This article is the first in a new series, Reinterpretations, that will identify a single construction component and trace it across the body of work from an architecture practice. For an in-depth explanation on the series and its aims, click here.

The American architecture practice DILLER SCOFIDO + RENFRO (DS+R) defines itself as ‘an interdisciplinary design studio that integrates architecture, the visual arts and the performing arts.’ A practice that began life through explorations of art installation and theater has developed into a force in architecture. It is argued DS+R has consistently worked off its origins to create built forms that conceptually explore the human condition. This article outlines that DS+R uses a particular construction component to facilitate conceptual investigations as architecture: the stair. Where the stair began as experimentations in the individual activating and engaging with space, it has resulted in the stair as the main protagonist in the configuration of the individuals-as-collective on display.

Section through the Eyebeam Museum of Art and Technology, 2001; courtesy of DS+R

“They contort the basic essence of a stair’s movement into a multi-directional component.”

This does not suggest DS+R intentionally or consciously use the stair, rather that we project analysis on to their work, suggesting a concurrent deployment of the stair to enact the essence of theatricality in the built environment. The trajectory of this idea is mapped out across the earliest of projects up until their most recent, advocating that DS+R use the stair as theatrical stage and social incubator for public use. To borrow a term from theater, DS+R create a ‘suspension of disbelief’ through their use of staircases not merely as circulatory aspect — taking building-users from one level to another — but as a form of communication — enabling and activating space either as an attractor or as a visual platform.

They contort the basic essence of a stair’s upward/downward movement into a multidirectional, multifunctional component. The idea of theatricality holds true in the stair; it provides aesthetic distancing where the viewer is seeing the banal street-view (High Line, New York) or block color (ICA, Boston) for the very first time. This is, however, not a discussion on framing; instead it is an understanding that the stair is the activator, creating a self-referential effect on the viewer through moments that distort perception and accepted norm.

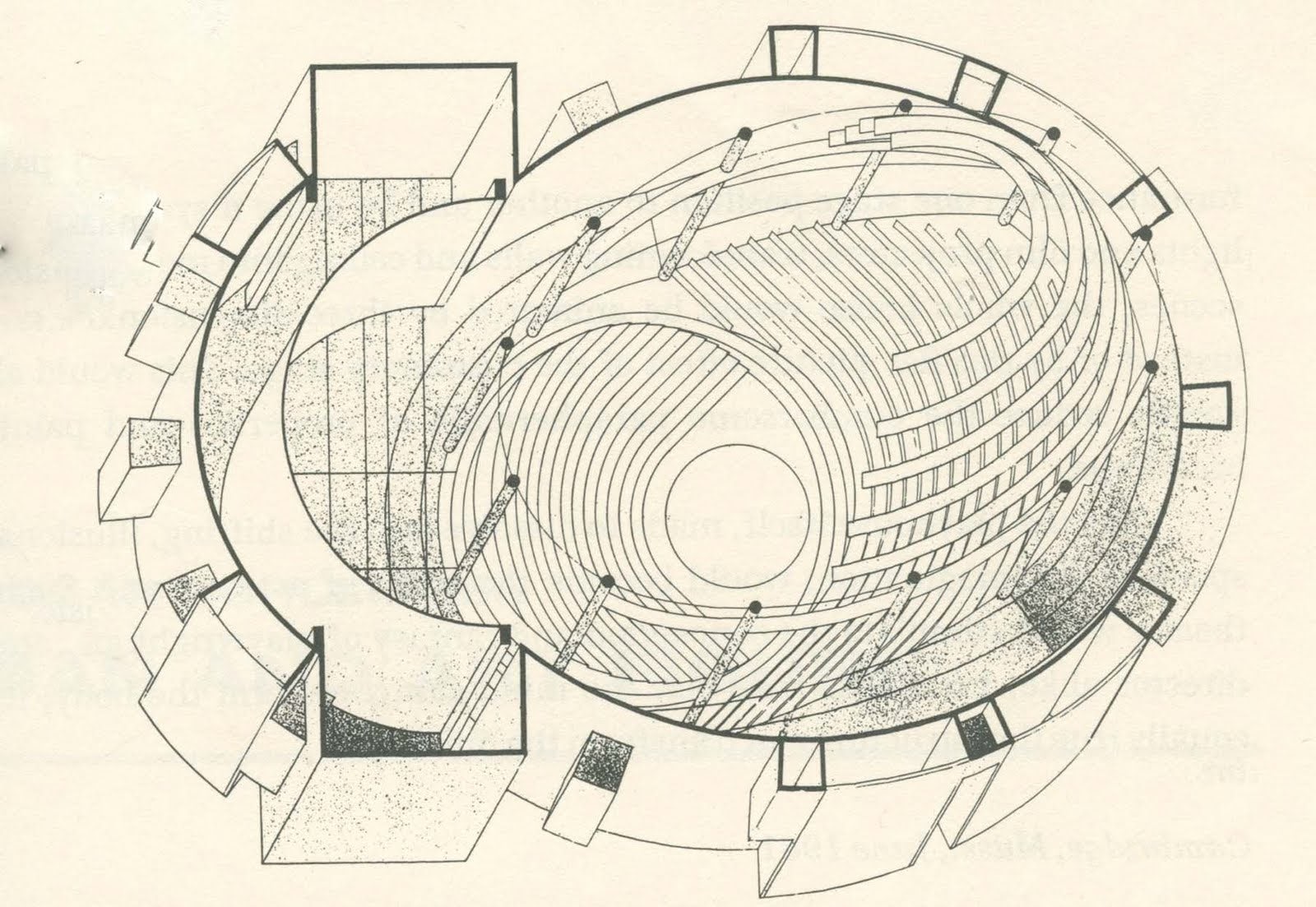

Walter Gropius’ Total Theater, 1927; via Sham’s Design Space

The Preexisting as Backdrop

In Diller Plus Scofidio: Blurred Theater (2011) by Antonello Marotta, connections are made explicit between the early works of founding partners Liz Diller and Ricardo Scofidio, noting Walter Gropius’ circular proscenium, or Total Theater (1927), and also Frederick Kiesler’s Endless Theater (1923), in which the Austrian-American architect ‘introduced the concept of dynamism into the theater scenography, with the aim of mixing actors and public in a new concept that abandoned the central, one-way public-show model.’

While it is unequivocal that DS+R was founded on the works of theater, exhibit and installation, the article presents a transition moment when the theatrical experimentations become spatial, architectural investigations in the stair. The stair is the device to incubate ideas borne in theater that produces a tectonic resolution to conceptual moments that sought to expose and question everyday life.

French philosopher Henri Lefebvre, in The Critique of Everyday Life (1947), believed the trivial should not be exempt from philosophical investigation. To Lefebvre ‘critique was not simply knowledge of everyday life, but knowledge of the means to transform it.’ Everyday life, as defined by Lefebvre, is everything that remains since everyday activities have ceased. Lefebvre suggests ordinary ‘moments’ in everyday life could extrapolate as moments of the extraordinary, which could lead to new modes of being.

Diller + Scofidio, Loophole, installation at Second Artillery Armory, Chicago, 1993; photography by Diller + Scofidio, reproduced by permission of DS+R

Many of DS+R’s early theater works or installations depend on a preexisting context or building as the backdrop to enable the questions each project raises. In Loophole (1992), for instance, the twin staircase in the Armory of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, acts as an ascending/descending narrative device.

“Movement is chronicled or archived and subsequently distorted.”

A video camera records footage of the stairway, window wall and views beyond, and as the video installation plays live — with views distorted — it actively disorients the viewer through the use of the stair and video sequencing. As the viewer ascends or descends, their movement is chronicled or archived and subsequently distorted. The viewer moves through the preexisting space, recorded in action and viewed elsewhere. There is a nod toward notions of surveillance in the work, but more significantly, the viewer-turned-voyeur is found looking at oneself in a staircase only to then become the object to be viewed.

Diller Scofidio, Facsimile, 2002; courtesy of DS+R

Such a conflation of recorded imagery and live streaming occurs some years later in Facsimile (2004), where a video monitor is suspended on the façade of the Moscone Convention Center, San Francisco. The monitor moves slowly across the elevation, transmitting either live or fictionalized footage from the interior of the building for the voyeurism of the street passersby. Actual building occupants and actual interior spaces are confused with prerecorded impostors. It is ‘a scanning device, a magnifying lens, a periscope and an instrument of deception.’

The deception of live footage and, in this instance, fictional prerecorded video toys again with the idea of surveillance — somewhat similar to Overexposed (1995), in which a 24-minute continuous video recording pans across the preexisting curtain wall of Gordon Bunshaft’s Pepsi-Cola building. These projects question the Modernist glass curtain wall by suggesting its ‘overexposure’ leaves, according to DS+R, ‘few shadow zones of privacy [ … ] glass has assumed the role of a representational surface, a performance screen.’

Diller + Scofidio, Overexposed, Getty Center, 1994; composite photograph by Ricardo Scofidio, courtesy of DS+R

Predating each of these examples is Withdrawing Room (San Francisco, 1986) — a project that centers on the domesticated language of the home (drawing room) to align it with the anxiety of social orders of privacy in the aforementioned.

As a series of ‘spatial meditations,’ DS+R exposed a conflict in the way we live through a focus on four aspects: the property line, intensifying ‘codes of privacy and publicness with regard to the building’s envelope’; etiquette, where the resident is offset against culturally determined rituals; intimacy; and an internal order. Withdrawing Room identified constructs so to break them down. The key component is what represents the property line/building envelope. To correspond the example projects, the envelope — just as the stair — is the preexisting component that succeeds in all it can expose or transmit.

Diller + Scofidio, the withDrawing Room, installation at Capp Street Projects, San Francisco, 1989; photography by Diller Scofidio, reproduced by permission of DS+R

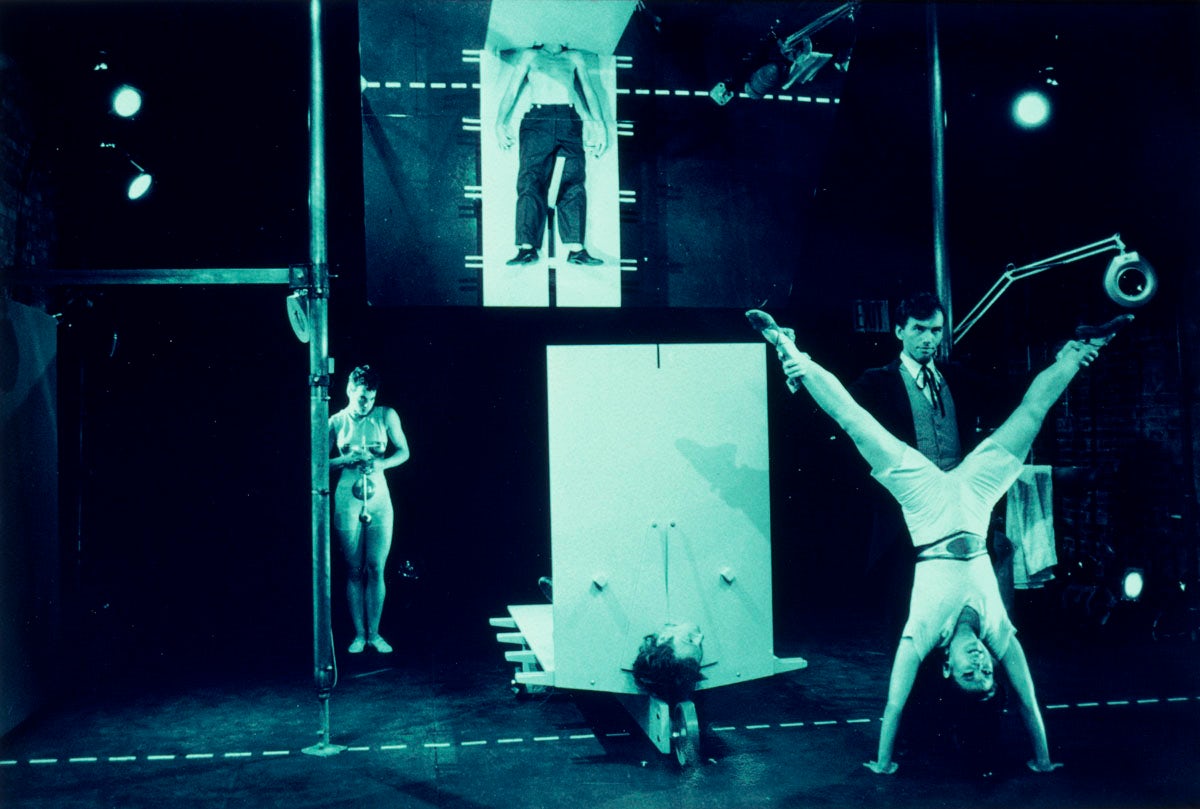

In a final but most prescient theater example, The Rotary Notary and His Hot Plate (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1987), DS+R split a stage in two with an opaque pivoting panel where the front is revealed and the back is ignored. Samuel Beckett, the Irish avant-garde playwright and a key figure of the ‘Theatre of the Absurd,’ conceived his first play (Eleutheria, 1947) as concerned with a man’s efforts to cut himself loose from his family and social obligations where the stage is divided in the middle.

On the right the hero lies passively in his bed; on the left, his family and friends discuss him without ever directly addressing him. Gradually, the action shifts from left to right, and eventually the hero summons up the courage to rid himself of his shackles. DS+R’s Rotary Notary … is akin as it ‘subverted the space of the stage.’ They offer a concurrent view of the actual (authentic), while the ‘mediated’ characters are viewed in space. All the while, the focus is on the individual-in-space and the audience’s perceived understanding of the locations, states and identities.

Diller + Scofidio, set design for “A Delay in Glass, or The Rotary Notary and his Hot Plate” by Susan Mosakowski; photography by Diller + Scofidio, reproduced by permission of DS+R

The individual is physically located in space in Loophole, Facsimile and Overexposed, as the stair or envelope is the ‘thing’ that permits a surveillance and is subsequently transmitted as the individual is watched. The act of transmission is dependent on the existing building playing its part as the backdrop for a viewer to be observed seemingly without their knowledge. In Withdrawing Room, the viewer is complicit in the spatial deception and is acutely aware of their role.

The Suspension of Disbelief

The ‘Theatre of the Absurd’ portrayed the world as an incomprehensible place, where spectators see the happenings on the stage entirely from the outside, without ever understanding the full meaning of the strange patterns of events. Theater critic Martin Esslin described the term ‘as a kind of intellectual shorthand for a complex pattern of similarities in approach, method and convention, of shared philosophical and artistic premises, whether conscious or subconscious, and of influences from a common store of tradition.’

“A building has conventions that depend on preconceived notions: You know that a stair means to ascend or descend.”

Theater is dependent on its audience accepting a scenario whereby they know what they will view is not a real event but a fictionalized account — a transgression from written word to performed sequence. This does, of course, require a ‘willing suspension of disbelief’ – a phrase formed by the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge and most notably used in the plays of William Shakespeare or, more recently, Tom Stoppard — so that the audience accepts the play on its own terms, temporarily giving over to the playwright’s vision of the world and the actor’s portrayal of it.

In Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead, the actors know they are in a play and realize they have to act out the play as part of their performance, meanwhile their performance is dependent on the audience accepting their pretense as characters in a play. The actors implore the audience to momentarily suspend their disbelief. Both are dependent on each other. Dramatic conventions are reliant on particular rules being as they are so to emphasize a deviation from the norm, and, in architectural terms, a building has conventions that depend on preconceived notions: You know that a stair means to ascend or descend, that a door denotes a threshold for which you open or close, that a wall demarcates programmatic space and so on.

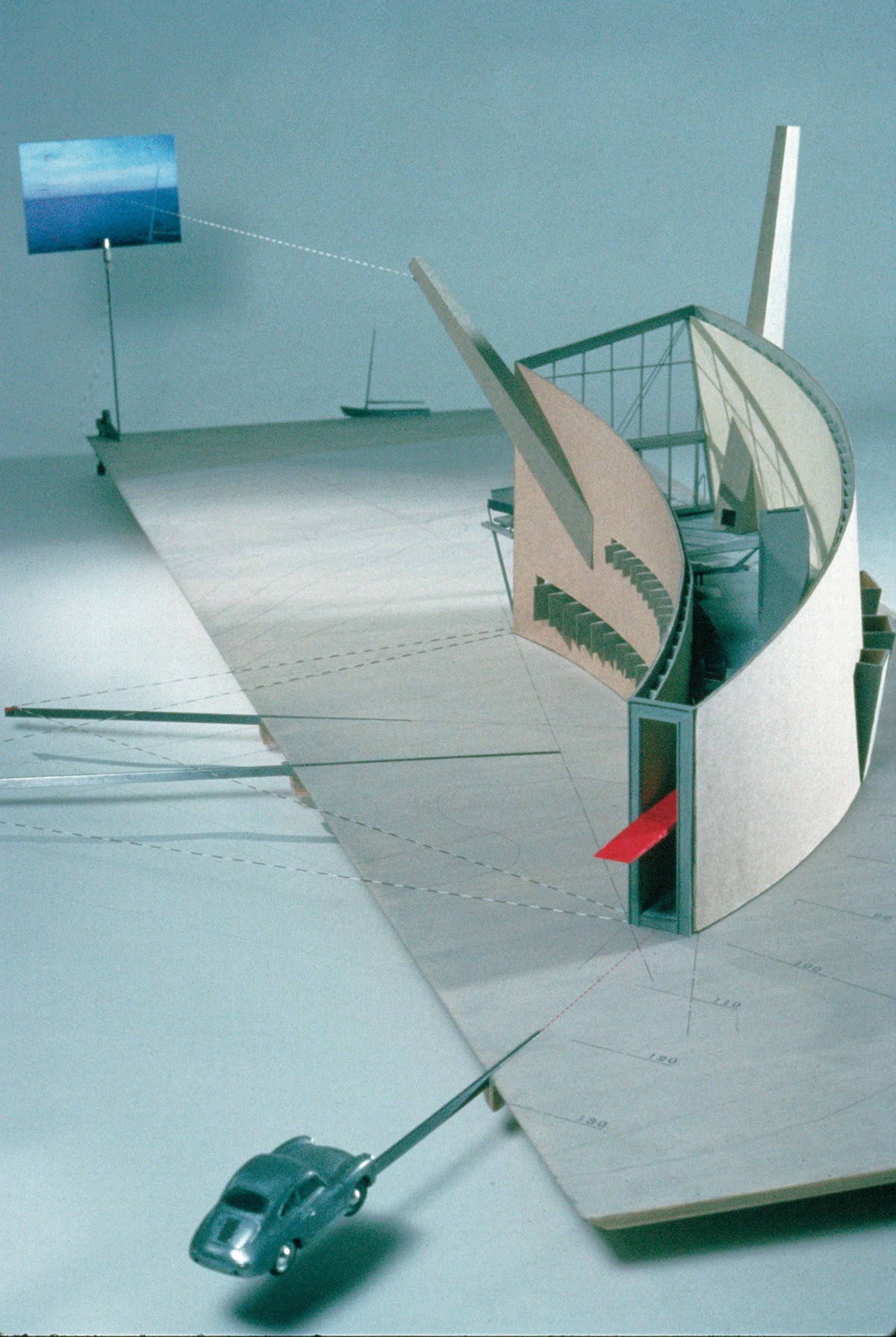

Diller + Scofidio, model of The Slow House, 1989; courtesy of DS+R

In a similar vein, DS+R highlight that a public conditioned to accepted conventions receives experiences through ‘a filter of critical standards, of predetermined expectations and in terms of reference, which is the natural result of the schooling of its taste and faculty of perception’ — as Esslin noted in reference to theater. DS+R ask for a self-critical act from the viewer. They may not discuss the ‘absurdity’ of the human condition, they merely present it in being. DS+R express ‘a sense of senselessness in the human condition and the inadequacy of the irrational approach by the open abandonment of rational devices and discursive thought.’ The crossover between the Theatre of the Absurd and DS+R lies in how the spectator receives the work. Each spectator should find their own meaning and perpetually suspend disbelief.

Supplementary to the argument posited is one of DS+R’s earliest architecture projects (unrealized), Slow House (1991), a private residence that, according to the architects, is a ‘physical entry to an optical departure, or simply a door to a window.’ The project is dependent on the idea of control both in the mediation of the view and also the control in movement or direction of the user through space. The transition from door to window provides a sequencing from the authentic to the mediated.

Diller + Scofidio, view of visitor on ramp, The Blur Building, Swiss Expo, Yverdon-les-Bains, 2002; courtesy of DS+R

While SlowHouse is a controlled spatial design with a focus on the resulting view, the BlurBuilding (Swiss Expo, 2002) prevents the viewer from understanding the extents of the building on display. SlowHouse dictates the view and Blur dismantles the view. The stair, in DS+R, is an amalgamation of these devices. On the one hand, it offers controlled, level-to-level circulation, and on the other, it thrusts the individual to the foreground of the envelope, continuously activating its elevation thus preventing the passerby from recognizing a static façade.

The Theatrical Stair

As a circulatory device, the stair is a purely functional piece of architecture and enables a user to move up/down between levels. Constrained by regulation, the stair is a difficult building component to innovate. Its rise and run are predetermined as is the number of steps before a landing, handrail and balustrade requirements are set and the use of tactile indicators and other safety measures are established. Even the location of the stair in the layout of the building is generally mapped by circulation distances and exit widths. To begin to alter the stair — to add meaning or communicate through the stair — is no ordinary feat.

“To begin to alter the stair is no ordinary feat.”

DS+R achieves this in a multitude of ways — both physically and experientially. Take, for example, the HighLine Part I (2009–2011) where there is an amphitheater-like space that uses stair and landing that angles the view downward to the street below. Not only is it a mathematical feat (incorporating rise and run and an accessible ramp down to the base of the window to the street), but it also creates a moment of reflection and refuge from the High Line and the busy city street below. An in-between space for the everyday citizen to contemplate the ordinary in a new dimension.

© Iwan Baan

The Sunken Overlook at 10th Avenue, The High Line; New York, N.Y.; photo by Iwan Baan

Incidentally, this moment may have its origins in the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), Boston (2006), where DS+R located a multimedia room cantilevered from the building to create a room that looks down into the harbor. Somewhat similar to Slow House, in both of these projects, the viewer is directed to the view. By default of their location (either above the street or the harbor-side), they inadvertently become an activated and ever-changing façade on display.

Similarly the entry into Alice Tully Hall (2009), itself a theater in New York, has an inverted stair on the street where the public can sit and look into the lobby — creating an amphitheater surrounding the building for general public use. Unifying across all of these projects is that the viewer begins at the top of the landing and descends into a prescribed view of everyday life below — playing with a sense of vertigo, instability and vulnerability through the suspension of the stair positioned downwards.

© Diller Scofidio + Renfro

Practice Rooms, School of American Ballet, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York, N.Y.; photo by Iwan Baan

Around the corner from Alice Tully Hall is the entry to the Juilliard School (2009), a project that includes a staircase wrapped into seating at its lobby. This, in turn, creates a place for informal gathering, meeting and for viewing the street. The School of American Ballet (2007) allows borrowed views from intersecting studio spaces that also permit views in/out through the liquid crystal glazing at the dance instructor’s discretion.

Such physical studies of the stair all turn what would be a functional element (a stair to take a user from point A to B) into a place for social incubation: a multifaceted condition where one can meet, watch and survey. Comparatively, the Creative Arts Center at Brown University (2010) programs six intersecting half-levels with its circulation core that permits prescribed and limited views. Interestingly, in its conventional use (point A to B) DS+R produce a disjunction between levels with the stair operating always as continual.

Section Viewing North, School of American Ballet, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York, N.Y.; courtesy of DS+R

© Iwan Baan

Practice Rooms, School of American Ballet, Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts, New York, N.Y.; photo by Iwan Baan

Its very conventionality allows for the fluctuation in program and the resultant prescribed view. It is a significant conceptual twist on the stair as activator. In bisecting programs, the stair, in these instances, calibrates views by rejecting a view in totality.

“ … the stair scythes between … for purely voyeuristic purposes.”

Again in a continuation of domesticated language, similar to withDrawing Room, DS+R state ‘the landings [at Creative Arts Center] of the main circulation stair are expanded and conceived as vertically stacked living rooms for serendipitous and planned encounters.’ Fascinatingly, DS+R implement the use of a glass wall to expose the sectional splits in floor plates as the stair scythes between, reminiscent of dividing the stage or exposing the transmission of the activity beyond for purely voyeuristic purposes.

In Flesh: Architectural Probes (2011) DS+R produced a book that ‘maps out strategies for “contractual space” in which architecture can perform critically within encoded spaces of privacy and publicity.’ The human body is an ever-presence in their work in relation or opposition to the built environment.

© Iwan Baan

Lobby with view of stairs and escalator, The Broad Museum, Los Angeles, Calif.; photo by Iwan Baan

“A darkened, shadowy crevice awaits.”

At the Broad Museum (Los Angeles, 2013), DS+R produced the ‘veil and the vault’ in reference to the envelope and the building’s entry point. With this intriguing double play on the word ‘vault’ — otherwise known as a groin vault — DS+R induce a humanistic quality through this body-part reference. It is unsurprising then to find the access to the main gallery spaces are via a stair and an escalator through this vault. The user is unaware of the space they are to enter, and instead a darkened, shadowy crevice awaits.

Program and circulation are explicitly separated at the Culture Shed (due for completion, 2019). It is the most overt distinction between each in the oeuvre of DS+R. The shrouded exhibition space is ‘mediated,’ concealed from immediate view; while along the property line, the street passerby is able to view all of the users on ‘authentic’ display in its staircase along the elevation.

Diller + Scofidio, Eyebeam Museum of Art and Technology rendering, 2001; courtesy of DS+R

In the aforementioned stair examples, the importance of the landing should not be understated. They create the stage for the everyday viewer. Projects such as the unrealized Eyebeam Institute (2004), Museum of Image and Sound (Rio de Janeiro, 2016) and Columbia University Medical & Graduate Education Building (2016) share a similarity in form.

The main elevation in each is visually stimulated by a ramp ‘ribbon’ folding through the floor levels. A ramp may not fully adhere to the principles of a stair, but it remains dependent on regulations of height and landing and so maintains a stair-like quality.

Exterior View, Medical and Graduate Education Building at Columbia University; courtesy of DS+R in collaboration with Gensler

In each of the ‘ribbon’ projects, the individual is on full display, they are the live video stream and the curtain wall is the monitor. Individuals are no longer aware of the surveillance camera because the camera is no longer there. They are in fact the performance screen itself. The connection is, in each instance, oversized landings enable gathering spaces, theatrical stages for the viewing pleasure of the voyeur.

In Eyebeam, visitors and residents are combined; Museum of Image and Sound offers a promenade as ‘vertical boulevard’; and Columbia provides ‘the study cascade’ where the snaking form of the circulation engages the facade.

“Vertical Boulevard,” extension of beach promenade along façade, The Museum of Image and Sound; courtesy of DS+R

The Extraordinary Everyday

Just as Henri Lefevbre suggested transformation of everyday life could be found in the very processes of everyday life, it is suggested DS+R use the stair to critique the everyday condition of an individual-in-space at a point in time. The stair is used beyond mere ordinary function to be made absurd or extraordinary; it is projected forward for the viewer to take as it is or take something from.

The stair, when thrust to the elevation as social activator, becomes the performance screen or backdrop with the focus on the individual and their movement, the façade exposes and/or transmits. People are free to roam but are complicit in their own surveillance. The viewer-turned-voyeur once experienced vertigo and is now exposed as the object to be viewed.

“The stair is essentially a two-way street of acceptance.”

In the DS+R oeuvre, they first develop theatrical installations as body-in-space, to stairs bisecting program and disassociating views, to the stair as truly theatrical architecture. DS+R are imploring the viewer to suspend disbelief, to look beyond the stair as a conventional stair, and instead to see a collection of individuals as an animated façade as a picture of everyday life.

And for the individuals to use the stair not as a typical stair, but — as Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead demands the actors accept they are in a play for their audience to accept the suspension of disbelief — to improvise its use. The stair is essentially a two-way street of acceptance.