Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

This autumn will see the release of a new film by Wes Anderson. The French Dispatch has been described as “a love letter to journalists set at an outpost of an American newspaper in a fictional 20th-century French city.”

Fans of Anderson know what to expect: a cinematic world that feels much more put-together than the one we inhabit everyday. As a child, Anderson admired the “slightly heightened reality” of Roald Dahl’s children’s stories and has spent his career bringing a similar sensibility to the big screen.

Not everyone finds Anderson’s distinctive aesthetic delightful. New York Magazine critic David Amsden once complained the director had become “pickled in a world of his own creation.” Image: Tony Revolori and Saoirsie Ronan in ‘The Grand Budapest Hotel’ (2014)

With meticulously decorated sets, droll dialogue, and perfectly symmetrical shot composition, Anderson’s movies are catnip for perfectionists. One gets the sense that his greatest pleasure, as an artist, is making sure everything fits together just so.

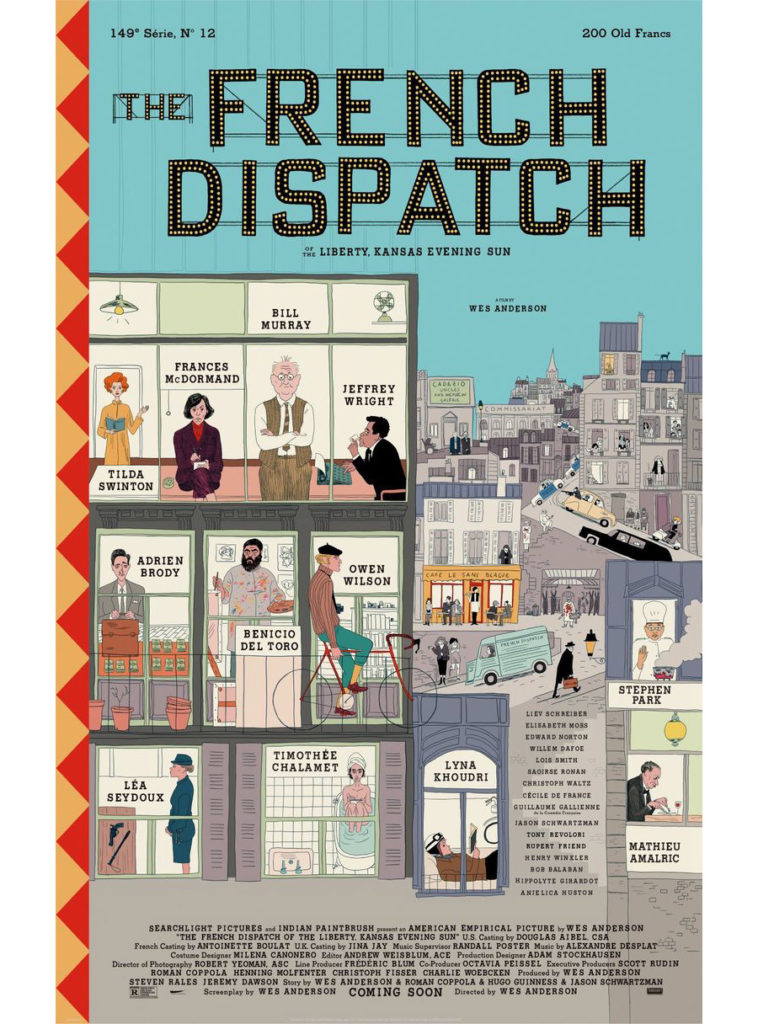

Architecture plays a central role in this decidedly un-naturalistic approach to cinema. Nearly all of Anderson’s films feature a central structure around which the action revolves. In The Royal Tenenbaums, it was a family home in Manhattan, while in The Darjeeling Limited it was a train that carried American tourists across India. In The French Dispatch, judging by the promotional poster, it will be the newspaper’s offices.

Promotional poster for ‘The French Dispatch’ (2020). The poster was designed by illustrator Javi Aznarez.

In each of these cases, Anderson uses various techniques to ensure that the viewer gets a complete picture of the structure. He doesn’t just provide an impressionistic sense of place, but actually lays out how the spaces fit together, sometimes using architectural models and cutaways.

This impulse toward diagramming and contextualization cuts strongly against the grain of most Hollywood directors, who like to throw viewers in the midst of the action to encourage direct absorption in the plot. In contrast, Anderson treats his viewers like an architect treats their clients, leading them step by step through the world he has lovingly created — whether they are interested or not.

The following structures have played starring roles in Anderson’s films.

The Harlem brownstone where The Royal Tenenbaums was filmed has become a popular photo op for cinephiles. Image via movie-locations.com

The Royal Tenenbaums (2001)

“Royal Tenenbaum purchased the house on Archer Avenue in the winter of his 35th year.” So begins one of the most iconic films of the aughts, a work that is as much about place as it is about character or plot.

The Royal Tenenbaums is set in a storybook version of New York that was inspired by how Anderson imagined the city while growing up in Texas as an avid reader of the New Yorker. The addresses and place names in the film are all invented, yet the shooting locations are all real and located either inside the city or in nearby New Jersey.

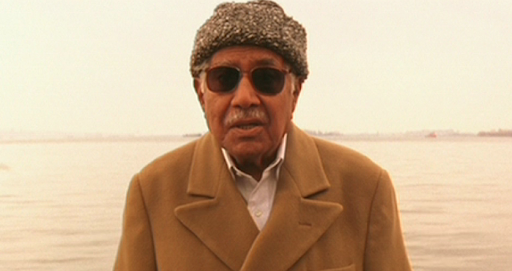

Kumar Pallana blocks the Statue of Liberty in one scene shot in Battery Park. Wes Anderson did not want any recognizable landmarks to appear in his storybook version of New York. Image: Movie Mezzanine.

Landmarks, however, are decidedly absent from Anderson’s New York. In one scene filmed in Battery Park, Anderson carefully positioned actor Kumar Pallana in front of the Statue of Liberty so the monument wouldn’t show up in the shot. Gene Hackman, who plays the charmingly roguish title character, was confused by this, according to Anderson’s former assistant Will Sweeney, asking why they were even there if not to film the Statue of Liberty. Anderson responded that he wanted to clearly invoke New York without the viewer, at any point, knowing exactly where they were. An idiosyncratic priority, for sure, but one that makes the movie uniquely evocative.

Most scenes in The Royal Tenenbaums were shot in or around the “house on Archer Avenue,” a magnificent Victorian Brownstone that is really located near Convent Avenue and 144th Street in Harlem.

“At the time I was very adamant that this would be a real place and that we have to make it a real place,” Wes Anderson explained to Matt Zoller Seitz in Seitz’s magnificent coffee table book, The Wes Anderson Collection. “It was also quite practical, I think. The roof was the real roof. It was all one place. The only cheat was with their kitchen, which was in the house next door, because this place had no windows — it was not going to work. But the rest of it’s all there.”

Each of the Tenenbaum children inhabits a room that reflects their passions. For Chaz Tenenbaum, that passion is entrepreneurship. Note the on-screen text identifying the room — a truly architectural touch. Image: WordPress.

The film crew rented the house for the duration of shooting and made careful renovations in order to capture the spirit of space, a family home that is stuffed with artifacts from childhood. The film tracks the lives of the Tenenbaum children, three former child prodigies who have grown into unhappy adults. Growing up, each Tenenbaum child was given their own floor of the house, and decades later these spaces are still decorated to reflect their childhood passions.

The director on the set of ‘The Life Aquatic.’ Image: Smith Gee Studio

The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou (2004)

Wes Anderson followed The Royal Tenenbaums with The Life Aquatic, a film that is similarly invested in themes of memory and regret. The Life Aquatic follows Steve Zissou, an eccentric oceanographer and documentarian played by Bill Murray, as he attempts to exact revenge on the “jaguar shark” that killed his friend and partner. He’s brought a film crew along for the adventure, hoping that a documentary about this Ahabian quest will revive his floundering career.

The Life Aquatic is a bit less grounded in reality than The Royal Tenenbaums. It is not just stylized but actually fantastical. It’s fitting that, for this movie, Anderson made use of constructed sets. He utilizes the cutaway “dollhouse” effect for the first time in this film to introduce Zissou’s boat, The Belafonte.

With a sauna, a laboratory, a research library, and an “observation bubble” that Zissou “thought up in a dream,” the scheme of The Belafonte tells us more about the main character’s aspirations than anything else in the film. This is very common for Anderson; his characters inhabit spaces that reflect who they wish to be.

Image: Pinterest

The Darjeeling Limited (2007)

The Darjeeling Limited is named for its principle setting, a luxury train that guides three brothers on a “spiritual journey” through India. Nathan Lee of the Village Voice put it best in his review when he described the film as as “a movie about people trapped in themselves and what it takes to get free — a movie, quite literally, about letting go of your baggage.”

As in The Royal Tenenbaums, Wes Anderson insisted on shooting Darjeeling on location in India, mostly in Jodhpur, Rajasthan, but also in various parts of Udaipur. The train itself serves as the spiritual center of the film. Tracking shots of the train in motion beautifully reflect the characters’ emerging insight that, in life, you don’t have the option of standing still.

As with The Royal Tenenbaums, Wes Anderson refused to create a studio set for the interior shots, insisting that they film inside of a real Indian train renovated to his specifications. This presented challenges, as Indian Railways were reluctant to cooperate with the headstrong American director.

Image: Mark Friedberg Design

“To this day I am not sure whether the greater achievement was the train’s design or securing the use of the train itself,” explained set designer Mark Friedberg. He admits that, at times, he was annoyed at Anderson’s insistence on shooting on a moving train but at the end realized the film could not have been done any other way.

“Wes’s confidence in his own vision is one of his finest qualities,” Friedberg explained. “The fact of actually being on the train and actually being in India gives the film its lifeblood.”

The exterior of the Grand Budapest Hotel is quite clearly a miniature model. That’s an important part of its charm. Image: National Geographic

The Grand Budapest Hotel (2014)

The Grand Budapest Hotel is a remarkable film about place, memory, and how the values of a lost era can live on through architecture.

Inspired by the writings of Stefan Zweig and his nostalgic depiction of early 20th century Vienna, the film proceeds through a series of nested narratives. The main storyline is set in the 1930s in a fictional Central European country called Zubrowka that is hemmed in by an approaching war. (This conflict is never spelled out as World War II. Anderson chooses to evoke the war indirectly, in the same way that he approached New York City in The Royal Tenenbaums.)

In the face of ominous political forces mounting in the region, the Grand Budapest Hotel — a pink and cream manor perched on a mountaintop and accessible by funicular — is an oasis of refinement. This is thanks to the careful work of master concierge, Monsieur Gustave, played by Ralph Fiennes, who oversees the hotel’s operations with pride and panache.

Model of the Grand Budapest Hotel. Image: Smith Gee Studio.

M. Gustave has an infectious elegance that at first seems campy, but over time is shown to be an ennobling reflection of his individuality. He represents the liberal values that totalitarian movements, both fascist and communist, would seek to stamp out in the ensuing decades.

Given the fact that the hotel is primarily a symbol of Monsieur Gustave’s humane way of seeing the world, it is fitting that it is depicted more as an idea than reality. The exterior shots of the hotel are a miniature model and no effort is made to conceal this fact. Many of the interior shots of the hotel, including those of the grand lobby, were taken in the vacant Görlitz Department Store, a palatial Art Nouveau structure built in 1929.

While most of the film showcases the Grand Budapest in its prime before the war, a few take place in the 1960s, when the furnishings have become drab and the exterior covered in raw concrete. All of the delicacy and whimsy have been lost as contemporary tastes have moved toward the utilitarian and (implicitly) collectivist values of the new regime.

By the 1960s, the Grand Budapest had lost its lustre. Image: Ultra Swank

With The Grand Budapest Hotel, Wes Anderson comes close to proposing a theory of architecture. For him, built spaces come to life when they reflect the ideals, aspirations and longings of the individual. This is true of the bedrooms of the Tenenbaum children, the lovingly organized bookshelves in the Belafonte library, and even in the ramshackle luxury of the Darjeeling Limited, a vehicle that promises adventure. It is especially true of the Grand Budapest Hotel, a faded monument to a past era that is imagined to have been both kinder and more stylish than the present.

Meticulous almost to the point of self-parody, Anderson’s sets embody an ethos of individualism. Not the rugged kind one associates with the American frontier, but a delicate individualism that affirms the curatorial instinct.

“You see, there are still faint glimmers of civilization left in this barbaric slaughterhouse that was once known as humanity,” M. Gustave tells his protégé, a young lobby boy named Zero, mid-way through the film. He adds that it is the mission of the Grand Budapest to uphold these civilized values in the face of encroaching barbarism, but then cuts himself short and mutters “ah, fuck it.” But no one watching believes he’s taken back the sentiment. No, it’s the heavy-handed rhetoric he rejects. M. Gustave, like the director who created him, prefers a light touch.

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.