Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.

Much ink has been spilled over the death of the shopping mall. Pandemic restrictions exacerbated the looming threat already posed by the rise of online shopping. However, while the 20th-century version of the shopping mall, with its food courts, fountains and a heavy-hitting department store anchor, is increasingly seen as a relic of a bygone era, the shopping center typology is still alive and well — it has simply taken on new forms.

Malls have long been tied to their birthplace; in the past decades, shopping centers have been to the United States what piazzas are to Italian cities. Popular culture has cemented their association with American lifestyles. While other countries have long looked to the shopping mall as a manifestation of capitalism, around the world, shopping center construction is on the rise, and its various global manifestations are translating the language of the mall typology. Indeed architects, developers, city planners and store owners are just a few of the many stakeholders collaborating to rethink the idea of the shopping center, and its value to cities in the 21st century.

Yonge Sheppard Centre by BDP Quadrangle, Toronto, Canada

Popular Choice, 2021 A+Awards, Shopping Center

America’s first shopping mall was designed in 1956 by Victor Gruen. The Austrian-born architect set out with an admirable goal of making American cities more like their pedestrian-friendly European counterparts. America was very automobile-centric, and he sought to use architecture to coax people from their cars and interact with one another. Nowhere was this more true than in the suburbs. For Gruen, malls were about more than just shopping: they were also meant to be community-building green spaces. In his original conception, the malls would be connected to commercial and residential buildings and public areas. (Later in life, Gruen recognized that he had inadvertently fostered the opposite culture, and disowned his architectural child in 1978, famously stating that he “I refuse to pay alimony for those bastard developments.”).

Before Gruen, shopping spaces were always oriented towards the street. His first mall in Edina, Minnesota, was built two years after he experimented with an outdoor shopping center design. The revolutionary aspect of this indoor instantiation was the introspective nature of the architecture: the building was almost turned inside-out so that all activity was done inside, and blank walls (rather than glazed storefronts for window display) faced the parking lot. The nucleus of the building was an open court with fountains, plants, and art; this central space, which was flooded with natural light from a skylight, sculpted tree, balconies and hanging plants, was then surrounded by corridors lined with storefronts. His firm would oversee the design of over fifty more malls in the following decades, as the mall climbed a precipitous ascent in popularity, only to crash after the turn of the 21st century.

Malls have long been seen as maze-like places that are designed to make people lose track of time and space; and, while this was not Gruen’s initial intention, the physical design of malls themselves (and, by extension, architects) are not widely held as suspects in its death. Indeed, they are increasingly seen as potential rehabilitators, capable of bringing new life to these languishing structures, as is seen in the reinvention of The Yonge Sheppard Centre in Toronto. In this example, BDP Quadrangle activated retail streetscape and introduced naturally-lit atriums in their reimagining of this 1970s commercial space. Theirs was an urban-oriented intervention that sought to revitalize the surrounding urban areas; it is also a success story for the continued relevance of architectural complexes that house a variety of stores.

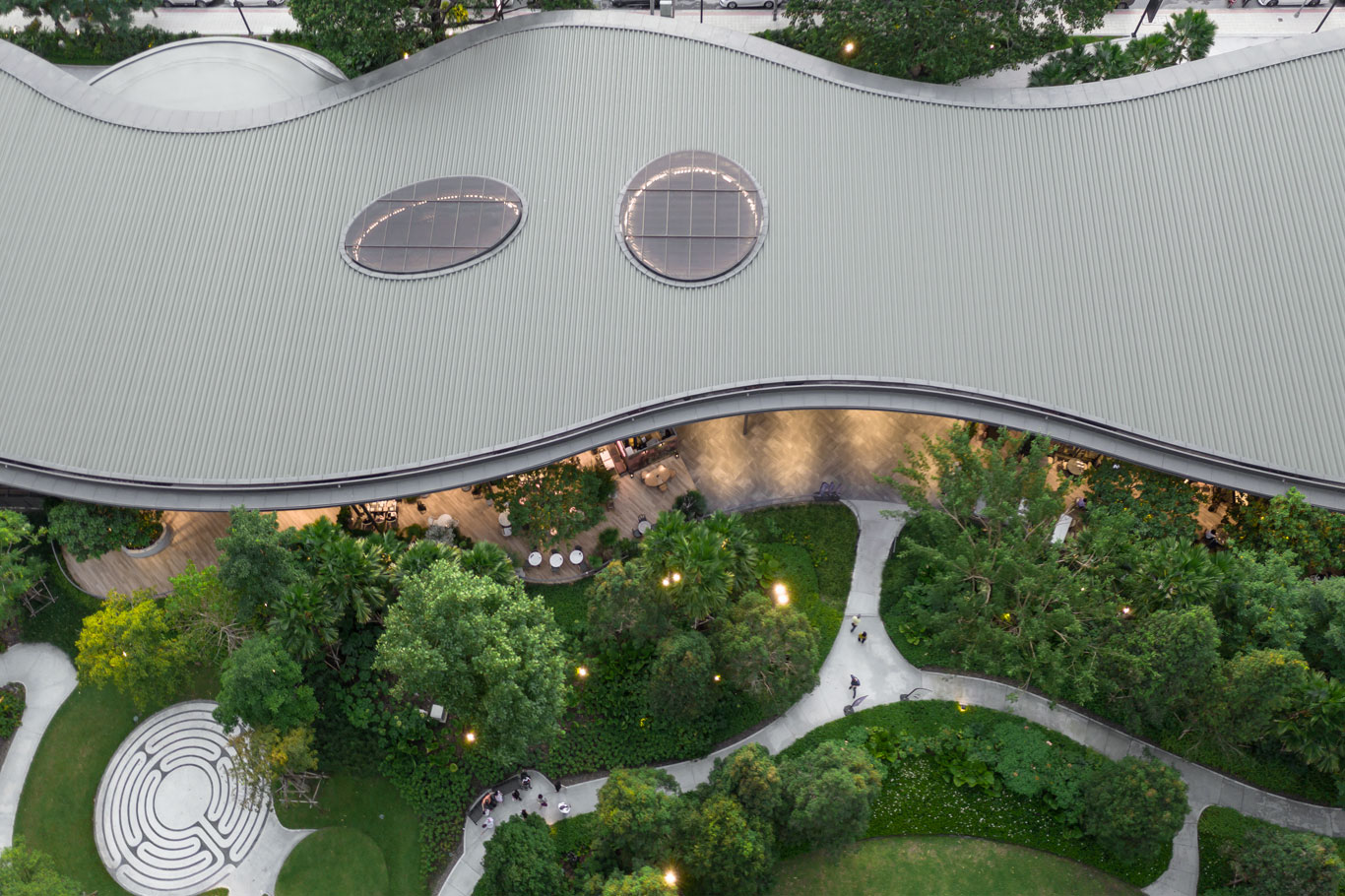

VELAA (THE SINDHORN VILLAGE) by Architects 49 Limited, Bangkok, Thailand | Photos by W Workspace Company Limited (15)

Popular Choice, 2021 A+Awards, Retail

Yet, while architects can adapt the physical spaces of existing malls, there are larger forces putting pressure on the typology. Even just the opening of new competing shopping centers in proximity to older buildings often puts those older malls out of business. Moreover, while e-commerce often takes the fall for the fate of the shopping mall, culpability extends beyond online shopping. Economic downturn and changing commercial habits are contributing factors, but the death of the department store (by the hollowing out of the American middle class) is largely to blame — Macys, Sears, and more used to be the anchors of many shopping centers.

In response to these changing consumer habits, malls are now being reimagined as urban-oriented, mixed-use spaces. Prior to the internet, visits to the mall involved browsing. Nowadays, shoppers arrive with a specific mission; they often know what they want before arriving and can beeline to the stores that meet their needs. In response, designers and developers are trying to draw visitors by creating thriving communities that resemble town centers (not unlike Gruen’s original vision for shopping malls). Instead of focusing on the box store as an anchor, architecture and design are taking center stage. So, how can designers tasked with engaging the public respond to such pressures?

The Sindhorn Village in Central Bangkok exemplifies many of these trends. The luxurious, mixed-use development is a new landmark that aims to inspire modern, sustainable urban developments. The master plan features a generous green space with a low-density ratio; it contains a condominium, serviced apartments, a hotel and restaurant, an art museum. Finally, a single-story semi-outdoor retail mall merges with this green space and includes cafes, restaurants, shops, services and a below-ground supermarket. In addition, areas dedicated to community use, or “green courts,” are interspersed throughout this complex.

The meandering open plan allows for natural ventilation, eliminating the need for air conditioning. At the same time, branches of treelike columns support the perforated canopy roof over the shopping areas and pedestrian walkways to accentuate the experience of strolling in a park. Rays of light seeping through the roof canopy of the five main courts shimmer and create shadows below like the pattern of leaves, allowing natural light to the interiors. Lighting design, both warm and welcoming, illuminates the night through the perforations like fireflies in an enchanted forest.

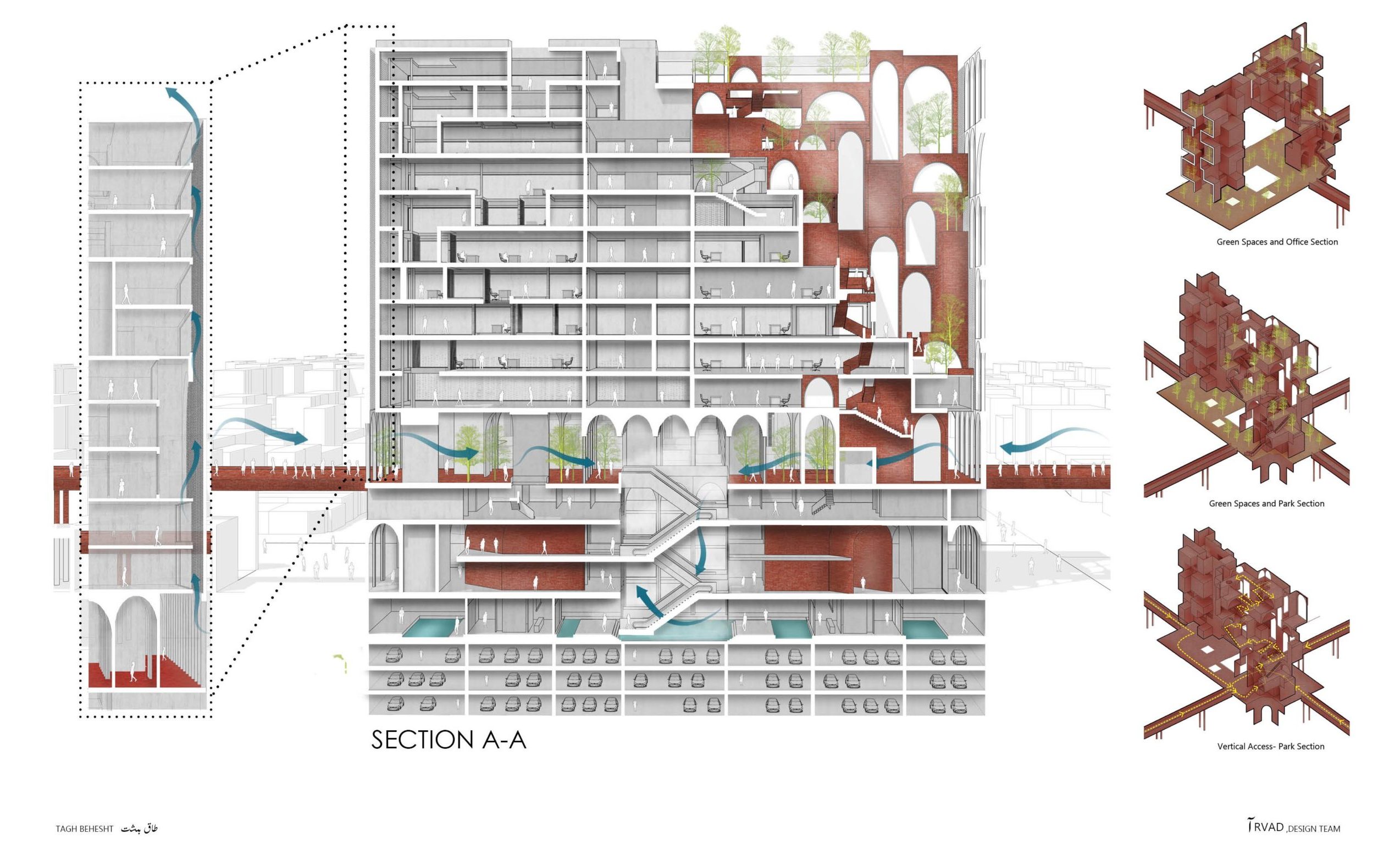

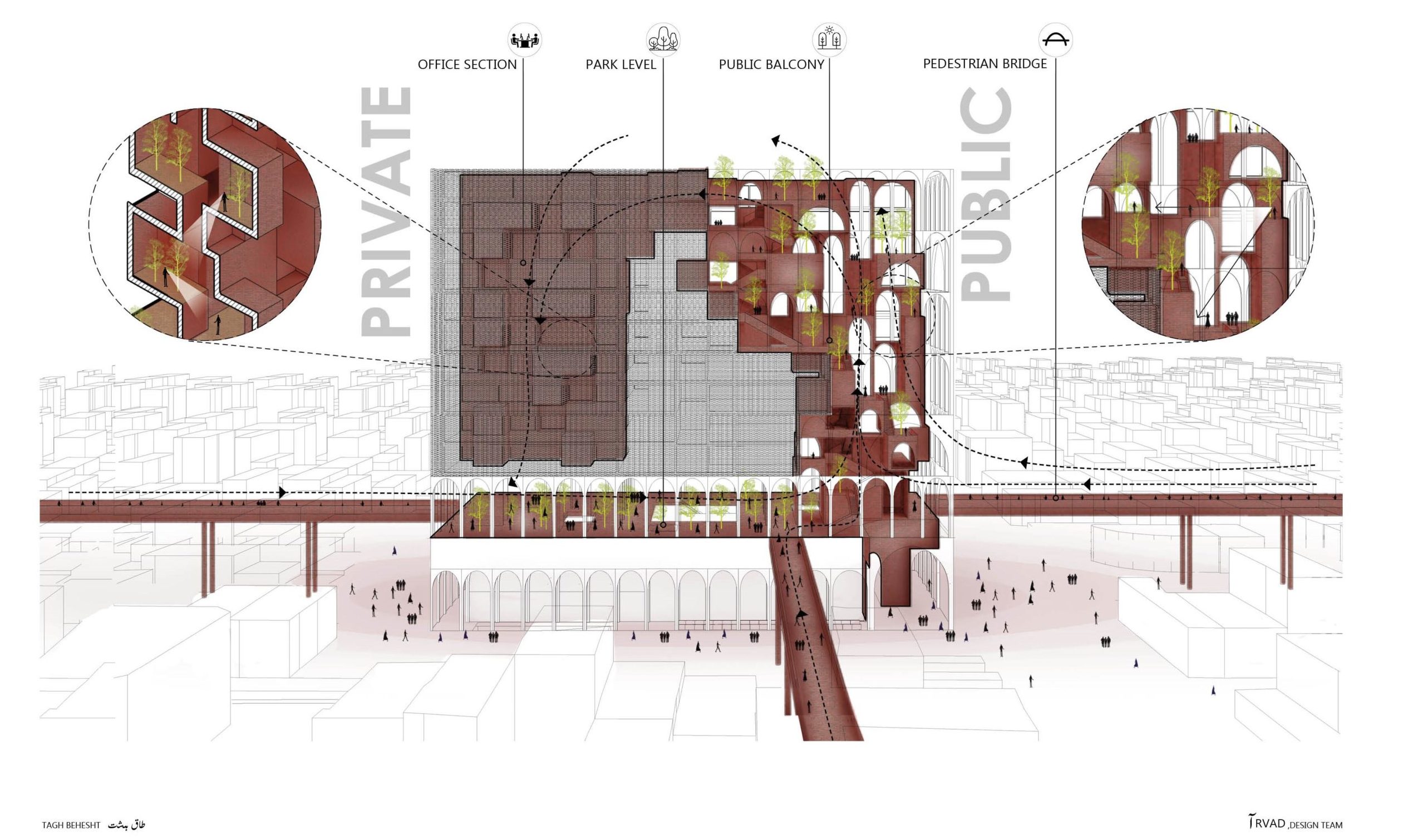

Tagh Behesht by Rvad Studio, Mashhad, Iran

Jury Winner, 2021 A+Awards, Unbuilt Commercial

Like the forum in ancient Greece, or the market square of medieval Europe, societies have long paired public space with commerce; in the decades that followed the birth of the shopping mall, Gruen’s invention became a stand-in for the main street in many North American suburbs. Yet, much to his chagrin, they remained bound to car culture and, more often than not, were detached from urban life. Part of the twenty-first-century rebranding of the shopping center returns to the roots of the typology as a civic destination, and architects are reaching further back in history to precedents set long before the 1950s. This approach often results in designs that appeal to all ages and incorporating indoor and outdoor spaces so that retail spaces are integrated with their larger urban context. Such an approach is exemplified by Rvad Studio, who recently returned to the traditional Iranian bazaar to design a shopping center integrated with the city and culture.

Tagh Behesht investigates how shopping centers can become social and economic vital sites that also introduce much-needed green space into dense city centers. The inspirational inquiry earned the remarkable Tehran-based studio — founded in 2020 — international accolades when the resulting project took home the Jury Winner prize in the 9th Annual A+Awards. Taking the architectural history of bazaars in Iran and the city of Mash-had as a jumping point, one of the main ideas in the design is the use of pedestrian bridges to create safe and enjoyable walkways away from city traffic. A flat middle garden, much like a city junction, is the intersection between all suspended pedestrian bridges and acts as the project’s central connection hub. One of the more exciting design components is the suspended courtyards in between the office areas, which provide green spaces for all floors and business units and sufficient and direct light.

As the developers and entrepreneurs rethink the central tenets of the industry — from tenants to site — architects are playing increasingly important roles in drawing visitors (in the past, these customers were assumed, and the stores simply pushed their products). As architects continue to rethink shopping centers, transforming them into mixed-use places to better engage visitors, commercial transactions and product sales are increasingly seen as byproducts of the design (rather than its raison d’etre). As parking lots fall to the wayside in favor of proximity to foot traffic, bike paths and public transit, the buildings are becoming essential urban revitalization tools.

Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.