Two projects, unveiled on the same day last week, shed light on some of the issues that contemporary architects face, from the beginning of a project to the end. They couldn’t be more high-profile yet they also couldn’t be more different in their origins and public reception. But something tells us that both projects are likely constrained by political and physical conditions that dictated nearly everything about each one, from the materials and form to their possible construction and future use.

Image courtesy Morphosis Architects

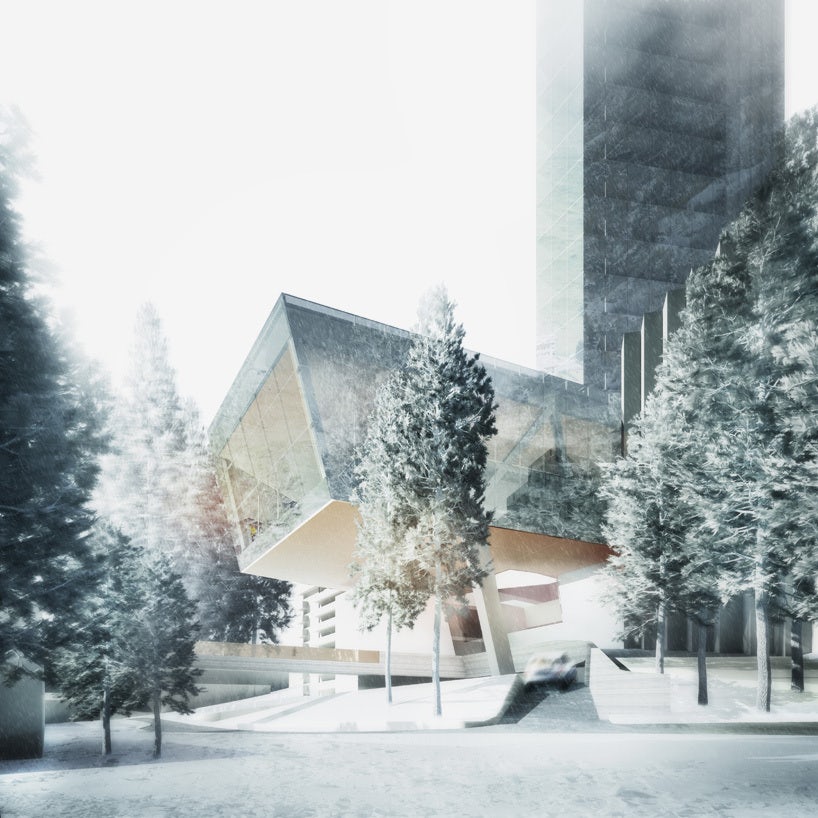

The Vals Therme Hotel and London’s 2015 Serpentine Pavilion both gained considerable attention upon their release. In Vals, Morphosis designed a tower that is poised to be the tallest in Europe, a fact that sounds strange only considering the context: Vals is a remote mountain village in Switzerland’s Alps, accessible only by a windy mountain road. It is not just any small remote town, however — it is the home of Peter Zumthor’s masterpiece Vals Therme spa.

Intriguing though the juxtaposition may be, the tower makes no sense in this context. There has been a wave of outrage and backlash against the 1,250-foot skyscraper hotel in the town of 1,000, most of it directed at Morphosis’s Pritzker-winning principal Thom Mayne. The Guardian‘s Olly Wainwright called it a “gigantic mirror-clad middle finger.” Internet commenters responded in kind, as per usual.

Image courtesy Morphosis Architects

Yet the outrage seems misdirected: If every architect in the world were to design a super-tall skyscraper in such a physically daunting (secluded mountain range) and culturally awkward (architectural mecca) context, is there any suitable solution? It seems that Morphosis’s hands are tied. The minimalist mirrored tower actually does the opposite of what many critics are charging. It has been called a middle finger to its context and possibly the world. But if it is a middle finger, it’s not Mayne’s — it is the client’s.

Image courtesy Morphosis Architects

The story goes back to 2012 when a consortium that included Zumthor lost out on a bid to purchase the spa from the local government. The winner of this fight, Remo Stoffel, plans to develop the 7132 Hotel. As part of the scheme, 7132 shortlisted architects including Steven Holl, Morphosis, and six other firms, only to bypass the international jury and appoint Morphosis. Given the context of the hotel and the brief, it seems the architects have at least tried to minimize the impact, indicating at least an awareness of the context:

“A minimalist act that reiterates the site and offers to the viewer a mirrored, refracted perspective of the landscape… the tower’s reflective skin and slender profile camouflage with the landscape, abstracting and displacing the valley and sky.”

While the success of the strategy is debatable and likely impossible to determine based on the unrealistic renderings, it is at least the right attitude. What would have been more acceptable? A contextual, wooden skyscraper? Nothing short of an invisible building would really work in this valley, so perhaps Morphosis has produced the least of all evils? Before we blame the architect, we should consider all of the forces behind this proposal.

Image courtesy Selgascano.

Should the architects made a statement and refused the project? That brings us to our second recently unveiled project, the 2015 Serpentine Pavilion in London. The 15th edition of the annual temporary structure in Kensington Gardens has been awarded to Spanish firm Selgascano, in keeping with the curators Hans Ulrich Obrist and Julia Peyton-Jones’s penchant for selecting younger practices for the commission rather than mega-firms.

This year’s design is a series of colorful plastic tunnels made of fabric and webbing. Unfortunately, the project is hampered by its unexpectedly low budget, producing what Wainwright rightly questions as potentially disastrous: “From this image, there’s a danger it could look like a half-baked student project, hashed together on a shoestring.” The architects were forced to change their design from the initial proposal as they realized the limits of the resources they had to work with. Luckily, the Spanish firm has, in the past, produced brightly colored, vibrant architecture from everyday materials with great success.

Image courtesy Selgascano.

The contrast between the Serpentine Pavilion and Vals Therme reveals the double bind that architects face today: Take on outrageous projects like ultra-high-end housing or hotels, or face the inversely restrictive typology of cultural commissions or similarly underfunded social design projects. This dichotomy puts architects in an awkward position. Often the job of the designer is to make something out of nothing: extremely inexpensive or otherwise compromised designs that satisfy the client. It is not the architect who is destroying the beautiful, unspoiled, or culturally diverse area, it is the shadowy developer, an eminence grisé if there ever was one. The question is whether there is a middle ground between these rocks and hard places?

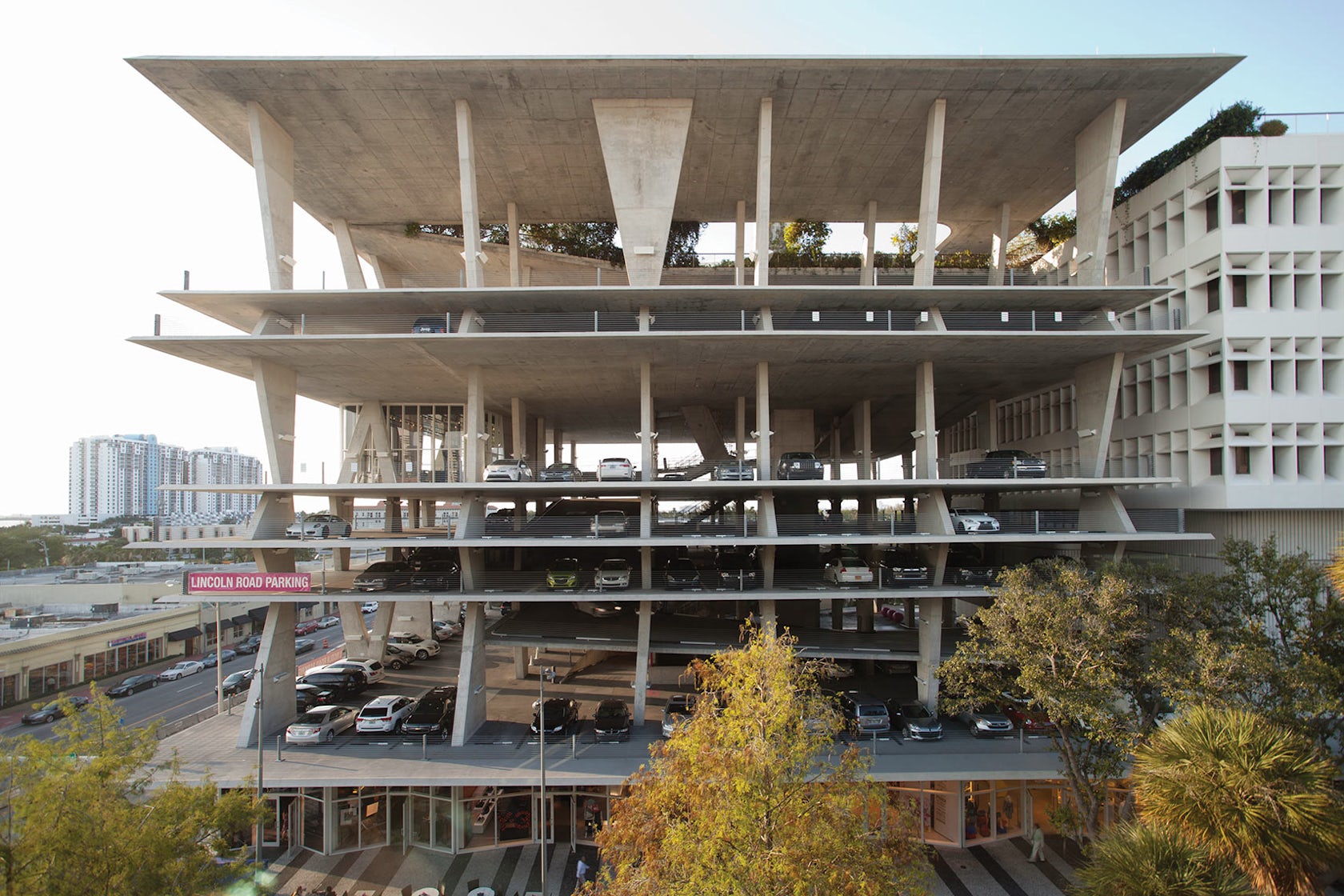

One way the profession can help itself is for critics to stop lambasting it in publications like the New York Times. Martin Pederson and Steven Bingler saying that the entire profession is out-of-touch based on a handful of designs and the public’s questioning of them. (I’m sure the authors know that flat roofs are not truly flat, right?) Rather than rehash post-modern clichés about out-of-touch architecture, let’s celebrate the places where design has been successful, so that the people who have the money to commission architecture see the potential of architecture to perform. We could redirect the critique toward clients that value-engineer buildings to death — but better yet, we can start to advocate for design’s value to inspire clients who can get it right, like Miami’s Robert Wennett, who received the Architizer A+Patron of the Year award in 2014 for his creative commission of Swiss power-firm Herzog + de Meuron to design 1111 Lincoln Rd, a parking garage. It is those kind of stories that will drive the real people with power (clients) to change, not bemoaning Morphosis for taking on a job that had an impossible task as a brief.