The jury is deliberating... stay tuned for the winners of Architizer's A+Product Awards! Register for the A+Product Awards Newsletter to receive future program updates.

In 1994, Stewart Brand published How Buildings Learn, a book that changed how architects think about time. His central insight was that buildings aren’t single objects but nested layers, each moving at different speeds. The site is eternal. Structure lasts centuries. Skin gets replaced every few decades. Services (wiring, plumbing, HVAC) cycle every fifteen years or so, and the space plan shifts with tenants and trends.

And then, at the very center, spinning fastest of all: Stuff. Furniture. The layer that changes “with the seasons and the current trends.” The ephemeral layer. The disposable layer.

Brand’s diagram became canonical. But by the time he published it, King Living had already been proving it wrong for seventeen years.

The Australian company started with a simpler question: why did sofas keep ending up on the curb? David King, founder and visionary, visited secondhand shops around Sydney, studying how things failed. What he discovered was timber frames that were cracked at the joints, arms that gave way under the lightest pressure and tired cushions that compressed never to come back. The failures, he found, weren’t random. They were clearly designed to behave like that. So King did what any good designer would do: he designed the flaws out. Creating steel frames influenced by automotive suspension, covers that came off and went back on easily. He created furniture that was built to be serviced, not replaced.

The rest of the industry? They kept spinning. Brand’s model described what most manufacturers were already doing, and thats what they kept doing. Shockingly, the average sofa still only lasts seven years and Americans throw away over twelve million tons of furniture annually. Eighty percent of that ends up in landfill.

Recent research suggests this way of thinking was a huge mistake. Firms like LMN Architects and MSR Design have begun quantifying the cumulative carbon impact of that innermost ring, and their findings are startling. Over a building’s sixty-year life, the embodied carbon of furniture, cycled every seven to fifteen years, can equal or exceed the carbon embedded in the structure itself. One MSR study found that furniture alone accounted for more than half of a commercial renovation’s total embodied carbon. What we’ve learned is that the fast layer is where the damage accumulates.

This fall, King Living opened a US showroom in Portland, its third in the United States, marking the beginning of a journey to reverse how a whole new subset of consumers thinks. Architizer spoke with CEO David Woollcott about building furniture for the long run.

You’ve described King Living as a “forever brand.” When you look at a space, what role do you think furniture plays in shaping the stories people tell about how they live there?

David Woollcott: Furniture is the framework of people’s lives. It’s where they gather, celebrate, and rest. A sofa becomes the setting for family moments, a dining table is the witness to milestones, and a bed supports our daily renewal. When furniture is made to endure, it becomes a backdrop to people’s stories for decades.

Spaces are defined as much by how they’re furnished as by how they’re built. How do you see King Living’s modular systems shaping the way people move through and inhabit space?

Traditional furniture locks you into one decision, one layout. The beauty of modularity is freedom. The customer shapes the furniture to suit their lives, not the other way around. As a business philosophy, it’s transformative because it creates longevity. People don’t have to purchase a new sofa when they move house or downsize. They can rearrange, expand, or simplify it. That ability to evolve is what allows our customers to truly inhabit a space on their terms.

In architecture, we talk about buildings that “age well.” What allows a piece of furniture to do the same?

Timeless design is built on discipline and the removal of unnecessary details. Clarity of form, enduring materials, and thoughtful engineering that anticipates change. Our best-selling designs have remained icons for over two decades because they embody those values. Their modular foundation, steel frame, and balanced proportions give them a timeless quality that evolves with their owner and space. King Living reinforces this longevity with a 25-year steel frame warranty, a commitment that ensures the design endures for a lifetime.

King Living has always designed for change, bringing pieces to market that can be reconfigured, refreshed, and repaired. How does that choice connect to current conversations about adaptable and resilient design?

Adaptability has been part of King Living since day one. We were designing modular, repairable, recoverable furniture before “resilience” and “circular design” became part of the global conversation. What’s different now is that society has caught up. Customers expect products to adapt to their ever-changing lifestyles and living spaces.

Australian design has a reputation for being relaxed yet rigorous, connected to light, landscape, and lifestyle. How do you see that spirit translating when you take the brand overseas?

The spirit of Australian design is more than the aesthetic. It’s an ethos. Australian design is shaped by our environment, our climate, and our relaxed way of life. When we enter markets like the U.S. or the U.K., customers sense that honesty. It’s rigor without pretension, comfort without compromise. That authenticity is what resonates globally.

You’ve worked in cars, appliances, and now furniture. Each of those touches daily life in a profound way. What have you learned about how people connect to the things that surround them?

In every category I’ve worked in, I’ve seen that people form emotional bonds with the products they use every day. At BMW, a car was pride and identity. With appliances, it was reliability and trust. With furniture, it’s comfort and connection. It’s truly part of your daily rhythm. What connects all three is the desire for products that respond to real human needs, not purely technical specifications. Connection happens when products evolve in step with people’s lives.

The Portland showroom brings King Living into a city with its own strong design culture. What kind of conversations do you hope will happen there between designers, architects, and the public?

Portland was a natural fit because it’s a city with a progressive design culture. I hope our showroom becomes a hub for dialogue and inspiration. Conversations about sustainable living, about the role of modularity in design, about how furniture can evolve with its inhabitants. We are at the forefront of furniture’s future.

Beyond comfort and durability, what role does experimentation play in the design process at King Living? Are there risks you encourage your team to take, even if they don’t all make it to market?

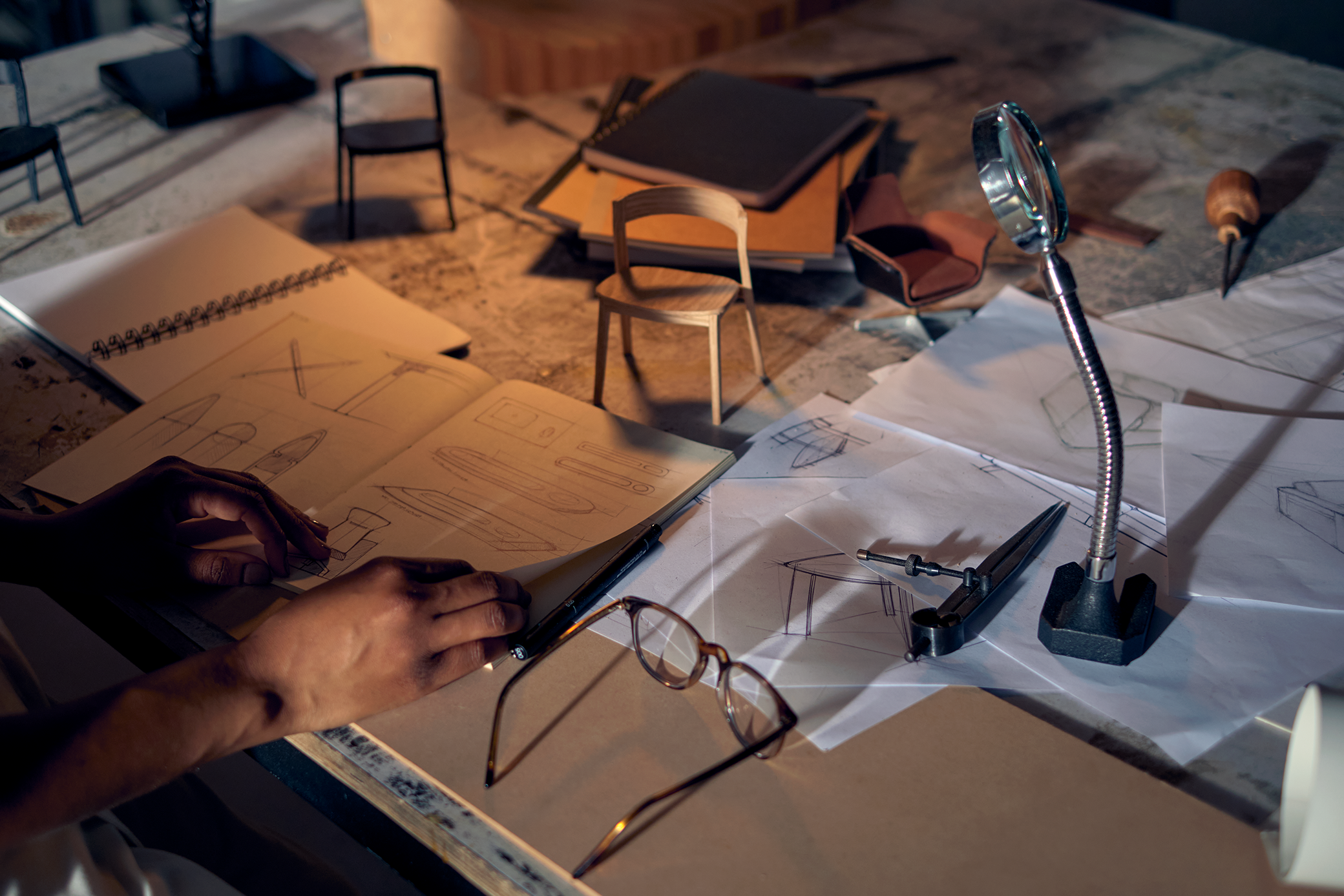

Experimentation is vital. If every prototype makes it to market, you’re not taking enough risks. Our founder, David King, encourages the in-house design team to test new materials, integrate emerging technologies, and continually innovate and refine. Being a vertically integrated company, we are in a unique position. We have fully owned and operated manufacturing facilities and teams with decades of experience that enable us to push the boundaries.

Repair, refurbishment, and reuse are part of King Living’s story. Do you think attitudes toward furniture, and perhaps architecture too, are shifting from ownership to stewardship?

Yes, and I think it’s one of the most important cultural shifts of our time. Ownership implies disposal at the end of the cycle. Stewardship implies care, maintenance, and responsibility. That’s how we’ve approached design from the very beginning: steel frames that can be recovered, covers that can be replaced, parts that can be repaired. It’s our role to make it easy and desirable for customers to choose stewardship over replacement. If we can be part of a movement that shifts the conversation from “What’s new?” to “How can I make this last?” then we will have lived up to our purpose.

Finally, if we spoke again in twenty years and looked back at this moment, what would you hope to say about King Living’s contribution to the way people live with design?

I’d hope to look back and say that King Living showed the world a different way to think about furniture. That we proved adaptability and sustainability could be the foundation of a global brand. That we influenced not only how people furnish their homes, but how they think about living in them. And above all, that we stayed true to our founding family values, built on a desire to do things better and differently.

Brand’s layers were meant to describe how buildings actually work. But descriptions have a way of becoming prescriptions. If furniture is classified as fast, it gets designed as fast, and the carbon costs compound with every cycle.

King Living’s bet is that the hierarchy isn’t fixed. That furniture can be slow if you build it that way. The warranty runs for twenty-five years. The frame is steel. And the company commits to continuing to service sofas from the 1980s.

The fastest layer, it turns out, really can slow down.

The jury is deliberating... stay tuned for the winners of Architizer's A+Product Awards! Register for the A+Product Awards Newsletter to receive future program updates.

Images courtesy of King Living.