and heat recovery ventilation system make sure the indoor temperature is always under control with sufficient fresh air. Coupled with solar harvesting and water recycling, the environmental impact of the building during its operational stage can be minimized.

Although Passivhaus is a standard that originated in Germany and is currently put into practice mostly in regions with similarly mild climates, with adaptations it has the potential to be applied to other climate zones such as tropical areas.

Adaptive Reuse near Brooklyn Navy Yard by Worrell Yeung, New York, NY, United States. The old timber floor joists are turned into tables and benches.

Adaptive Reuse

When there are existing structures on the site, the strategic reuse of the original buildings not only saves the energy of mass demolition, but also honors the energy that was already put into the production of those original structures, while also reducing the embodied energy and carbon required for the new structures. Salvaged materials might be degraded and become less structural; however, with structural innovations, in many cases it is still possible to use them for main structures.

Otherwise, it is also possible to craft salvaged materials into decorative pieces that add another layer of meaning to the project. The adaptive reuse of existing structures is a sustainable approach — not only from an environmental perspective but also from a socio-historic angle. Rather than “scrap and build,” new structures negotiate with historic buildings to meet contemporary sustainable and economical standards while allowing our cultures to develop sustainably as well.

New River Train Observation Tower by Virginia Tech Center for Low-Carbon Structures and Systems, Blacksburg, VA, United States | Jury Winner, 2020 A+Awards, Architecture +New Materials. | The project sourced timber from the site and turned low-grade hardwood into structural components.

Source Material Locally

Material and texture are important parts of a building’s aesthetics. Pretty projects that are shared across the internet now fuel our minds with inspiration. While many materials are now globally accessible, allowing us to pursue a variety of architectural styles, one should consider that any type of transportation induces energy consumption and carbon emission.

Therefore, it is crucial to know the materials that are most immediately accessible from the site, and to make use of this accessibility for cutting carbon emissions embodied in material transportation. Importing materials from another end of the world could make the building expensive, giving it status as luxurious and rare, but we should instead consider the value of good designs itself, which in turn makes our work as architects even more valuable in the long term.

House LO by Atelier Lina Bellovicova, Czechia | Jury Winner, 2021 A+Awards, Architecture +New Materials | The main structure is made of hempcrete.

Carbon-Storing Materials

Among the materials available around the site, our choices of material can be even refined to reduce its environmental impact by selecting carbon-storing materials and reducing uses of carbon-emitting materials. Concrete is notorious for its significant contribution to global carbon emission. The reason for this is (1) burning fossil fuels for cement production, and (2) the entire industry consumes so much concrete.

Apart from concrete, steel is a common structural material that also involves heavy fossil fuel consumption during its production (although metals are largely recyclable after a building’s demolition). The manufacture of natural materials such as timber and bamboo give out much less carbon dioxide, while growing them help store carbon dioxide in the air through photosynthesis. New bio-composite materials like hempcrete also have a similar carbon-storing effect during their production. Still, the carbon emission by material manufacture should be considered in conjunction with the accessibility of the material.

Week’nder by Lazor Office, Ashland County, WI, United States | Jury Winner, 2020 A+Awards, Architecture +Prefabrication

Prefabrication

Incorporating prefabrication also helps to reduce carbon emission and energy consumption in the construction process. As they gradually digitalize, design and manufacturing have become more and more accurate with the aid of software and components that precisely match and can be easily produced. Under such circumstances, prefabricating building components in factories can largely improve the efficiency of on-site construction, reducing the impact of construction on the site and neighborhoods. Pollution and waste are also more controlled.

Whether if buildings and building components can be prefabricated depends on the chosen material and structure. For example, freeform concrete structures are better to be cast on-site rather than prefabricated in parts for both structural performance and transportation ease, compared to lighter timber structures. Therefore, rather than a way of manufacture and construction, prefabrication should be considered at the early stage of design to maximize its efficiency.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

New River Train Observation Tower

New River Train Observation Tower  Week'nder

Week'nder