Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Rising 463 feet above downtown Chicago, Tribune Tower is a jaw-dropping relic from a bygone era. Not least because in 2023, nobody has the money for gothic revival skyscrapers, let alone spectacularly ornate buttresses.

1921 was a different story, though, when the Chicago Tribune newspaper ran a competition to mark its 75th anniversary, first prize of $50,000 for whoever could design “the most beautiful and distinctive office building in the world.” The winners John Mead Howells and Raymond Hood did their best to answer that brief, but the most influential aspect about the competition was arguably Finnish architect Eliel Saarinen’s unrealized dream.

Saarinen’s Tower used the gothic blueprint sans superlatives and emphasized verticality. One of the city’s most-respected architects at the time, Louis Sullivan, declared it a vision of the Chicago School’s future. In reality, it was much more. Over the next decade, high rises from New York City (American Radiator Building, Hood’s own Rockefeller Center) to San Francisco (140 New Montgomery, Russ Building) paid homage to a landmark that never was.

As for Tribune Tower, the eponymous publication handed keys over in 2018, ushering in a new era for the address. Three years on, it re-emerged as 162 luxury condominium units with retail thanks to extensive work by the firm Solomon Cordwell Buenz.

Far from an outlier, Chicago’s biggest newspaper wasn’t the only periodical keen that left an indelible architectural mark on its hometown, only to move on as budgets and staff numbers fell. Research for this article relied on those in the direct firing line of such redundancies and cuts — journalists — who were asked for tips on former print media palaces that have since vacated. Case studies came thick and fast.

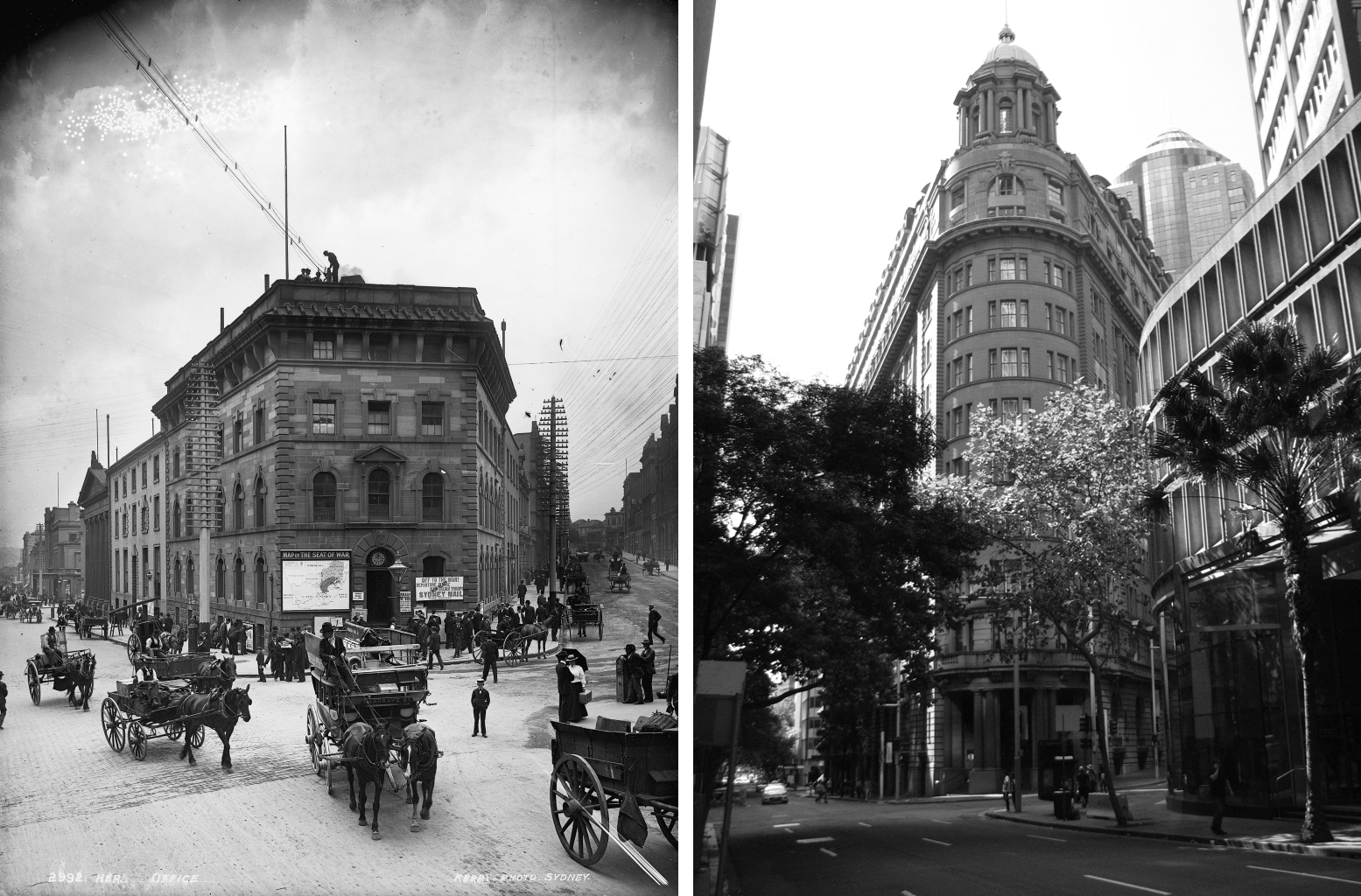

Left: Sydney Morning Herald building built in 1856 on the same site, demolished in the 1920s for the present building via Powerhouse Museum Collection; Right: Wales House designed by Manson & Pickering and built from 1922 to 1929 by Stuart Bros, home to Sydney Morning Herald from 1927 to 1955, Collywolly, Wales House, 64-66 Pitt Street, Sydney 04, CC BY-SA 4.0

Sydney’s John Fairfax Building is said to have produced more newspapers than anywhere on the planet in its heyday, including Sydney Morning Herald and Financial Review. Today, the mid-century modernist edifice falls within the University of Technology. The Herald‘s previous home, sandstone renaissance palazzo gem Wales House, is a hotel.

Likewise, England’s Bournemouth Echo once laid claim to an Art Deco paradise: a beautiful 1930s structure that was testament to the size and power of regional titles. Skip forward eight decades or so, and the tech startups now based within its walls are symbolic of how economies have shifted. One sector superseding the other, in both demand and status.

Built in 1905, The Scotsman’s castle-like complex in Edinburgh served as a home for the newspaper for nearly a century Nevit Dilmen, Edinburgh 1120853 nevit, CC BY-SA 3.0

Similar thoughts spring to mind in Edinburgh. National broadsheet The Scotsman moved to a nondescript purpose built office in 2001, moving out just 13 years later. The building is currently home to Rockstar North, one of the biggest names in video games responsible for, among other things, the Grand Theft Auto franchise. Meanwhile, the paper’s previous HQ, a postcard-worthy Scots Renaissance Edwardian artifact, is home to another hotel. Its connected printing facility is now the City Art Centre.

Elsewhere in Britain, three sites exemplify the difference between second lives of newspaper offices and those of their printing press engine rooms. The Telegraph Building in Belfast’s namesake newspaper and printers have given way to a high spec destination for events. And both a 6,000 capacity music venue in London, and sprawling entertainment complex in Manchester, now carry the name Printworks due to their original functions.

London’s Printworks music venue by Broadwick Live

Around the corner from the latter, the Grade-II listed streamline moderne Daily Express Building, one of Manchester’s interwar trophies, is thankfully once again occupied after dereliction. Co-working specialist Huckletree is spread across three floors, offering opportunities for startups, creatives and freelancers. And plenty to think about in terms of the way we conduct business, and how much this has changed since the millennium.

Of course, the fall in the revenue and status of newspapers is an extreme model. In the first two months of this year, many US institutions, including The Washington Post, again made brutal cuts. The UK’s biggest regional publisher, Reach, is currently in its second round of redundancies for 2023, and we’re not even through March.

Stephen Richards, Express Building Manchester, CC BY-SA 2.0

Industry bible Press Gazette, meanwhile, reported around 1,000 job losses across all English speaking titles in January alone. A long-standing trend, according to Pew Research Center, by the onset of the pandemic in 2020 American newspapers were running with 57% less employment compared with 2008.

The media is not alone in downsizing, either. Tech firms have actioned over 100,000 layoffs since New Year. Meanwhile, post-lockdown remote and hybrid working practices have not only catastrophically impacted hospitality in urban centers, but lowered commercial real estate values and cast some doubt over the viability of large HQs. As the artificial intelligence and machine learning arms races gather pace, that quandary is going nowhere.

So it’s no surprise the re-appropriation of office and commercial buildings is an increasingly prominent aspect of architecture and planning in the 21st Century. The scale of operations in the world we had appears to far exceed what’s needed for the world now under construction. How we decide to move forward today will dictate the makeup, function and footfall of towns and cities for decades. The real question is, then, how do we fill these vacuous holes in response to the genuine needs of place and people?

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.