Architects: Showcase your projects and find the perfect materials for your next project through Architizer. Manufacturers: To connect with the world’s largest architecture firms, sign up now.

In 1986, Mexican architect Enrique Norten founded his firm TEN Arquitectos (Taller de Enrique Norten) in Mexico City. Fifteen years later, in 2001, the firm gained international prominence when it opened an office in New York City. Focused on creating efficient forms of public space, Enrique Norten met with Architizer to discuss his vision and the projects he is working on.

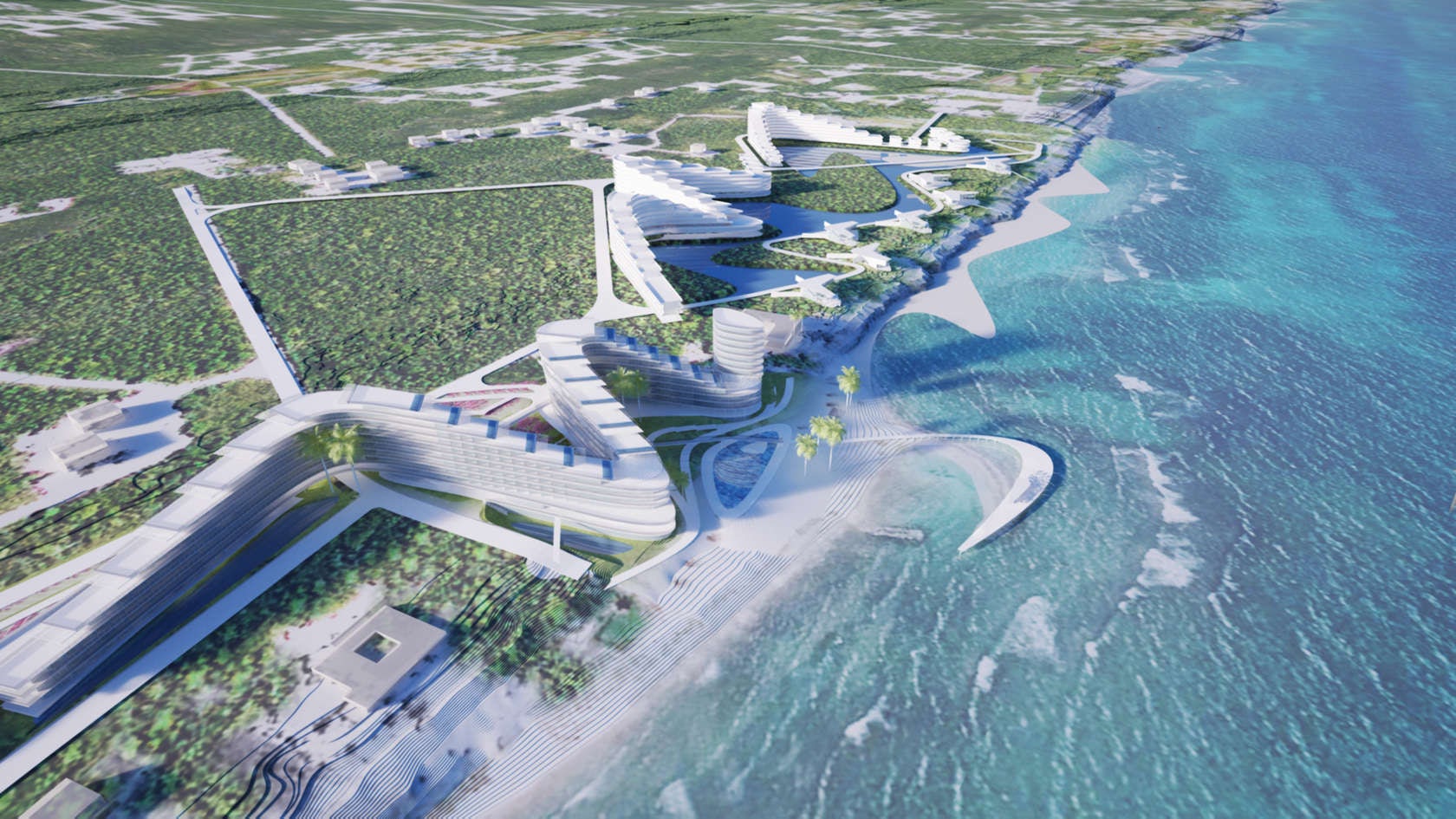

While TEN Arquitectos is currently occupied with several private projects — the Cayman Island Resort in the Caribbean, a residential project in Miami and a facility for NASA in Cleveland, Ohio — the firm is also working on many public institutions throughout the United States, including the Mexican Museum in San Francisco, a mixed-use tower and public plaza for Two Trees Development in the Downtown Brooklyn Cultural District and the newly opened 53rd Street branch of the New York Public Library in Manhattan.

Rendering for the Mexican Museum, San Francisco, Calif.

Rendering for the NASA Campus, Cleveland, Ohio

Rendering for the Cayman Islands Resort, the Caribbean

Enrique Norten is optimistic that working with different organizations and levels of the government will allow his firm to experiment with new forms of public space. Through his work, Norten is striving to explore how architecture can completely blur the boundaries between the public and the private realms. The architect believes his buildings should deliver architecture as an additional public service that responds to the functional necessities of an existing landscape and culture.

In 2016, TEN Arquitectos hosted an architecture workshop at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, posing the question “What Is the Future of Public Space?” Many students, planners and architects were present to explore the concept of public space at various scales, all the way from metropolitan regions and cities to individual buildings. A workshop like this one is a unique way for architecture firms to interact with the public, demonstrating TEN Arquitectos’ interest in learning from the users of everyday architecture and public space by breaking the barriers of communication between the design firm and the ultimate inhabitants of their buildings.

Enrique Norten speaking at the Museo del Barrio, for the Diseño series presented by the Cooper Hewitt

Workshop at the Cooper Hewitt; photos: Susannah Brown, courtesy of Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum

The question of public space is central to Norten’s practice, as it represents the largest good that an architectural project can deliver to its environment. “I don’t believe that the whole modern idea of architecture as an object … really sustains itself anymore,” he explains. “I only see architecture as part of a texture … and it’s a texture where everybody is contributing to the creation of what we call public space.”

TEN Arquitectos believes that rather than seeing public space as a void that is left over from a project, it should be considered an intentional part of a design that benefits from the future activity of users. “In these sorts of very capitalistic countries … people understand public space as anything that is not mine or anything that I don’t need to maintain, any leftover from my property is public space,” says Norten. “That may be public — owned by public entities — but it doesn’t mean that it is [truly] public space or, at least, [it is] never good public space.”

© Stefen Turner | aerial photographer

Renderings of DBCD South, Brooklyn, N.Y.

When working hand in hand with private developers — whose aim is naturally to promote and make profit from a project — TEN Arquitectos’ role is to propose solutions to maximize efficient public space without compromising the rentability of the project. “Institutions understand the difference,” says Norten, particularly cultural and nongovernmental associations. The team at TEN Arquitectos is currently building a residential tower, flanked by a public plaza, for the Downtown Brooklyn Cultural District at the intersection of three major Brooklyn arteries: the Flatbush, Ashland and Lafayette Avenues.

For this project, developed by Two Trees, the architects successfully negotiated the creation of a new level of public space. If the client did not initially hold this vision for the project, TEN Arquitectos was able to present the opportunities that this public space could bring for the neighborhood and community. The resulting design is particularly beneficial to the tenants of the first few floors — dedicated to cultural institutions like the BAM, MoCADA, 651 Arts and the Brooklyn Public Library — who therefore have the possibility to extend their programs to the public spaces at street level.

Without taking away from much of the footprint, the project places retail space at street level to respond to profit-generating needs for the site while creating new, elevated areas for the public to sit, congregate and activate the space with entertainment and more.

Casita, New York, N.Y.

TEN Arquitectos has also experimented with urban interventions like Casita, a “kit of parts” installation in a park in the South Bronx borough of New York City. “It was almost an industrial design project,” explains Norten of the project, a pro bono popup for a nonprofit organization. “It was a lot of fun and it shows how, with very little intervention, architecture [can] really transform the opportunities of certain public spaces, which in this case are semi-abandoned or semi-utilized parks in the city.”

In his architecture, Enrique Norten blurs the boundaries between the building and the city: “There are projects … where we try to extend the city. We try to let the city flow into the building or the other way around, extend the architecture into the city.” His ideas are inspired in part by historic concepts of public space: Norten makes reference to Nolli’s 18th-century plans of cities where public spaces, whether open or covered, were drawn the same way, creating a uniform language to identify the nature of those places.

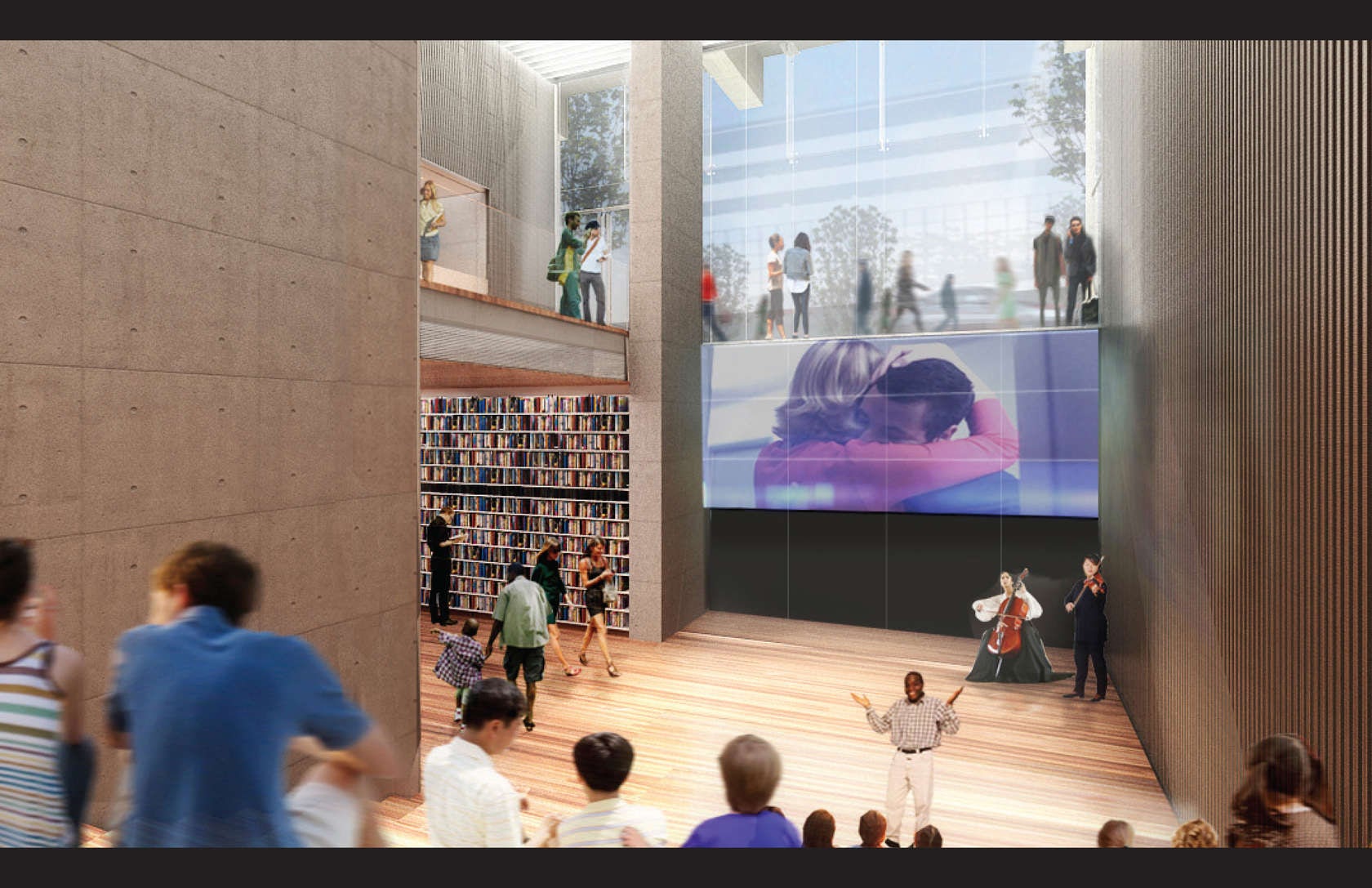

Renderings of the 53rd Street NYPL branch, New York, N.Y.

The challenge, he explains, comes in making a façade that is both inviting and transparent. Norten’s most recently completed project — a new branch for the New York Public Library, that opened on June 20 on 53rd Street in Manhattan — is exemplary of the efforts to create an interior public space that connects with the public at street level and citywide activity.

The multimedia library features a very open space completely visible from the outside through a full-height glass façade. The interior makes reference to the organization of plazas or amphitheaters, and visitors can sit on stairs to enjoy the cultural program — film screenings, theater, readings and more — taking place on stage-like spaces in the library. Norten compares this organization to a form of manmade topography, energized by design elements like the glass façade.

© Evan Joseph Images

Photos of Mercedes House, New York, N.Y.; photo credits: (top) Evan Joseph, (bottom) Alexander Severin

To Enrique Norten, most of the projects that are both funded and promoted by civic or cultural institutions allow for greater experimentation and flexibility around the assets that the building can give back to the city. “It doesn’t matter if it’s New York or Mexico City, in the end … it’s the idea of the city,” he explains. “Obviously there are some cultural tonalities in the way the spaces are energized or activated, but in the end it’s the same thing: On one side how to really define what public space is and then define the hierarchies of that space or the processions within those spaces.”

Enrique Norten is one of many architects who travel between two offices. Some architects have offices in different cities of the United States and often on different continents, taking advantage of the cultural influences one can encounter by working with teams from all over Europe, Asia or Latin America. Like New York, Mexico City is highly cosmopolitan and dynamic, and Norten speaks enthusiastically of the energy that exists in both offices.

Hotel Americano, New York, N.Y.

For 28 people in his New York office, Norten counts more than 12 different nationalities. His Mexico office is composed of a majority of Mexicans from all regions, architects from other Latin American countries and Spain as well as Poland and Romania. Though different, those energies fuel each project that the firm works on, combining the architects’ diverse backgrounds with Enrique Norten’s ultimate vision — the common denominator — to produce the best spaces for the public.

To explore more projects by TEN Arquitectos, make sure to visit its complete Architizer profile here.

Find all your architectural inspiration through Architizer: Click here to sign up now. Are you a manufacturer looking to connect with architects? Click here.