As New York City planners and developers continue to develop the long-neglected waterfronts along the East River, a new proposal begins to take shape. In North Brooklyn, the former industrial site that was home to the Astral Oil Works refinery has finally been secured by the city after a contested battle to purchase the last piece of land from a private owner.

The Bushwick Inlet Park is a 28-acre site that straddles a small river inlet and sits directly adjacent to Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighborhood. The City of New York has promised to convert the former refinery, which contains 10 oil tanks and a concrete structure, into a park for local Greenpoint and Williamsburg residents to have a greatly anticipated expanse of green space. A neighborhood organization Friends of Bushwick Inlet Park has formed since the city acquired the first parcel of land to make sure the wishes and needs of the city are heard throughout its development process.

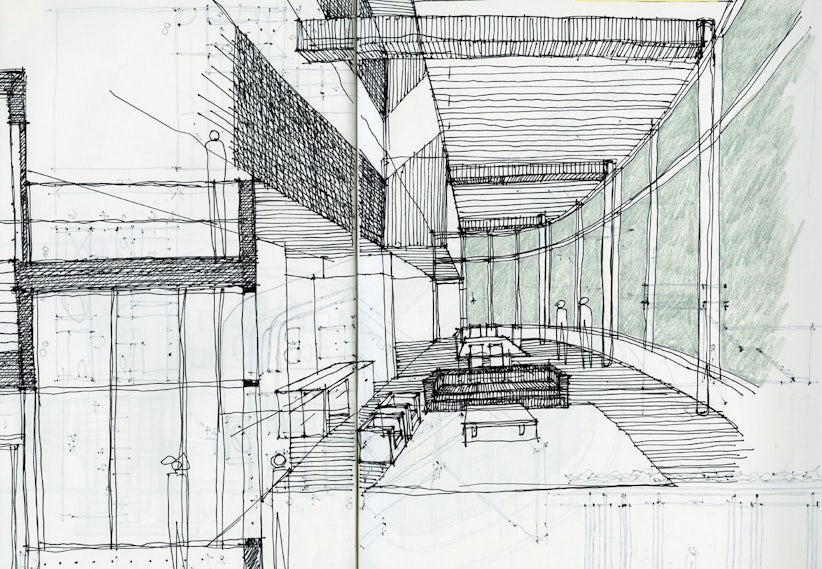

Aerial rendering of Maker Park

Just as the full plot of land has been acquired, a new proposal, Maker Park, emerges from a team assembled by a group of advocates, designers and planners, including The Municipal Arts Society, architecture firm Studio V and landscape firm Ken Smith Workshop, among others. The team envisions an alternative proposal to the projected plans first released by the city in 2007, which has promised to demolish the existing oil tanks and structure to create as much green space as possible on the site. Alternatively, the Maker Park team is advocating for the repurposing of these structures to create a dedicated community maker center and a series of play and installation spaces.

“The current plan is to demolish [the tanks], and what we would like to propose is to keep them and do something incredible with them, breathe new life into them and thereby preserve not only the history of the site, but also the amazing creative culture around the neighborhood,” says Karen Zabarsky in an interview with Architizer. Zabarsky is one of three founding members of the Maker Park project and a creative director at Kushner Companies.

© Brett Beyer

The current site contains 10 existing oil tanks from the former refinery.

Zabarsky helped to form the Maker Park proposal after she had been put in touch with Zach Waldman, a digital strategist who had been living and working in the building on the Astral Oil Site until he was evicted in 2015. “For about 10 years prior to 2015, there had been a pretty impressive community of artists and makers and entrepreneurs that had kind of made this building one of the centers of Williamsburg creativity,” says Waldman about the site’s creative history. “Wu-Tang Clan recorded there, the Jewish Tinder, called JSwipe, was started there … This was a kind of a last of its kind community, and it would be a shame to not recognize that in any future plans for the neighborhood.”

Motivated to sustain the creative legacy of the former site and its contributions to the Williamsburg community, Waldman worked with Stacy Anderson of the Municipal Arts Society, who eventually brought Zabarsky into the fold. “The three of us solidified this idea and vision, and the final step was really taking it from just the three of us with our vision to making it into a real, solid team and a real vision that was backed up.”

Maker Park proposes an inlet boardwalk and boating program.

This vision to retain the industrial architecture of the existing site goes deeper than its most recent creative history. “When this project was conceived of, we didn’t really know a great deal about the history of the site,” says Anderson, “but it quickly revealed itself that the legacy of the planned site for Maker Park had a very direct link to our vision for this site.” The owner of Astral Oil Works was Charles Pratt, who used the money he made from selling his refinery to Standard Oil in 1874 to subsidize the founding of Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, “which can be regarded as the original maker space of Brooklyn in that it was founded with the intention of endowing the newfound industrial workforce with the skills and the tools that they needed to thrive in this new economy,” says Anderson.

“What was really unique about the space was that it was open to all people, irrespective of class and gender. It was a very kind of inclusive institution and very progressive for its time,” she continues. Inspired by the equalizing spirit of this institution, the trio saw potential to make Bushwick Inlet Park not just a green space, but a civic commons, and they felt retaining the historical architecture of the site was the best way to communicate Pratt’s legacy.

The project envisions transforming the oil tanks into a series of play spaces, gardens, installations and performance venues.

Eventually the team found a designer in Studio V, a New York–based architecture and design firm led by Jay Valgora that has extensive experience developing New York City’s waterfront as well as in areas such as adaptive reuse and sustainability. Responding to the raft of monumental residential developments that have been popping up on Brooklyn’s waterfront, Valgora saw the chance to do something more personal. “We see an opportunity at Bushwick Inlet Park to not just strip everything away … and create just generic solutions that could be anywhere, we want to preserve the unique characteristics of that site and create something that’s really special, that’s all about Greenpoint and that captures that unique character,” he says in our interview.

Studio V has subsequently on-boarded a range of practitioners including landscape architects Ken Smith Workshop, environmental attorney Michael Bogin, environmental engineer and remediation specialist Matthew Carroll and lighting designer Suzan Tillotson, who have all committed to develop this project pro bono. “We thought, in order to make this a real vision — not just a series of ideas, not just a bunch of pretty drawings — we would need to work with the kind of people that we work with all the time on waterfront projects,” says Valgora.

Besides assembling a professional team, the architects and founders of Maker Park are committed to integrating the community into the proposal’s planning process. “We want to create real solutions that take into account all the different conditions, maintain an open process where we’re engaging with all community groups and all city agencies,” says Valgora. Following up on two open design meetings this past spring and summer, the group is hosting a community meeting next Tuesday, December 6, to present its first round of renderings for community feedback. “Our biggest mission with this event that we have coming up is to bring as many members of the community as we can possibly attract, and we have all kinds of different outreach strategies for doing that so people can really see the vision, they can meet the team, they can ask us questions,” says Karen.

While the group’s proposals to keep the oil tanks on-site have been received with interest, they have also been met with concerns from members of the community who worry about the contamination from the tanks and who feel they will compromise the amount of green space made available. The Maker Park team is hoping the December 6 meeting will quell any fears inspired by the proposal, “We want to assuage concerns that the community [has] that we would look to preserve these tanks at the expense of public health,” says Anderson. “We want to also share our vision on a wider scale, show people we aren’t greatly diminishing the amount of green space by keeping these structures, and in fact we’re … approaching it in a new way.”

The team has a long way to go to secure their project, but they remain steadfast in the strength of its mission and committed to developing the project with the community. Stay tuned for more details on the project’s evolution.

Information on the Maker Park Community Meeting taking place on December 6 can be found here.