Architizer's new image-heavy daily newsletter, The Plug, is easy on the eyes, giving readers a quick jolt of inspiration to supercharge their days. Plug in to the latest design discussions by subscribing.

Virtual reality is the sort of much-hyped technology that is easy to roll your eyes at. Tech evangelists preach that it will change the world and that in a generation’s time we will all be living in Matrix-like bubbles entertained only by a stream of sensory input while our bodies laze in a vat of goo. While that may be true in the long term, right now the technology is already being adopted by gamers and technologists, and even architecture offices have started to cautiously embrace it. It’s not unheard of to use virtual reality to explain a project to a particularly plan-illiterate client, and the time may be approaching when a VR headset becomes a standard piece of office equipment.

But how is an architect to know where to begin? Virtual reality is a rapidly changing landscape, and it requires a careful coordination of software and hardware that has a steep learning curve. Digital models need to be converted into a format where they can be used by a virtual reality engine, then that engine needs to be run on a computer powerful enough to process the enormous memory and graphics requirements of VR and, finally, the user needs the right headset to experience the simulation.

There are several different Head-Mounted Displays (HMDs) on the market right now with prices ranging from $15 to $800 and qualities spanning a similar gulch. The first thing to determine is whether or not you are actually looking for a VR headset, as opposed to those offering other kinds of altered realities. Augmented and Mixed Reality headsets are similar to Google Glass, and rather than taking the wearer into a different synthetic universe, these sets will overlay the physical world with digital information. There are a variety of headsets offering this experience, but there are the most options and potential uses available for full Virtual Reality HMDs. Take a look:

The Oculus Rift, image via Ars Technica

Oculus Rift

The most well-known VR headset, Oculus Rift is something of a gold standard. Used mainly by the gaming industry, it’s now making its way to the design world. Coming in at $500, it’s not the cheapest bit of circuitry, but it is much more affordable than the clunky headsets of yore and is much more powerful than anything that came before it. One downside of it is that the environment seen through the headset needs to be powered by a powerful PC, so the Oculus is generally tethered to a computer by USB and HDMi cords. The headsets are comfy and padded but still relatively heavy, weighing in at a little over a pound, or about three times as heavy as the heaviest iPhone.

The screen for each eye has a resolution of about 1,080 x 1,200 pixels, which is great, but because the screens are so close to your face, even the smoothest visualizations will appear slightly grainy. Considering that the best HMDs still have only 1/60th the resolution capacity of the human eye, VR headsets have a long way to go to completely dupe the brain. Something else to note is that while you can use the Oculus to physically walk around a virtual room, it is generally best used for a seated experience. A simple Xbox One controller can be used to navigate, but there is also a dedicated controller now available, the Oculus Touch. Being a commonly supported piece of hardware and relatively easy to set up, the Oculus Rift is a good choice for novices who want to jump to the latest and greatest piece of tech.

The HTC Vive, image via Digital Trends

HTC Vive

The Vive is a competitor to the Oculus Rift with comparable quality. The major difference between the two is that while the Oculus Rift is best used while seated in a chair with a handheld controller, the Vive is primarily used for a walking experience, meaning that the user can explore a digital space by physically walking around a room.

The Vive also ships with two wands that the user can use to select and manipulate objects in the digital environment, making for the most immersive experience possible with today’s tech. On the downside, the Vive generally requires a room dedicated to its use, and its wall-mounted movement trackers can be tricky to set up and calibrate. It’s also the most expensive equipment available, coming in at $799.

Google Cardboard, via SUNY Stonybrook

Google Cardboard

While not nearly as sophisticated as the Rift or Vive, the Cardboard is extremely affordable (only $15!) and easy to use. Of course, that price doesn’t include the cost of the smartphone that is used as the screen to provide the visuals. Assuming you have that, all you have to do is download the proper files and app to your phone, slide the phone into frame, and you’re good to go.

While running the simulation off of a phone means there are no cables to trip over and you can take your experience with you wherever you go, it also means that you are using a much weaker computer than a powerful video-specific desktop. With that simplicity comes a loss of functionality. Some would even argue that the Cardboard experience is so simplified that it isn’t VR anymore, but merely a 360-degreevideo experience. That is because, unlike with the Rift or Vive, you can’t move through virtual space with Carboard; you are stuck in one location. You can move your head around and look around a virtual room with Cardboard, but that is as far as you can go.

Google Daydream, image via Google

Google Daydream

Daydream is Cardboard’s grown-up cousin. It has an elegant monotone covering and a simple head strap so you can actually wear it and not have to hold it up to your face while using it. Coming in at $79, it is significantly more expensive than Cardboard, but still much cheaper than other options. It comes with a handy remote for navigation and gameplay and works with Android and, of course, Google phones.

Samsung Gear VR, image via Amazon

Samsung Gear VR

The Gear is a collaboration between Samsung and Oculus that will use a Samsung smartphone for the screen, and it is basically Samsung’s version of the Google Daydream. At $129.99, it is more expensive than the Google option, but Samsung has more experience working in hardware, and the Gear works more smoothly with Samsung phones, which are much more common than Google phones. There’s a flat touchpad to control, and it’s a good reliable option for those looking to run VR off of their phones.

Zeiss VR One, image via Amazon

Zeiss VR One

The Zeiss is another option for a headset that works with a smartphone, but it’s set up to work with iPhones in addition to Android phones. If you are an Apple loyalist, then the Zeiss makes for a good choice, and its price comes just in between the Google and Samsung options at $99.99.

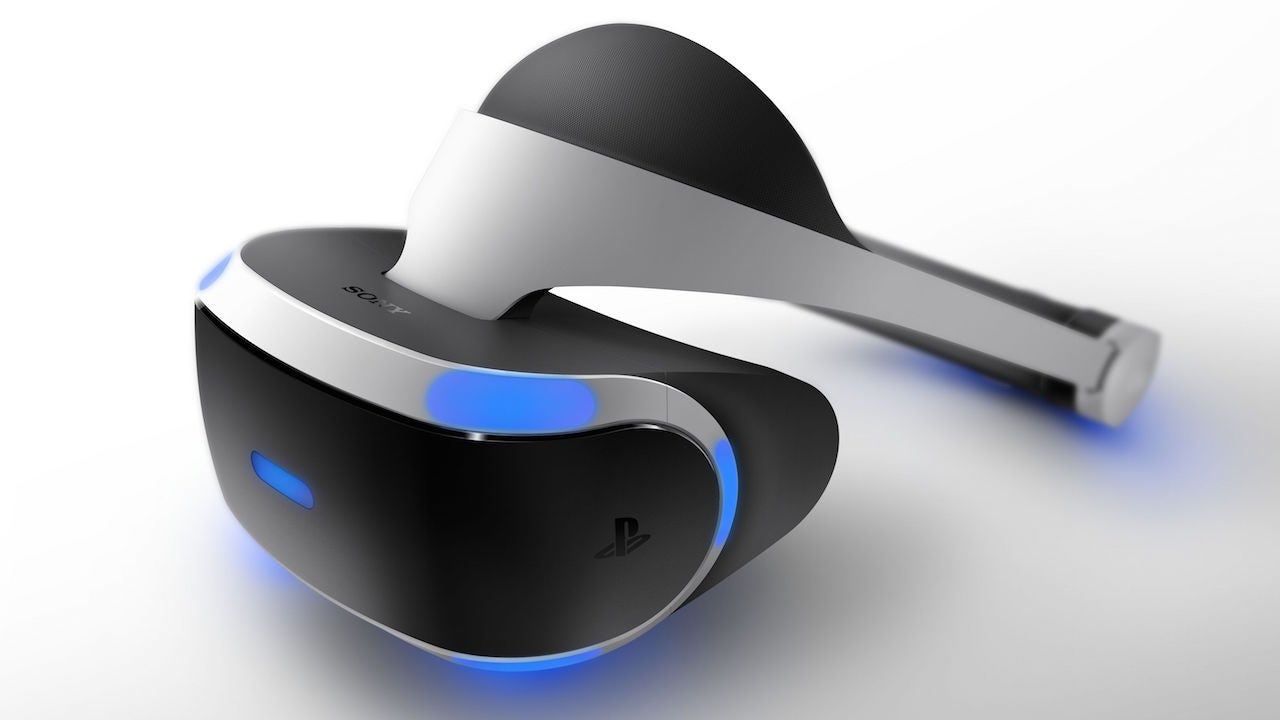

Playstation VR, image via GameSpot

Playstation VR

The Playstation headset obviously comes from the gaming world, and it’s a great piece of technology from a highly respected brand. It doesn’t work off of a smartphone, making it more like the Oculus Rift or HTC Vive, but unlike those, you can run the Playstation headset off of a Playstation console. If you’re already a big gamer, then that makes the Playstation VR a good choice, but if you are not, then the Rift or Vive are probably better choices. They both tend to perform slightly better, and at $399.99 for the headset alone, the Playstation option will set you back just about as much as the better options.

Avegant Glyph, image via YouTube

Avegant Glyph

The Glyph is similar to the Rift and Vive, but it has some quirks. Most significantly, the eye coverings don’t entirely block out the rest of your field of view. Instead, the virtual experience comes from a sort of bar that runs in front of your face and lets light in above and below. That could be distracting, but it also means that you can stay part of the physical world around you while wandering through dreamland. It also has a very different visualization mechanism from the other tech, one that looks pretty sci-fi.

Rather than using small screens to create the visual illusion, the Glyph uses “two million mirrors to project images directly to your eyes to recreate natural light.” Supposedly this offers a more fluid experience than other systems, but it also requires extremely careful calibration. Right now, the Glyph does not have a lot of compatible VR tools and is mainly used as a way to watch immersive movies, but Avegant promises that more is on the way. At $399.99, it falls in the same ballpark as its competitors.

Prices and specs correct at time of writing.Enjoy this article? Check out more of our Young Architect Guides:

8 Top Laptops for Architecture Students

The Top 3 Tablets for Architects and Engineers

Building Great Architecture Models

How to Convince Your Audience With a Powerful Project Narrative

How to Write About Architecture

Architizer's new image-heavy daily newsletter, The Plug, is easy on the eyes, giving readers a quick jolt of inspiration to supercharge their days. Plug in to the latest design discussions by subscribing.