The “Landscape of Traces” design concept envisions past transformations on the site as historical imprints or urban traces to be revealed to the public. Archaeological reconstruction is meaningless and impossible as part or most historical remains had already been permanently dug up to make way for train tunnels under the site. On the other hand, there exist no precise information from which to reconstruct.

Architizer chatted with Grace Cheung AIA , Principal Architect at XRANGE Architects to learn more about the Landscape Of Traces project.

© XRANGE Architects

What inspired the initial concept for your design?

Over the past century, there had been many “versions” of the site. An industrial service site, constructions were mostly done in utilitarian and haphazard ways. As an artillery factory and later a railway hub, the site’s insouciant past of politics, war, industry and urban growth is what draws historians, rail fanatics, and citizens to its grounds.

Realizing this cacophony of historical buildings and elements on site represents many different scales, styles and timeline, any “tabula rasa” design approach would be detrimental to the spirit of the place; also it would not be possible or sensible to make an overarching or “clean” statement from this tangle of emotions and memories. Therefore, we decided to let the historical traces guide the design concept instead. By taking the historical imprints as they are, we came up with the concept of Landscape of Traces.

© XRANGE Architects

What do you believe is the most unique or ‘standout’ component of the project?

The “blurred”, “gradient fade’ and “fuzzy edges” design language of the landscape design, which was our strategy for approximating the historical traces without claiming absolute positions. With only rudimentary maps and records available, archeological reconstruction is meaningless and impossible as part or most historical remains were permanently dug out either during urban changes or modern subway constructions.

On the other hand we wanted to tell the story of these historical imprints in a kind of light and abstract way. The point is to incite curiosity and a sense of knowing imagination rather than providing critical proof of geolocation for archeology. The historical imprints are a part of Taipei’s collective memory, and like memories, they are physical and intangible at the same time.

© XRANGE Architects

What was the greatest design challenge you faced during the project, and how did you navigate it?

The greatest challenge was to convince all stakeholders of our design approach. We took aspects of the site that is considered rather unheroic and informal, and endeavored to transform that into an urban identity for the museum, and to create a unique place for the people of Taipei. Over the course of the project, there were even viewpoints that doubted the meaning or necessity of the design; the design was at times questioned as being “surface articulation” which required a fair bit of complexity to construct. As the project processed, dissenting voices became either the minority or that they fizzled out eventually. We were very committed in our mission to bring this forgotten aspect of the museum park to the fore, perseverance and patience were essential through and through, and as with all projects, a little bit of timing and luck helped.

© XRANGE Architects

How did the context of your project — environmental, social or cultural — influence your design?

The project was conceived entirely from the environmental, social and cultural history of the site. Developed from historical records, the Landscape of Traces design cannot be transposed anywhere else, not even to other parts of Taipei, as it is that true and specific to the location.

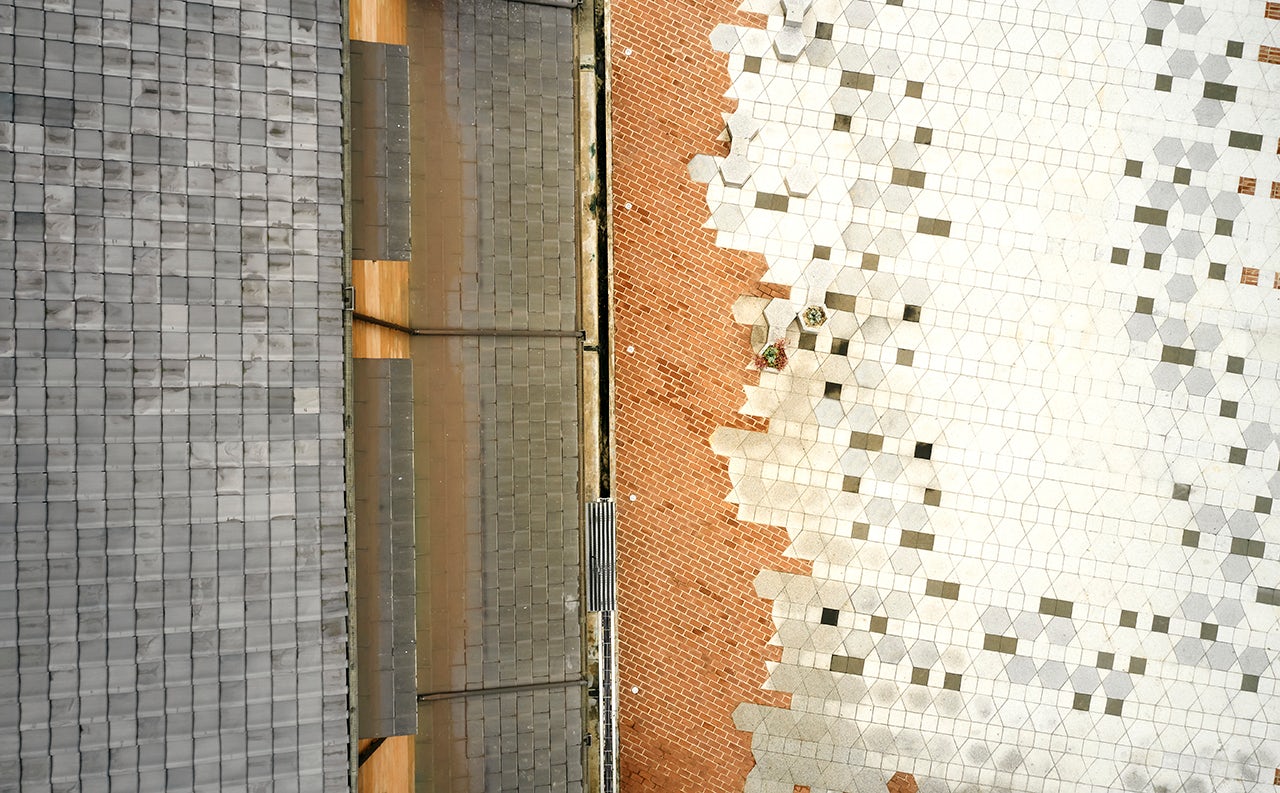

The landscape design provides a real, life-sized reference to the exhibition content within the museum building, which covered the history of the site. The design also “codified” the historical traces in a very simple and direct way, such as using red bricks to mark where wooden canopied walkways were, grey granite as building outlines or red granite as where railway tracks were, etc.

© XRANGE Architects

What drove the selection of materials used in the project?

We used reclaimed black ceramic roof tiles from the site in parts of the paving as patterns. In the beginning, we proposed the use of actual historical remains such as stones and wood recovered on site. This idea proved to be too complex to execute, the museum decided to collect those for indoor display, and any further discovery of unearthed remnants would have to go through historical status review and all site work must halt on site until such reviews are done. We would have loved to interweave these unearthed elements into the design. In the end, only the reclaimed black ceramic roof tiles were suitable to reuse.

© XRANGE Architects

What is your favorite detail in the project and why?

The “clashing” of different brick patterns with the overlay of the traces of railway tracks demolished in the 20s, running head on into the wooden historical structures. This really captures the spirit of change as witnessed on the site, as all those elements were from different timeline. Here, they collide and crystalized this sense of changing times and urban transformations.

© XRANGE Architects

How have your clients responded to the finished project?

We had worked through 4 museum director tenure over the course of the project! The current director intends to acquire our design sketches as permanent collection to the Taiwan architectural archive, part of an ongoing national project towards the establishment of an architectural museum.

© XRANGE Architects

© XRANGE Architects

© XRANGE Architects

Please list any team members and consultants you’d like to include in the credits

Team Members: Grace Cheung, Royce Hong, Emily Lin, Peihsuan Hsu, Sonia Pan, Joey Hsieh, Jason Chen, Norince Lee, Haochun Hung, Miriam Park, Soledad Moreno Velasco, Changchun Tsao, Yourue Wang

Lighting Design : Unolai Lighting Design & Associates

Landscape Of Traces

Landscape Of Traces