Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

In Bong Joon-ho’s Academy Award winning film ‘Parasite,’ architecture isn’t silent, it speaks. Again and again, the built environment indicates where people fit into the social hierarchy — or if there is a place for them at all.

The film opens in the apartment of the Kim family, the movie’s protagonists. This is a semi-basement apartment, or banjiha, a common type of working-class residence in South Korea. “It really reflects the psyche of the Kim family,” explained Joon-ho in an interview with Architectural Digest. “You’re still half overground, so there’s this hope and this sense that you still have access to sunlight and you haven’t completely fallen to the basement yet. It’s this weird mixture of hope and this fear that you can fall even lower. I think that really corresponds to how the protagonists feel.”

An early rendering of the Kim family’s semi-basement apartment. Photo: ⓒ 2019 CJ ENM CORPORATION, BARUNSON E&A

From the first shot of the film, the viewer can see that this is an improvised living situation, a space where nothing ever feels settled. As the opening credits flash across the screen, the camera lingers over socks hanging from a light fixture that is being used as a makeshift drying rack.

In the next shot, we see the two youngest members of the Kim family, siblings Ki-jung and Ki-Woo, frantically scanning the apartment with their phones, searching for an unsecured wi-fi signal they can connect to. They eventually find service in the strange bathroom, in which the toilet is elevated on a tiled platform. Now, it seems, the bathroom will become a new communal space where the family will hang out and browse the Internet.

Park So-dam, left, and Choi Woo-shik play the two children of the Kim family. Photograph: Allstar/ Curzon/ Artificial Eye

The way the Kim family lives in their space, improvising as necessary, reflects the way they exist economically. Without stable jobs, the Kim family is forced to constantly hustle, make adjustments, and find new ways to make money. If they slow down, even for a second, it might prevent them from making ends meet.

The Kims’ stressful lifestyle is emblematic of the so-called “gig economy” that has emerged in recent years. In his now-classic 2009 book Capitalist Realism, the late theorist and blogger Mark Fisher argued that the proliferation of “gig” work in the 21st century has taken a serious psychological toll on workers worldwide.

The Kim family’s most recent “gig” is folding pizza boxes. Photograph: Allstar/ Curzon/ Artificial Eye

“To function effectively as a component of just–in-time production you must develop a capacity to respond to unforeseen events, you must learn to live in conditions of total instability, or ‘precarity’, as the ugly neologism has it,” Fisher explains. “Periods of work alternate with periods of unemployment. Typically, you find yourself employed in a series of short-term jobs, unable to plan for the future.”

This passage, like many others in the book, could have been written about the Kims.

In ‘Parasite,’ the crucial difference between the experience of the working-class and the upper-class is not opulence but stability. The only other living space that features prominently in the film is a gleaming modern estate enclosed by concrete walls. It belongs to the Park family, for whom the Kims’ college-aged son, Ki-Woo, goes to work as an English tutor. (With fabricated credentials, of course; like his other family members, Ki-Woo is adept at hustling, or doing what he needs to survive).

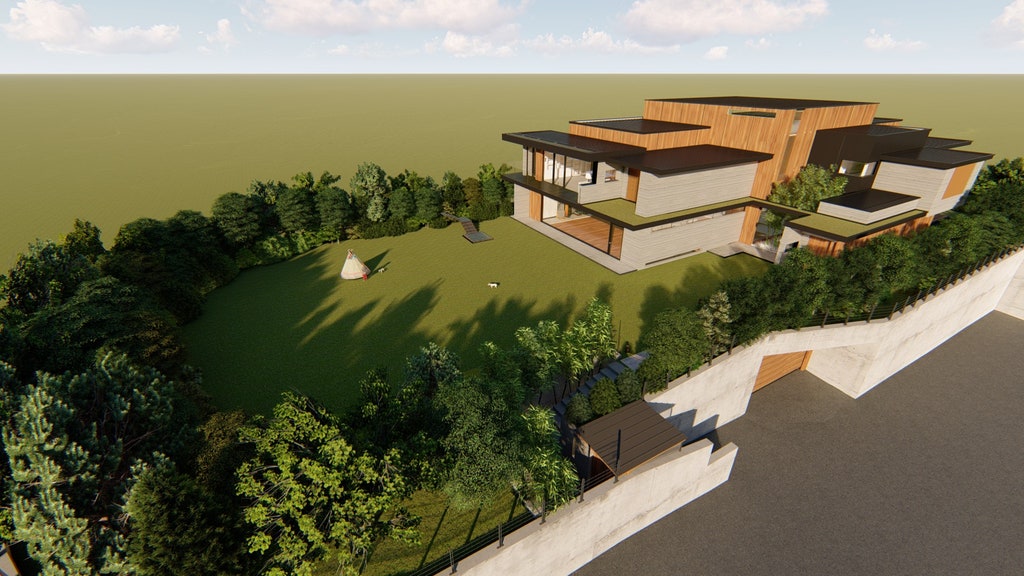

The residence of the wealthy Park family is said to have been built by a famous architect. This is an early rendering developed by production designer Lee Ha Jun. Photo: ⓒ 2019 CJ ENM CORPORATION, BARUNSON E&A

Much has been written about the Parks’ gorgeous house, which is said in the film to have been designed by a famous architect named Namgoong Heonja. The space is so convincing that many viewers of the film assumed it was a real house, an architectural marvel. However, it is actually a series of sets designed by Lee Ha Jun, the film’s production designer.

“Bong left it all to me in terms of its architectural style,” Lee explained in an interview with Dezeen. “He showed me a simple floor plan which he sketched whilst writing the script.” Instead of sticking to one architectural style, Lee took inspiration from multiple homes that had a minimalist design. The key element he wanted to capture was “great space arrangement.”

The sets were designed to convey “great space arrangement” according to proudction designer Lee Ha Jun. Photo: ⓒ 2019 CJ ENM CORPORATION, BARUNSON E&A

The fact that the Parks’ house was supposedly designed by a famous architect is a significant detail. As soon as Ki-Woo steps into the house, he is leaving the chaotic and improvisatory space of working-class Seoul and entering planned, architectural space. Here, light fixtures do not double as drying racks and bathrooms aren’t used for surfing the web. In contrast, every detail of the Park’s house speaks to the logic of its overall design.

This is a living space that has carved out its niche in the social order. It asserts its right to exist.

In ‘Parasite,’ secrets lurk even in spaces that appear meticulously logical in their design. Photo: ⓒ 2019 CJ ENM CORPORATION, BARUNSON E&A

However, the seeming stability of the Park household ultimately proves to be an illusion. The shocking ending of the film illustrates that dark secrets lurk in every house, even ones with open floor plans. It also shows that class tensions can only be tamped down for so long. If inequality persists, and workers continue to be unable to take control of their lives, something is eventually going to crack.

Architects: Showcase your next project through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.