Denmark’s a prison.

– Hamlet, Act 2, Scene 2

Every autumn, when I hand out copies of Hamlet to my AP English Literature class, I warn my students that the play is a trap. Some passages are crystal clear, especially the soliloquies in which Prince Hamlet speaks of himself and his circumstances with startling depth, as if he is interpreting the play for us as we watch. And yet so much of the play is shrouded in mystery. Hamlet does not, in the end, understand himself — he does not know why he does what he does or feels what he feels. And neither, of course, does the audience.

No matter how many times we watch or read the play, basic questions remain unresolved. Did Hamlet ever really love Ophelia? Does he really want to be king, or is he, at some level, relieved that his uncle “popp’d in between the election and [his] hopes”? And why oh why does he delay his revenge? (The ruthlessness with which he disposes of Polonius, Rosencrantz, and Guildenstern fatally undermines the theory that he feels some kind of moral qualm about violence.)

This teasing alternation of blindness and insight, darkness and light, might be the secret of the play’s enduring popularity. For readers, the play is a pleasurable trap because it lures them into the vortex of an endless mystery. But for Hamlet it is, as he says, a prison — a reality he hates and cannot escape.

Eugène Delacroix, “Hamlet and His Mother,” 1849. From the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

The theme of confinement is thus fundamental to the play. Hamlet would not have its trademark mood of paranoia if the prince were free to move about the castle, or take off and enjoy a day trip in a nearby town. If he were free in this way, perhaps he would not go mad. (And he does go mad — he might just be pretending in the beginning, but by the time he confronts Ophelia in Act 3, the mask has eaten the face).

Technically, of course, Hamlet is not imprisoned — his “uncle-father and aunt-mother” simply request that he not return to school in Wittenberg, they don’t forbid it — but he knows the score. He is being watched. His home has become a panopticon. Everyone he once trusted, from his girlfriend, Ophelia, to his buddies Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, might be spies acting under Polonius, the king’s chief intelligence officer. Hamlet even keeps his best friend, Horatio, at arm’s length, perhaps fearing that he too could be a spy.

Grasping the setting of Hamlet is essential to understanding the prince’s predicament. The play does not just take place in a royal court, but in a fortified castle that is mobilizing for war. It is a space that is at once public and enclosed, an environment for both spectacle and surveillance. And luckily for Shakespeare enthusiasts, it is also a real place that you can visit today.

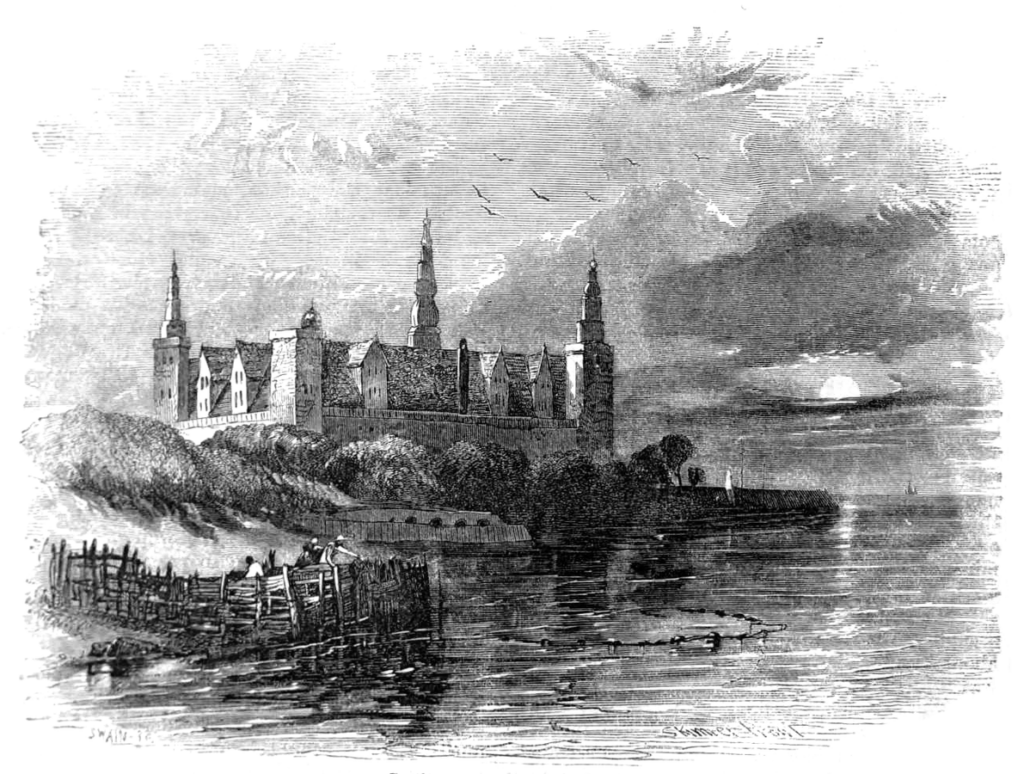

Kronborg Castle, a.k.a. Castle of Elsinore, from an 1862 travel article. Wood engraving, drawn by John Skinner Prout and engraved by the workshop of Joseph Swain. Once a Week magazine, volume 7, page 54. via Wikimedia Commons

So much about Hamlet snapped into place for me this month when I visited Kronborg, the Danish castle that served as the model for Elsinore, which is what the castle is called in the play. The name Elsinore is an Anglicized form of Helsingor, the town where Kronborg can be found, perched on the eastern shore of the village. On clear days, Sweden is visible across the water. This was hotly disputed territory in the 16th century, when the current castle was built by Frederick II. Cannons face out from above the castle walls, just as they do in the play as the kingdom arms itself against an anticipated attack from Norway. The looming threat of invasion is built into the form of the castle, just as it is the form of the play.

To reach Kronborg, visitors need to traverse a series of moats. (The “glassy stream” where Ophelia drowns?) The fortifications are still intimidating — even now that the castle is merely a tourist attraction. If it wasn’t for the ornate spires, it would very much resemble a “prison,” just as Hamlet describes.

Kronborg is fortified with moats, walls, and cannons. Photo by David Castor, via Wikimedia Commons.

Inside the complex, everything is organized around a square interior courtyard, certainly the setting of Hamlet’s famous confrontation with Ophelia, in which her father, Polonius, callously uses her as bait in a foolish scheme to divine the prince’s mental state. The chapel where the king, in prayer, confesses to his brother’s murder is located directly off this courtyard. It is the only part of the castle complex that still contains the original Renaissance furnishings.

To reach other famous settings of the play, such as the banquet hall and the queen’s bedchamber, one must walk up a claustrophobic spiral staircase. Along the staircase, locked doors suggest passageways for attendants and spies.

I felt a chill as I peered into the queen’s bedchamber, which my guide informed me is more spacious than usual for a Renaissance castle. I felt I could “see” the dreadful action of Act 3 Scene 4 take place here before my eyes: Hamlet’s frothing attacks on his mother, words she says enter her ears “like daggers”; the fireplace where the ghost of King Hamlet appears for the second time; the shadowy bed curtains that Hamlet stabs with his rapier, killing Polonius instead of his intended target, the usurper king. I couldn’t help but envision blood pooling on the floor underneath the curtains — and then dripping along the floor as Hamlet drags the body to its hiding place in the stairwell.

The queen’s bedchamber. Richard Mortel from Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Interior, Kronborg Castle (1) (35563097444), CC BY 2.0

This all might sound very fanciful, the ravings of a Hamlet obsessive eager to read more into the castle than is really there. After all, Shakespeare never visited Kronborg. Isn’t it a stretch to say that the play “takes place” here in any important sense?

In fact, Shakespeare likely knew a great deal about Kronborg. Most Londoners would have known of the castle by reputation, as sailors who traveled into Denmark spread word of its magnificence. But Shakespeare knew even more than this. Rasmus Baker-Andersen, a tour guide at Kronborg, informed me that two actors from Shakepeare’s company, Lord Chamberlain’s Men, performed here in 1585. Plays were performed right in the banquet hall — the very place where Hamlet confronts Laertes in his fatal duel at the play’s conclusion — so Shakespeare’s acquaintances would have had a very intimate look at court life inside the castle.

Cannons at Kronborg via Wikimedia Commons

The best evidence that these actors spoke to Shakespeare about their experience can be seen in the play itself. In Act 1, the king is shown to fire cannons in celebration every time he takes a drink of wine. Hamlet speaks of this practice critically, ironically describing it as a “custom more honor’d in the breach than the observance.” Nevertheless, this was a real custom that Frederik II followed, something Shakespeare’s actors would have witnessed first hand. Perhaps they, like Hamlet, found it obnoxious. In any event, its inclusion in the play is not a coincidence. Baker-Andersen confirmed that Frederik II is the only monarch known to have fired ceremonial cannons while drinking.

The more time one spends in Kronborg, the more plausible it seems that the castle might have actually inspired the play. Who knows? Perhaps the poet was enraptured by his colleagues’ stories about this opulent yet fearsome palace that looks over the icy Øresund. One can picture him late at night, eyes downcast, crafting scenes to fit the setting that loomed so grandly in his mind.

Cover image: Kronborg, Artico2, CC BY-SA 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons