Architizer’s newest print publication is available for pre-order! How to Visualize Architecture is an educational guide designed to help you master the craft of architectural storytelling and visual communication. Secure your copy today.

Founded in 2008 in Beijing, Vector Architects has distinguished itself by embracing a philosophy of integrating architecture with its environment, prioritizing logic and restraint over grandiosity. Under Dong Gong’s visionary leadership, the firm has charted a course focused on uncovering subtle interrelationships between program and place, using spatial structure to enhance the perception of light, breeze, material and time. In an era of rapid development, their work evokes tranquility, creating spaces that invite users to connect with their surroundings and reflect on their place within the physical world. For their profound built and discursive contributions to architecture, Architizer is proud to honor Vector Architects with this year’s Leadership in Design Award.

Projects like the Seashore Chapel and the Jingyang Camphor Court showcase Vector Architects’ luminous yet grounded aesthetic. Taken as a whole, their oeuvre has defined a contemporary architectural language that honors local context and tradition in more subtle and poetic ways, encouraging users to be radically in tune with their present moment and inspiring other architects to revisit the fundamentals of architecture for the future. The firm also emphasizes the integral connection between architecture and construction. Setting an example by repositioning architecture’s relationship to its societal context, this belief informs every phase of their projects: from researching, experimenting and manufacturing materials to prototyping and refining joints and details and on-site supervision and coordination.

Dong’s contributions, however, extend beyond built work. Through speaking engagements and publications, he has become an influential voice, encouraging architects worldwide to reconsider architectures’ traditional boundaries. Likewise, Dong’s design philosophies are guiding the next generation of architects — through his teaching in China, at Tsinghua University and Central Academy of Fine Arts, and abroad, at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign the Polytechnic University of Turin. This dedication to the craft and broader architectural discourse exemplifies the leadership and vision for which Vector Architects is being celebrated.

The following interview with Dong was conducted in honor of this prestigious award, which be presented at the A+Awards Gala in Chengdu this November. Musing on the firm’s architectural ethos, he elaborates on how Vector Architects approach their role as mediators between architecture and the site, balancing form with feeling and the practical with the poetic.

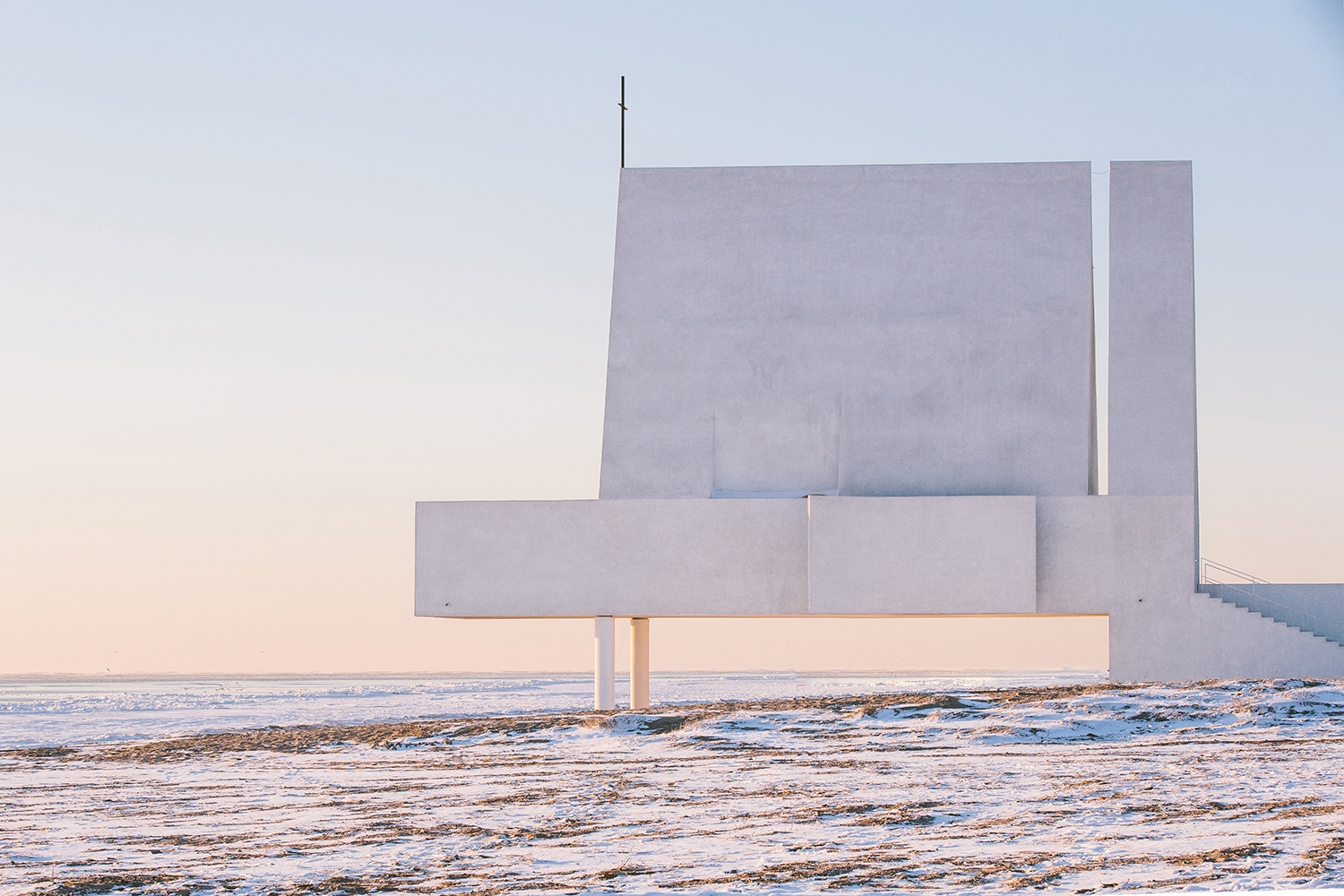

Seashore Chapel by Vector Architects, Qinhuangdao, China

Hannah Feniak: Tell us a little about your story — how did you get started? How did your firm grow?

Dong Gong: The core philosophy of Vector Architects is grounded in sincerity. We tackle architectural challenges by thoughtfully addressing social, environmental and cultural dimensions. Rather than relying on rigid or formulaic approaches, we embrace the transformative potential of space. Ultimately, I believe that solving architectural problems should evoke a meaningful emotional response in those who experience the design.

As the firm is centered around me, cultivating this philosophy within a team of 30 to 40 young architects from diverse backgrounds takes time. For instance, we place great importance on construction quality. We assign on-site architects to every project so they can gradually understand Vector Architects’ standards for precision and quality. This daily training helps them develop the resilience needed to navigate both creative challenges and intricate details.

The most significant change has been our growth in staff. When Vector Architects first started, it was just two or three of us working around a table in a residential building near Sanyuan Bridge. Now, we have nearly 30 architects and around 40 with interns. In the beginning, I attempted to apply management strategies from my experience in the U.S., but cultural and contextual differences led to frustration. In the U.S., detailed drawings are finalized before construction due to ample design time. In contrast, in China, design timelines are much shorter and changes often occur during construction. This realization prompted me to shift my focus from perfecting initial design drawings to refining project details through long-term tracking.

In recent years, we’ve also adapted to evolving environmental trends. The Seashore Library (2015) reflected the real estate and commercial dynamics of that time. However, as China has moved away from mass construction to focus on preserving historical sites and urban spaces, urban renewal projects have become increasingly common. Vector Architects has embraced this shift, respecting existing conditions while creating innovative ways to revitalize spaces, blending the old with the new to enhance the quality of life.

Seashore Library by Vector Architects, Qinhuangdao, China

Looking back, which of your projects do you feel was the most significant to the firm’s development and why? [You can pick more than one!]

For many years, Vector Architects has upheld the belief that architecture holds the power to reveal the hidden energy within a site. By strategically utilizing design elements such as space, materials, light and scale, we aim to bring the essence of the place to life, making it something people tangibly experience. The Seashore Library, Captain’s House and Yangshuo Sugarhouse Hotel represent key stages in our architectural journey, each attempting to uncover and highlight the unique characteristics of their respective locations. Through architecture, we sought to create a coherent and meaningful narrative.

At the Seashore Library, we envisioned the main reading space as a “grandstand” with gradually rising steps, allowing visitors to enjoy uninterrupted views of the sea from various levels. A large horizontal window frames the sea, making it the central focus of the space. So the sea becomes a dynamic stage, constantly shifting with the seasons and the passage of time, becoming an integral part of the library.

When the Seashore Library was completed in 2015, it was dubbed “China’s loneliest library,” and its influence has only grown. Over time, this building has transcended the traditional boundaries of architecture, generating an even greater impact. The library has evolved into a spatial phenomenon, which was not easily replicable. Fueled by societal progress, material accumulation and a collective yearning for deeper meaning, it emerged as a powerful experience rooted in a particular time. From a communicative perspective, the name “Lonely Library” and the solitude it evokes struck a deep chord, penetrating through the layers of societal noise and resonating with the emotional state of the era.

Renovation of the Captain’s House by Vector Architects, Fuzhou, China

The Captain’s House, located in a small coastal village in Fujian, holds a unique position due to its setting. Although the renovation was initially commissioned by a TV show, the project integrated the real-life needs of the family, which gave it deeper significance for me. In today’s real estate market, communication between users and designers is often fragmented, as market pressures make it difficult to foster meaningful connections. However, when designing a residence, it is essential for architects to engage with the people who will live there, understand their needs, and reflect those insights in every space.

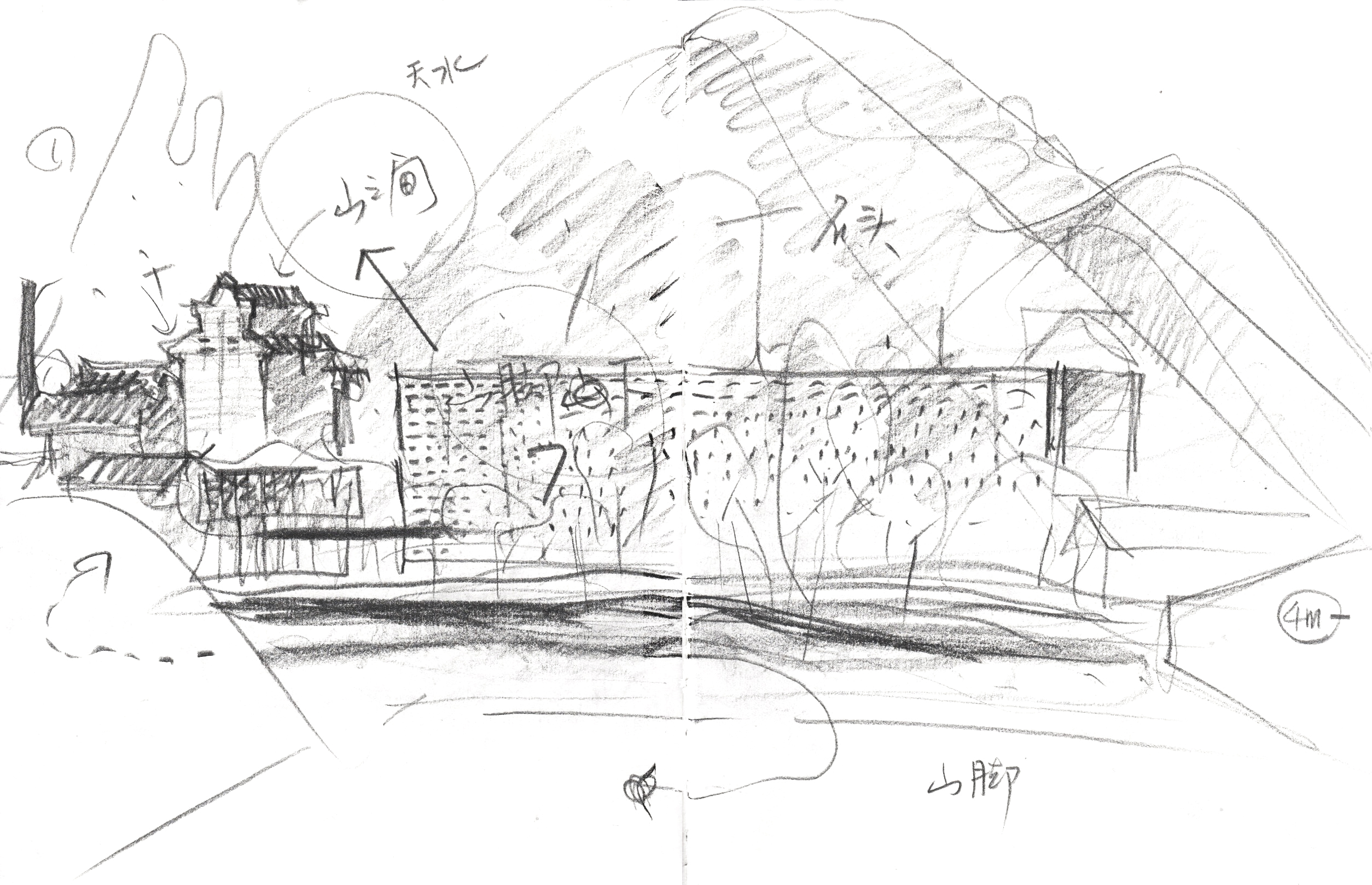

The Yangshuo Sugarhouse Hotel was once an old sugar mill, already a local landmark before its renovation. The site itself has a strong, inherent energy. Nestled in a valley by the Li River, surrounded by the striking karst mountains, the site includes the 1960s sugar mill and the industrial trusses used to transport sugarcane. In the past, sugarcane was brought in by boat along the river, processed at the mill and transported out by land.

In terms of layout, the new buildings are positioned on either side of the old sugar mill, keeping the mill and trusses as the focal point of the complex, emphasizing their memorial-like quality. The new structures are simple and restrained, designed to avoid overpowering the original architecture. Their abstract geometric forms, combined with perforated masonry walls, create a dialogue with the surrounding natural landscape.

On my first visit to the site, I was deeply moved by the contrast: the distant mountains of the Li River, with a massive industrial truss suddenly appearing in the foreground. Weathered by decades, the once-rough truss now seemed like a natural relic. In some buildings, the most valuable element is the passage of time and the history it imparts. Our interventions here were minimal—we simply added a swimming pool and made subtle adjustments to preserve the most evocative aspects of the site. Seven years later, the Sugarhouse Hotel has become a seamless part of its environment. The weathered concrete blocks, now intertwined with climbing plants, have softened over time, blending seamlessly with and enriching the landscape of the old sugar mill and its surroundings.

Yangshuo Sugarhouse Hotel by Vector Architects, Guilin, China

Your work has been hailed as a hallmark of a new school of contemporary Chinese architecture. How do you feel your firm’s unique cultural and environmental context has shaped its evolution?

Architecture is a discipline rooted in practice, where architects need to prove themselves through their work. The era of rapid urban development in the West has come to an end, and their current construction output pales in comparison to that of China. While there is increasing interest in Chinese architectural design in the West, a significant gap in understanding remains. The energy and potential within China’s architectural landscape far exceed what the West has observed or grasped.

There is a “time lag” between China and the West in addressing current challenges facing the architectural industry. We have our own urgent issues to solve, and it requires both responsibility and courage to tackle them — often in ways that are not immediately obvious. We must confront the relationship between architecture and society, be it technical or emotional. While this path may be longer, it is a deeply meaningful pursuit.

In every project, our team and I focus on striking the right balance in design, aiming for quality that is sincere, unpretentious and modest. This is a vital quality for any architect. If we think of architecture as a reflection of character, buildings should possess virtues such as humility, politeness and restraint in how they coexist with their surroundings. Just as individuals can possess deep thoughts and talents, so can architecture. Both in China and around the world, there is a growing appreciation for buildings that, instead of being overly extravagant, resonate with people through their spatial quality and integrity. Over the past decade, architectural design has witnessed a significant shift in these values.

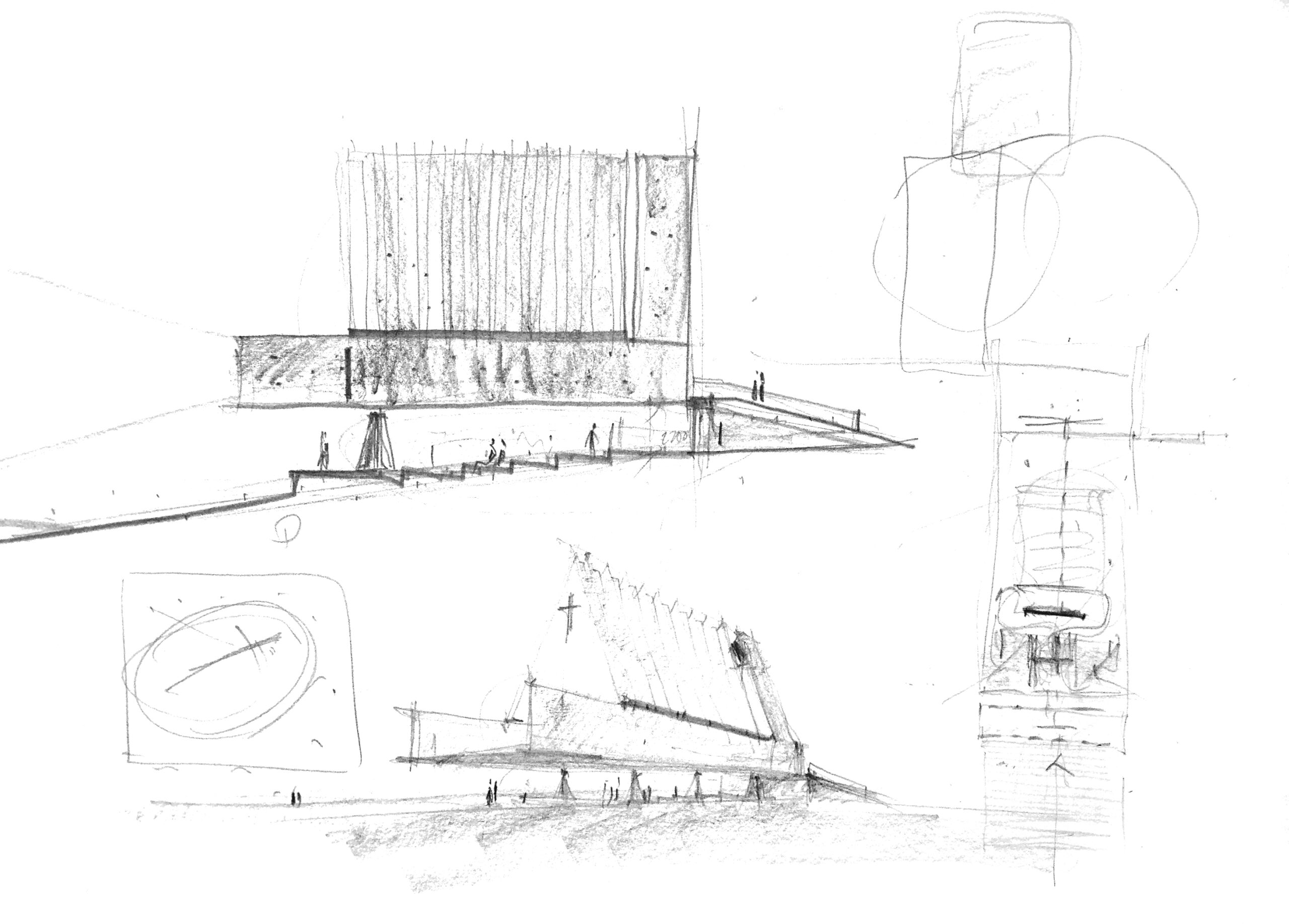

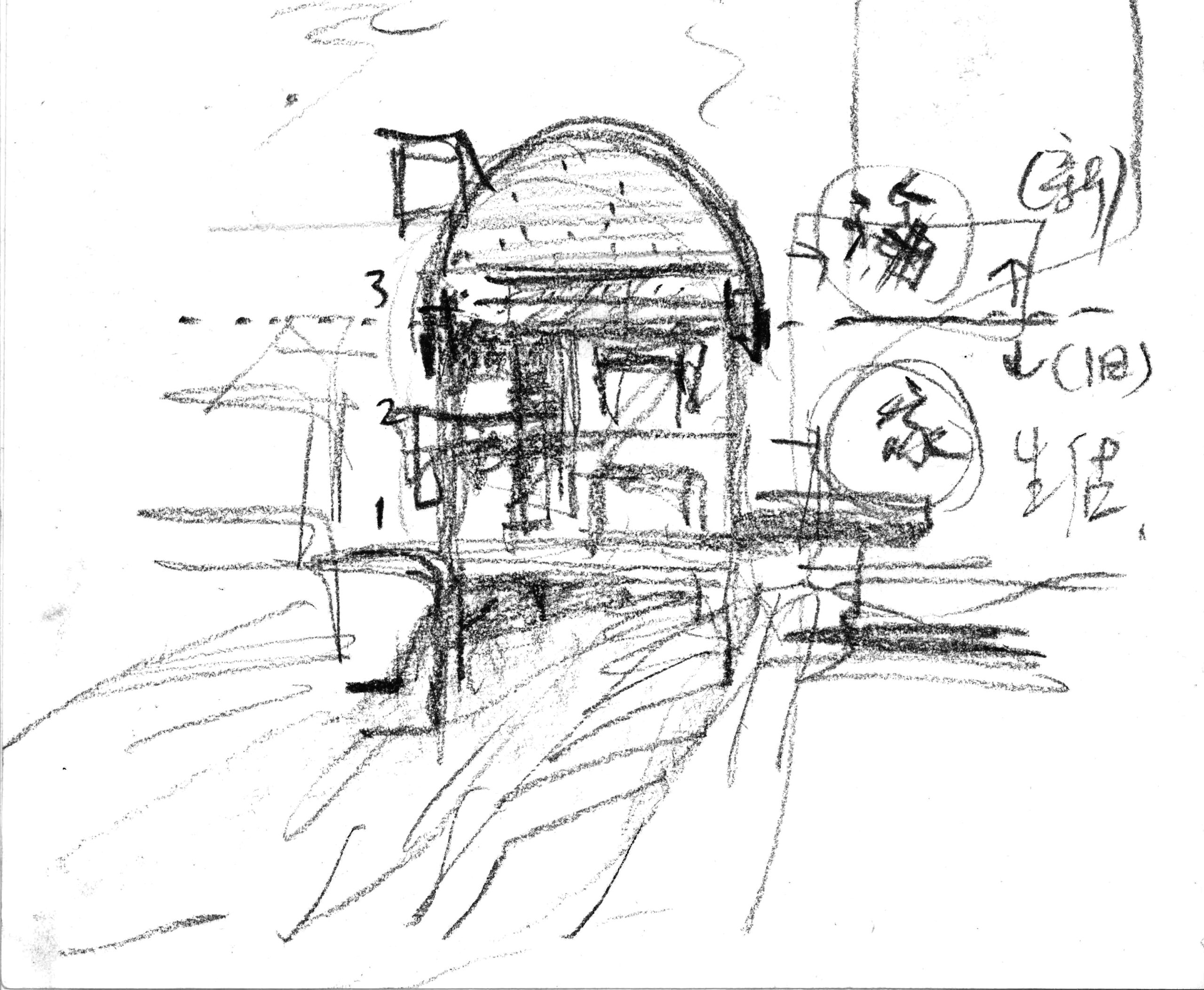

Jingyang Camphor Court by Vector Architects, Jingdezhen, China

What does winning Architizer’s Leadership in Design Award mean to you and the firm?

As China’s urbanization evolves, architecture is gradually adapting to these changes. We believe the role of architecture is shifting from being merely a symbol of power and a landmark to serving as a mediator and coordinator that engages in the collaborative development of urban and rural areas. This transition does not signify a compromise in construction quality; rather, it embodies a more humble and thoughtful approach. It allows architecture to coexist harmoniously with the social, historical and natural contexts upon which we depend, thereby fostering a more vibrant vitality.

In our seventeen years of practice at Vector Architects, we have evolved from early projects like the Shoreside Library — often described as “viral” and a “landmark” — to our recently completed Jin’yang Camphor Court in Jingdezhen. In these projects, we have made significant efforts to preserve each original tree while nurturing spaces where the old and new coexist harmoniously. We have come to realize that architecture should not impose itself forcefully or stand in opposition to its surroundings. Instead, we are exploring how architecture can sensitively and authentically respond to the site’s characteristics, becoming a more site-specific entity that resonates with its environment.

Looking ahead, we will continue to serve as mediators between architecture and the site. We aspire for architecture to restore and reinforce the “ordinary” elements of life with a benevolent approach. This does not mean that architecture relies on the site; rather, through re-delineation, negotiation and revelation, both architecture and the site evolves together to achieve a new balance. In this process, architecture actively participates in the site’s reconstruction, coexisting and iterating with the surrounding environment, reviving the essence of the “ordinary” and allowing it to shine.

This award encourages us as we hope our practices will positively influence the future trajectory of architecture.

Liyuan Foreign Language Primary School by Vector Architects, Shenzhen, China

This award reflects your powerful leadership not only in your built work, but also through speaking and teaching. If you had one piece of advice to offer the next generation of architects — specifically Chinese, or global — what would it be?

It’s about passion. Architecture is a field that demands time, experience and growth; it doesn’t change overnight like some industries. There are no shortcuts to becoming a great architect; it requires patience and continuous practice. Without passion, this journey can feel arduous and the sense of achievement may come slowly. However, if you love what you do, there’s no need to hesitate. The rewards of architecture are unique: from developing design concepts to seeing the physical structure come to life and witnessing how people interact with the spaces you’ve created — this sense of accomplishment is unparalleled.

Architects don’t just design buildings; they actively engage with society on multiple levels. From boardroom meetings with stakeholders to hands-on work at construction sites, the shift between roles is challenging, yet deeply rewarding. When your design is realized and appreciated by the people who use it, you’ll understand how profoundly impactful and distinctive the role of an architect is.

Architizer’s newest print publication is available for pre-order! How to Visualize Architecture is an educational guide designed to help you master the craft of architectural storytelling and visual communication. Secure your copy today.