Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter

If the Modernist movement could be epitomized in a single phrase, many would choose Mies van der Rohe’s succinct utterance, “less is more.” Three authoritative words, three stern syllables: The slogan came to embody the very architectural language it engendered, spawning a whole generation of architects who sought to strip back buildings to their bare essentials.

Mies and many of his Modernist peers advocated the abolition of the superfluous, arguing that ornamentation was a distraction from the beauty of structural rationality, or — worse still — an unethical symbol of extravagance.

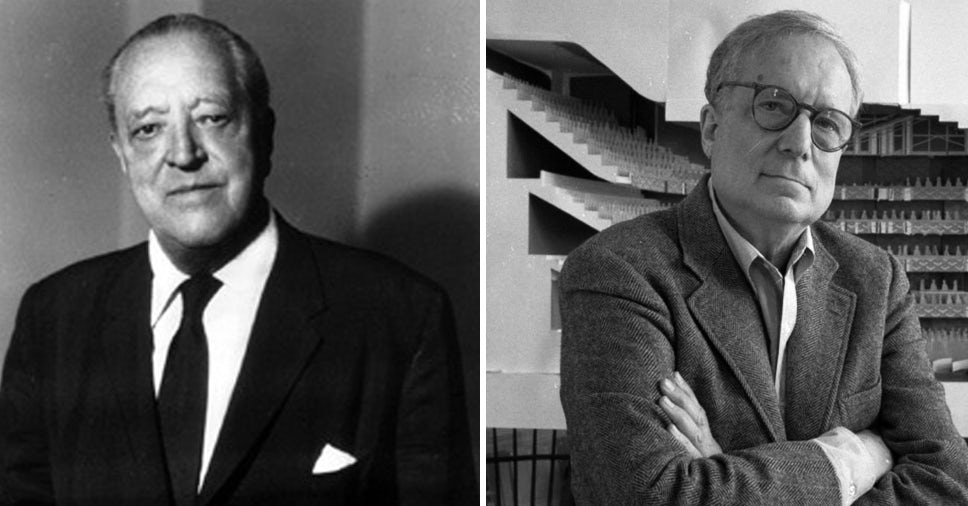

Left: Mies van der Rohe, image via Wikipedia; right: Robert Venturi, image via Alchetron

Of course, as with any ideological action, there is a reaction, and this is where American architect Robert Venturi came in. Together with his wife Denise Scott Brown, the late Robert Venturi strove to rewrite the book (sometimes quite literally) on modern architectural design, challenging the principles of the Modernist movement with experimentation and witty provocation.

Venturi pinpointed Mies’ sound bite as a key source of influence and countered with his own, simultaneously playful and cutting in its candor: “Less is a bore.”

Venturi’s instantly memorable quote — its fame perhaps only surpassed by Mies’ oxymoronic original — became the mantra for an entire architectural movement. Postmodernism ushered in an age of warmer architecture, buildings full of character that displayed a greater sensitivity toward context, urban landscapes ingrained with more humor and humility than the earnest monuments of 20th-century Modernism.

Vanna Venturi House by Robert Venturi, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; image via Wikipedia

For Venturi, this meant taking the shackles off, designing buildings that did not conform to the established rules of the Modernist manifesto. His first commission, a house for his mother Vanna Venturi, embraced this line of thinking, deliberately contradicting the formal language of Mies and more: A pitched roof was proposed in place of a flat roof; solid walls were chosen over glass; a purely ornamental appliqué arch was made the centerpiece of the front façade, referencing Mannerist rather than Modernist sentiments.

Venturi argued his position with books as well as with buildings, summarizing the Postmodernist polemic in Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture, published shortly after the Vanna Venturi House was completed. “Architects can no longer afford to be intimidated by the puritanically moral language of orthodox Modern architecture,” asserted Venturi. “I like elements which are hybrid rather than ‘pure,’ compromising rather than ‘clear,’ distorted rather than ‘straightforward.’ … I am for messy vitality over obvious unity. I include the non sequitur and proclaim duality.”

The Portland Building by Michael Graves, Portland, Oregon; image via camknows

And yet, the Postmodernist movement is widely regarded by many — particularly within the realm of practicing architects — as a failure of the highest order. Many of its buildings are regarded as ugly, with Michael Graves’ gargantuan Portland Building frequently emerging near the top of lists chronicling the world’s most despised buildings. Critics of Postmodernist architects argue that they are peddlers of pastiche, producing buildings defined by ill proportions and hideously kitsch details.

Venturi would undoubtedly laugh at such accusations, which display the same lack of humor and open-mindedness that Modernist architecture itself entails. Does architecture really need to adhere to such a narrow set of rules pertaining to composition, structure, color and texture? Venturi embraced the visceral power of design, conceiving buildings that — while frequently flying in the face of rationalism — would never fail to bring a smile to people’s faces. For him, this was the architecture of gentle anarchy, of free-spirited optimism, of unbridled joy.

Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown; image via WTTW

Returning to those polarizing quotes, editor of Archiobjects Luca Onniboni believes that no single mantra should drive every design decision of an architect. “Both sentences are slogans,” declares Onniboni, “and architecture should not be made of slogans, nor should these slogans be taken as holy words.”

Despite this truth, the eternal debate between Modernism and Postmodernism will no doubt continue for many decades to come — a fact that would only delight the late Venturi, the perennial devil’s advocate of architecture.

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter