Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.

Designed by Beijing-based firm OPEN Architecture, the shocking 10,000-square-foot UCCA Dune Art Museum is a recently completed structure carved into a strip of sand in northern China. For many years prior, strong winds had been the sand pushing back from the shoreline, eventually forming one of the last remaining dunes of such a massive size in the region. The architects were inspired to use this natural formation as the foundation for the new museum, creating a design inspired by children’s tireless digging in the sand.

Image via Metalocus by Wu Qingshan

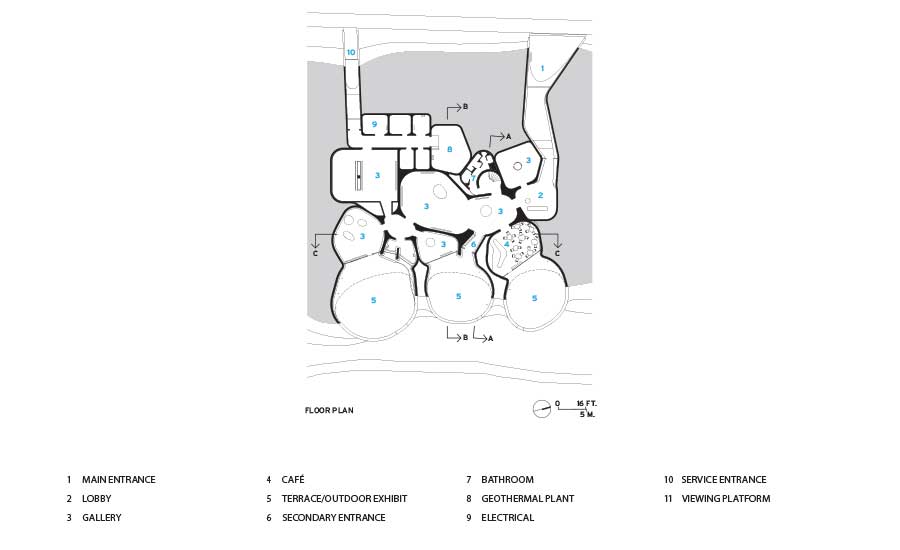

For the UCCA Dune Art Museum, the architects created a series of interconnected spaces. On the exterior, these spaces disappear neatly into the landscape, while on the interior, they resemble cavernous holes that draw visitors in like a cave — one of the first sites of both human habitation and artistic creation. Each cell is home to a different element of the museum’s rich and varied program, including galleries of different sizes, studios and a café.

Image via Architectural Record

Diagram by OPEN Architecture via Architectural Record

Upon entering the building, visitors first pass through a long, dark tunnel and small reception area, after which the space dramatically opens up into its largest multifunctional gallery. Within, a large skylight aperture allows a beam of light to enter and permeate the entire space, creating an apparent contrast between the vastness of the open sky and the enclosed nature of the building.

Image via Open Architecture

From early on, OPEN knew that they wanted the UCCA Dune Art Museum to be entirely cast in concrete. However, the architects were not as set on the precise techniques that they would harness to achieve this, considering a vast range of possibilities before settling on the final approach. For instance, they considered fabricating steel ribs and trusses capable of supporting concrete formwork; however, this approach proved to be both overly time-consuming and costly.

Next, they explored using CNC-milled foam, which proved far too fragile. Finally, and perhaps most experimentally, OPEN looked at erecting mounds of sand that could be sprayed with shotcrete, and hollowed out once the material was completely set.

Image via Architectural Record

Departing from each of these earlier explorations, the architects ultimately settled on a technique that had been floating in front of their eyes the entire time. Located along the coast of Bohai Bay, the beachfront region is well known for its locally constructed fishing boats. After all of the aforementioned fabrication techniques turned out to be unfeasible, the architects consulted local boat builders with longstanding expertise in creating complex, curved wood formwork.

Image via Architectural Record

The method of construction, which drew on the strength of this local knowledge, turned out to be both iterative and adaptive. OPEN kicked off the process by using rebar to create a lattice structure, which served as a critical guide throughout. The contractors then bent wood slats, planks, and boards into formwork, making on-the-fly adjustments along the way. Challengingly, different curves required different sizes and orientations of wood, and the concrete needed to be thicker at the base of the building. Meanwhile, the upper sections — where doorways and skylight apertures would eventually peak out — required extra rebar reinforcement.

Image via Metalocus by Ni Nan

Image via Metalocus

While the project inevitably involved complex digital modelling, it also involved a whole lot of “eyeballing”, impromptu creativity, and the redrawing of several details in response to the challenges that arose.

Image via Architectural Record

In the end, the architects were completely unembarrassed of any visual flaws that resulted from the unorthodox construction process. Acknowledging just how beautiful the imperfections of construction were, they decided to celebrate them as central aspects of the design. With its evident patterns, textures, and even visible staple marks, the concrete was left exposed, revealing its history and method to visitors for many years to come.

Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.