Bob Borson is creator of the famous Life of an Architect blog, a Texas-based architect at Malone Maxwell Borson Architects and an indispensable guide to professional practice.

I get asked a lot (as in every single day) about architects and their abilities to sketch.

“Do you have to be good at drawing if you want to be an architect?”

or

“I want to be an architect, but I can’t draw. Doesn’t everybody just do 3D modeling these days?”

No, architects don’t just do 3D modeling these days. And, no, you don’t have to draw well to be an architect. I’m not an artist, but I can sketch well enough to communicate an idea, and that is what’s important to me.

Sketching is a skill — not a gift — and with time and practice, anyone can become proficient enough at sketching to effectively work through problems and communicate their intent. I wrote an article a few years ago titled “Your sketches speak for themselves,” and the basic premise of the article was that despite the fact that I’m not a very artistic sketcher, I do believe that I can sketch well enough to have the sketching process serve a role and allow me to work through problems graphically.

In that article, I scanned nine consecutive pages from a sketchbook of mine that was 15 years old and showed — in all its unedited glory — what my sketches looked like and how I used them to think through my design. Rereading that post, coupled with my job change, gave me the idea to reevaluate the premise of that article and see if I still believed how important sketching is to an architect.

In my current office, my partner Michael Malone sketches A LOT. He literally sketches All. The. Time.

Prior to me joining the firm, he was the be-all and end-all, go-to guy in the office for design, business development, office management, employee training and development. We have 11 employees and a lot of work, so let’s just say Michael has to work nonstop to wear all the hats for the responsibilities he is carrying. As a result, he tends to work when — and where — he can. Because he spends a lot of time out of the office, he tends to sketch in sketchbooks and not on trace paper, which allows him to not lose any of his work. All of the sketches in this post are his except for the last few. It will be obvious which ones are his and which ones are mine.

Also, all of the sketch images in this post can be clicked on, allowing them to open up full size.

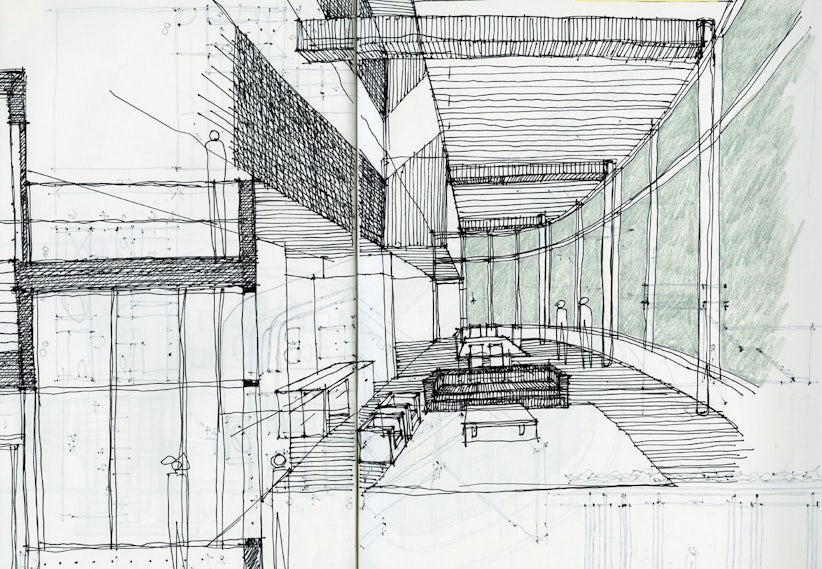

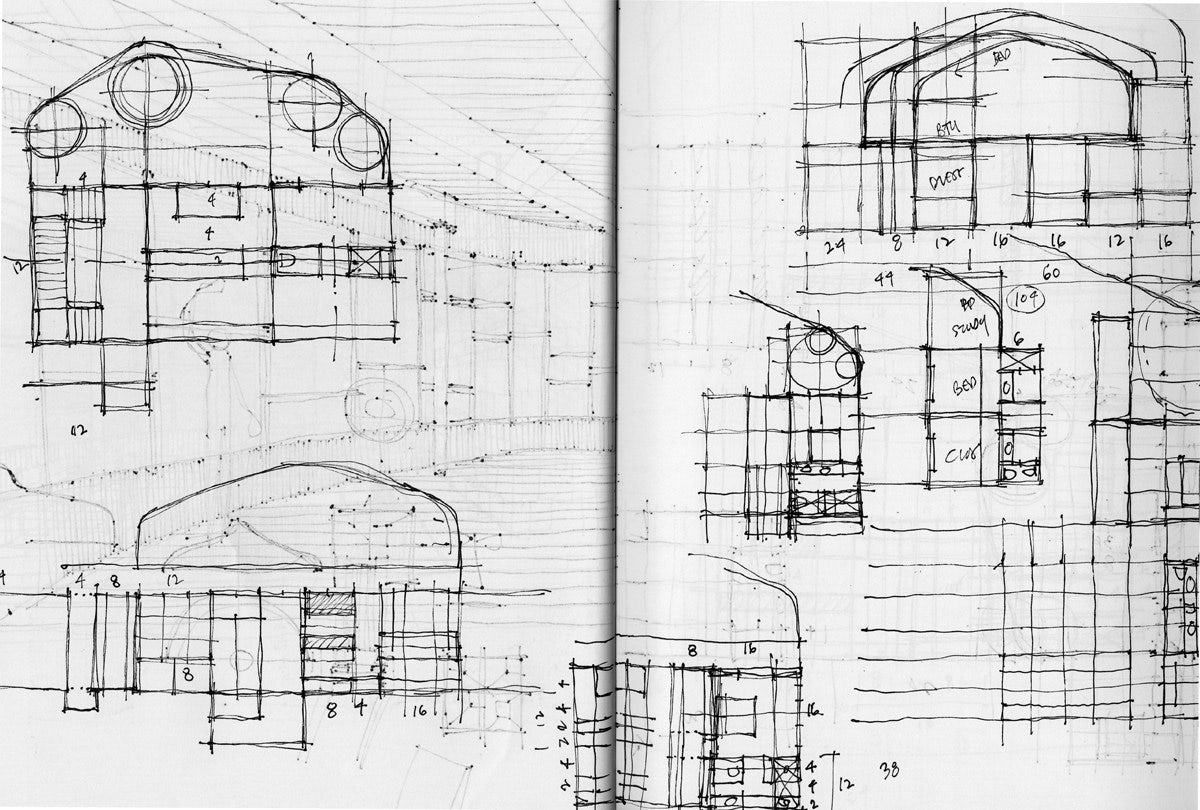

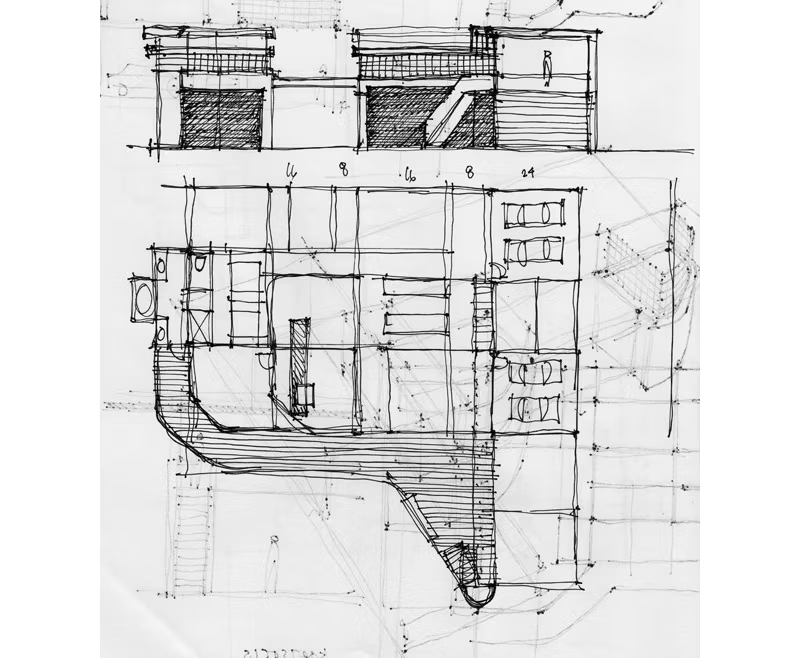

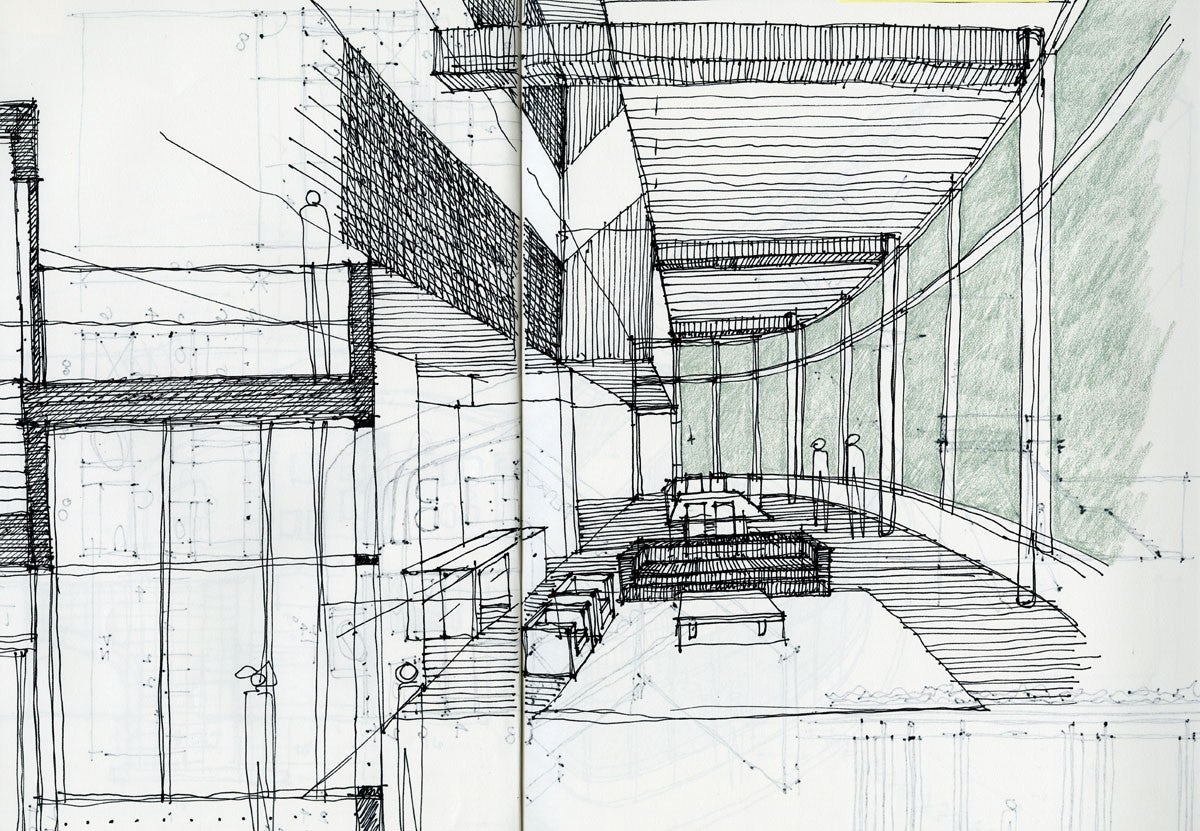

Michael designs his projects in his sketchbooks. Afterward, he has them scanned and distributed to the project architects in our office who will reference them to do their work. You can see from these sketches that the problems he is trying to think through are at a very high level. Massing, floor plans, elevation studies, interior spaces … most of it schematic design stuff. When I told Michael I was going to write this post, I asked if I could borrow his most recent sketchbook so I could scan a few pages. I briefly explained the point of the article, and, afterward, he summarized my explanation with the following comment:

“ … My sketches create problems, while your sketches solve them.”

He wasn’t wrong, but to hear it put that succinctly wasn’t entirely fair to him. The point I am trying to illustrate is how architects use sketches to work through different sorts of issues. You’ll see, as you scroll through these first several sketches, that Michael is pretty good at sketching, he definitely has a style. He doesn’t do these drawings for presentation purposes. They are simply how he works through and catalogs his ideas. I’m pretty sure he never thought that they would end up on the world’s third most amazing, yet highly irrelevant, architectural website — and now Architizer. While he and I both sketch daily as part of doing our jobs, our sketches are different — not just in their qualities and techniques, but in the goals we have when we set out with pen and paper.

All of Michael’s sketches here are from the same project. I choose them because they represented his schematic design studies and included plans, sections, elevations, interior perspectives … just about everything except process and construction drawings. That isn’t to say he doesn’t sketch those things, but he just doesn’t do it very often; it isn’t part of the problem he is exploring unless it’s expressed as part of the design.

The sketch above is the last one in this post from Michael — a quick section elevation to look at the relationship between a mosaic window wall, a light monitor, the roof deck above and its adjacency to a green roof. Most of his sketches are more about the “what” and not the “how.” The “how” is where I come in.

At the time of when I wrote this post, I had been in my new office for just two weeks, but I was involved with most of our active projects. Because part of my role here at the office is employee development, I spend a lot of my time sliding from workspace to workspace answering technical questions and discussing how we can document the construction of the project while maintaining the original design intent. It’s a role I am comfortable with because I think I’m pretty good at design, but I’m also interested in how buildings physically come together.

As much as I don’t want to say I’m that guy … You know, the one who sits down in a design meeting and asks “Where’s the mechanical closet?” or “You know, we are going to need a beam through here right?” But the truth is that I kinda am that guy (just way cooler).

Most of my sketches tend to be on trace paper or on plotted-out sheets. I have frequently described myself in the following way:

“Ask me what time it is, and I’ll tell you how to build a clock.”

I don’t mean to flatter myself when I use this phrase. I typically mean it in a disparaging way because I am overly verbal … I will literally talk your head off if we’re both not careful. As I have matured, this attribute has actually turned into an asset. I am good at shepherding people through a process with considerable patience. I really like to explain things. As a result, when the younger architects and interns have a question, I don’t just tell them the answer, I pull out my pen and paper and sketch it through with them; hence, ask me what time it is, and I’ll tell you how to build a clock.

My sketches are definitely not pretty like Michael’s, but they serve me extremely well. They help me work through problems.

These are my sketches. They are almost always snippets and small pieces of a larger part. I tend to sketch the assemblies and relationships between parts, try to answer the question How does something work?

These sketches were created as I sat with one of my new coworkers trying to work through a heavy-timber truss in one of our projects. These sketches frequently have text in them, questions that I ask myself, questions for other people to think about.

Architects should sketch. I am convinced of this.

I haven’t ever — I mean EVER — personally met an architect who I thought was a good designer who didn’t sketch. Maybe it’s because the process takes time, requires a person to slow down and think through what they are doing. These sketches don’t have to be beautiful drawings; they aren’t art. They are the result of a process, a creative process that is somewhat unique to the world of designers. You may not think you are very good at sketching, but if it helps you work through your thoughts, I would argue that you are, in fact, very good at sketching.

Cheers,

Bob

This post first appeared on Life of an Architect. All sketches courtesy of Life of an Architect and Michael Malone.