Ema is a trained architect, writer and photographer who works as a Junior Architect at REX in NYC. Inspired by her global experiences, she shares captivating insights into the world’s most extraordinary cities and buildings and provides travel tips on her blog, The Travel Album.

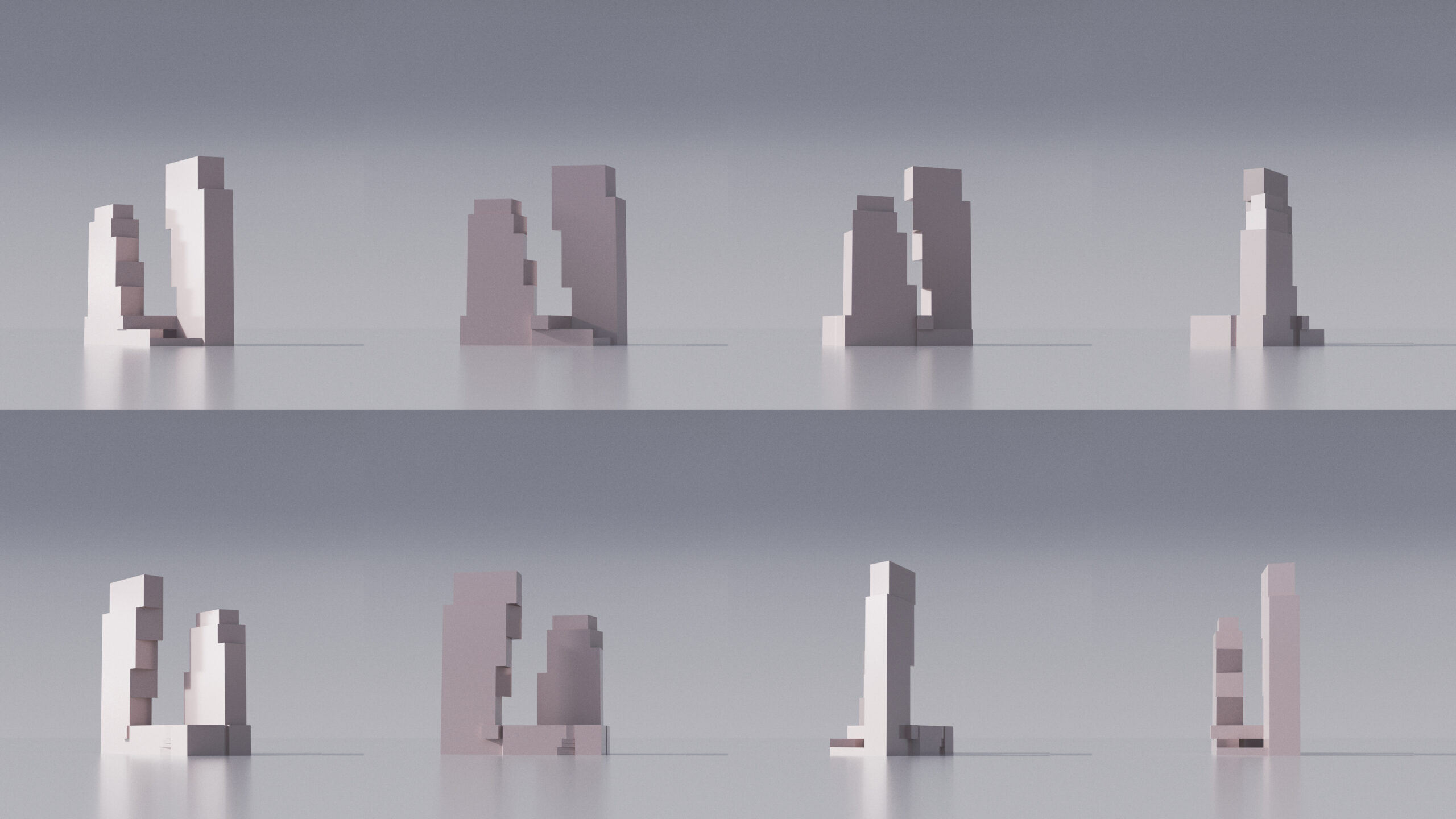

In the world of architecture, the iterative process is often hailed as a crucial phase of design development. This method, characterized by repeated cycles of trial and error, is intended to refine and perfect architectural concepts. However, there is a growing concern within the industry that iteration can sometimes become an end in itself rather than a means to an end. Architects might find themselves exhausting every possible option before choosing the final design, a practice that can have significant implications for employees and the overall culture of an office.

Is it truly necessary to exhaust every possible person, shape, angle, direction, size and color just to demonstrate that adequate effort has been put into a project?

The Iterative Process: A Double-Edged Sword?

Iteration is undeniably a valuable tool in the architect’s toolkit. By exploring multiple design options, architects can uncover innovative solutions and push the boundaries of conventional design. This process allows for the refinement of ideas, leading to more robust and thoughtful outcomes. However, when the focus shifts to iterating for the sake of iteration, it can lead to a cycle of endless revisions that may not necessarily contribute to the overall quality or integrity of the final design.

In many architectural firms, the pressure to explore every conceivable option before settling on a design can create a taxing work environment. Employees may feel overwhelmed by the relentless demand for new iterations, especially when many ideas are overlooked and not thoroughly discussed. This constant cycle can lead to frustration and a sense of futility in the creative process. The iterative process, when not managed effectively, can create a culture of overwork and stress, where the quantity of designs takes precedence over the quality.

The Culture of Iteration

The culture of iteration in an architectural office can significantly influence the work atmosphere and the morale of the team. While a rigorous iterative process can foster creativity and innovation, it can also create a sense of endless pursuit without clear direction. Employees might find themselves questioning the purpose of their efforts, particularly if they feel that their iterations are being produced merely to satisfy the demands of the process rather than to achieve a meaningful design goal.

To foster a healthy and productive work culture, I believe that it is essential for firms to strike a balance between iteration and intentionality. Architects must be encouraged to iterate with purpose, ensuring that each version of a design brings them closer to a coherent and well-thought-out final product. This approach not only enhances the quality of the design but also instills a sense of purpose and direction among employees, contributing to a more positive and motivating work environment.

Intentional Design: The Power of Purpose

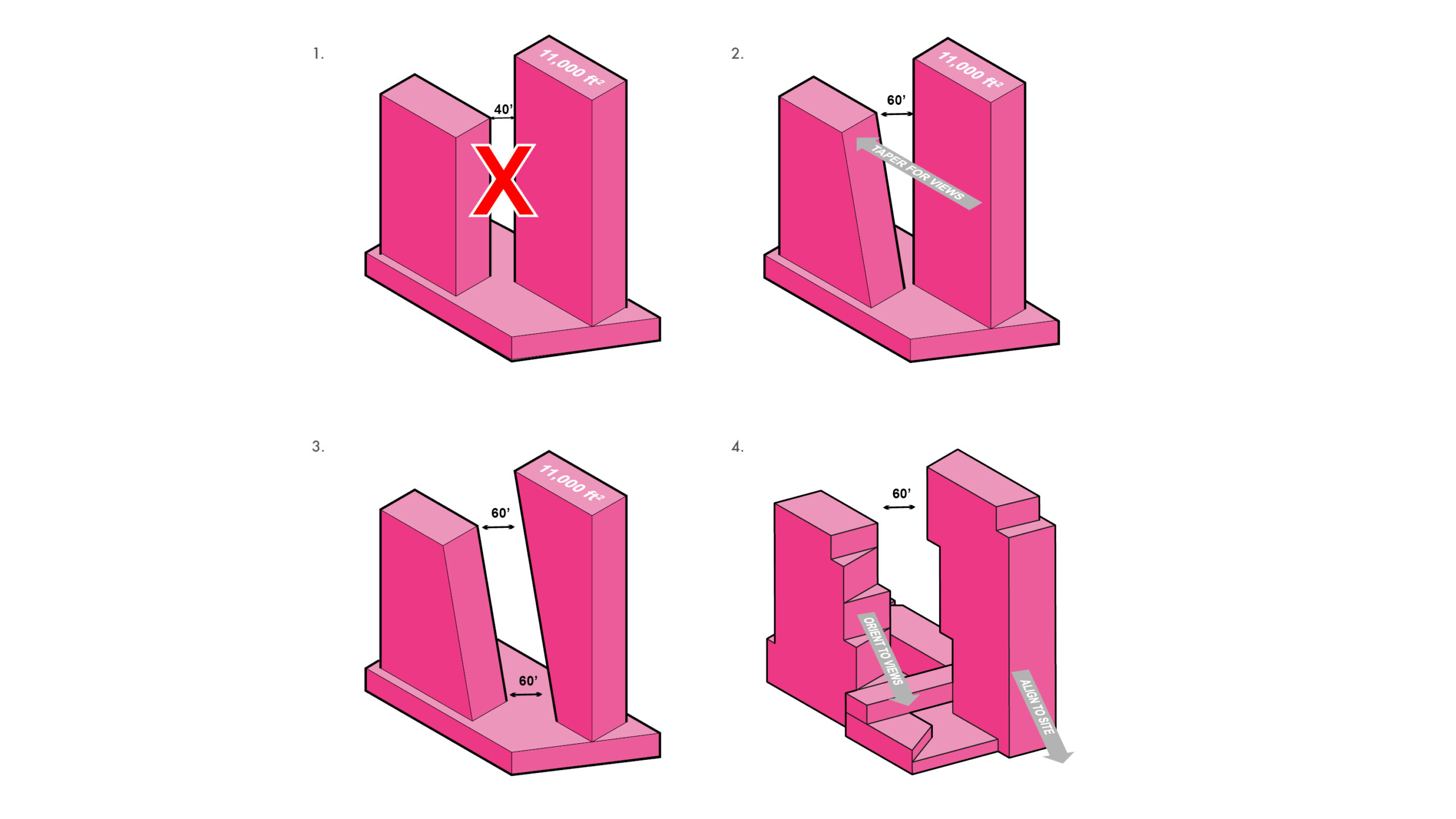

Greenpoint Landing by OMA, New York City, New York

Intentional design is the antidote to the pitfalls of excessive iteration. At its core, intentional design is about making deliberate choices that are grounded in a clear understanding of the project’s goals, context, and narrative. It involves creating buildings that are not just visually appealing but also meaningful and functional. Each design decision is informed by a story, a concept, or a purpose, ensuring that the final product is more than just an arbitrary collection of shapes and forms.

I’ve often found myself in a predicament where I’m instructed to design a form for a program, client, or purpose that remains largely undefined. Once I craft a shape, based on what seems most suitable for the site conditions, I must then force the program into this form – and that’s where the issues start. We become obsessed with the form itself, rather than considering if it truly serves the project’s best interests.

Architects who embrace intentional design are more likely to produce buildings that resonate with their users and the broader community. From my experience, I have found that most architects claim their designs have meaning and purpose, but is that really always the case? Buildings should tell a story and offer a unique experience, making them stand out in a crowded architectural landscape. By focusing on the purpose and meaning behind each design element, architects can create spaces that are not only beautiful but also deeply connected to their context and function. Many designers claim to prioritize both form and function, but in my experience, form has often taken precedence over functionality, which is not a perspective I fundamentally agree with.

The Role of Storytelling in Design

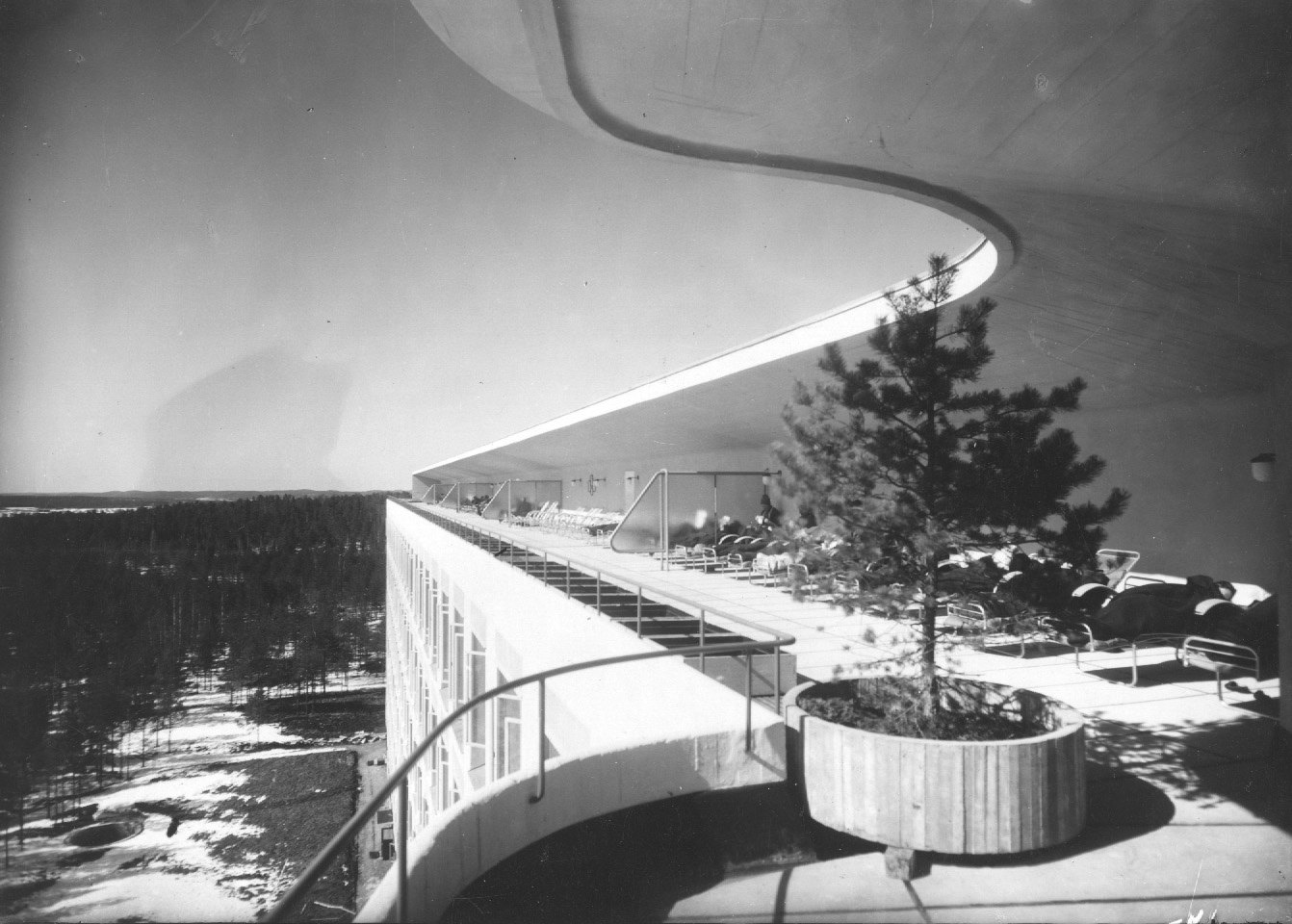

A key component of intentional design is storytelling. The most compelling architectural designs often evolve from a narrative that guides the development of the project. This narrative can be rooted in the history of the site, the cultural context, or the needs and aspirations of the users. By weaving a story into the design process, architects can ensure that their buildings are grounded in a meaningful context, making them more relatable and engaging.

For example, a building designed to serve as a community center might draw inspiration from the local history and culture, incorporating elements that reflect the community’s identity and heritage. This approach not only enhances the building’s aesthetic appeal but also fosters a sense of ownership and pride among the users. The design becomes a reflection of the community’s values and aspirations, creating a deeper connection between the building and its users.

Rethinking the Iterative Process

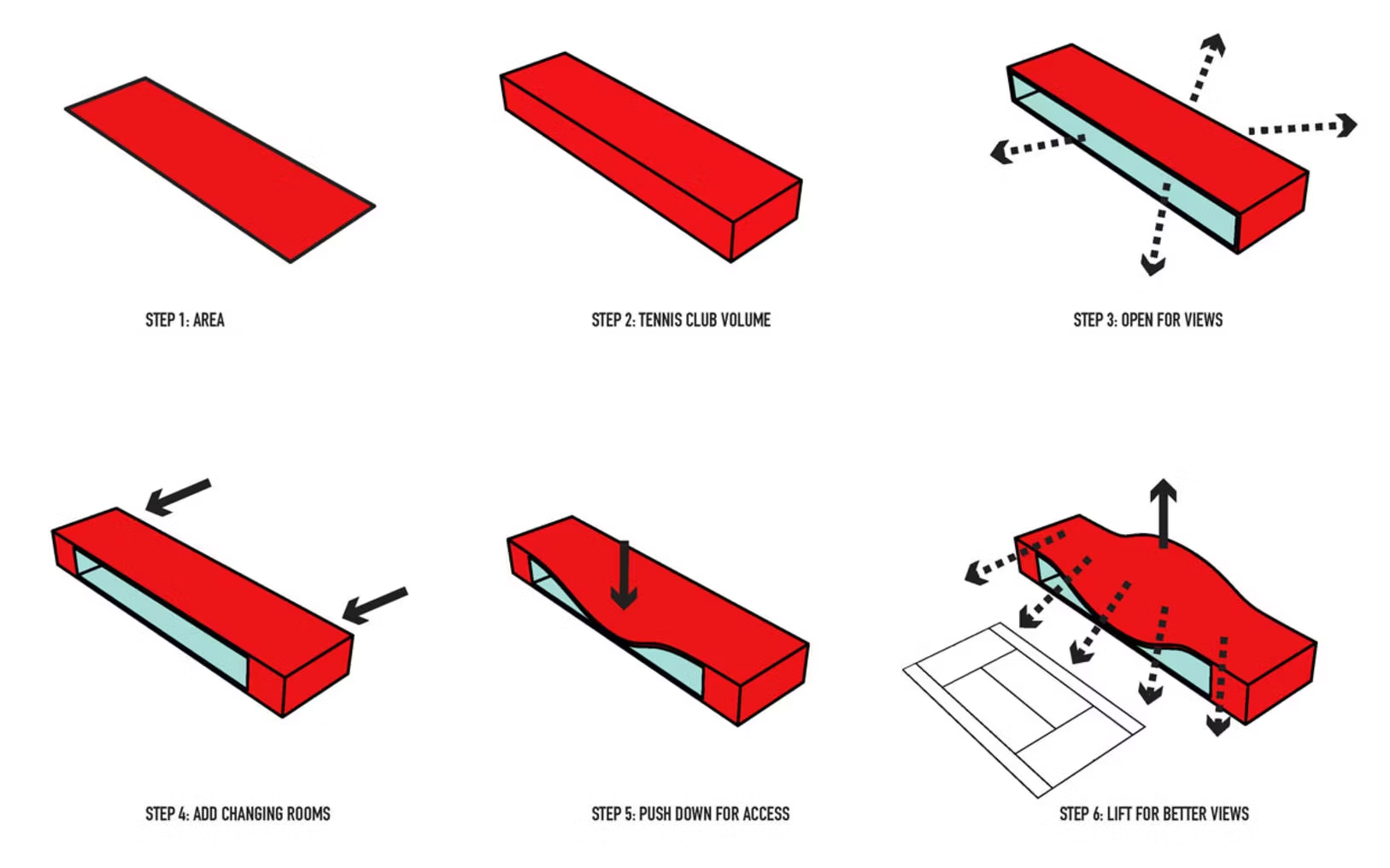

The Couch by MVRDV, IJburg, Netherlands | Beginning with a simple cuboid, the volume is manipulated to provide views for spectators across the court and the wider region while maintaining space within the structure to house changing rooms.

The iterative process is a powerful tool in architectural design, but it should be used wisely. When iteration becomes an end in itself, it can lead to a cycle of endless revisions that detract from the quality and purpose of the final design. To avoid this pitfall, architects and designers should embrace intentional design, ensuring that each iteration is guided by a clear purpose and meaning. This doesn’t mean you can’t be playful and experiment with different designs and strategies. However, when this phase extends too long and people produce dozens of designs that ultimately aren’t considered or discussed in design meetings, it can be quite disheartening.

By focusing on intentionality and storytelling, architects can create buildings that are not only visually stunning but also deeply meaningful and functional. This approach fosters a more positive and motivating work culture, where employees are inspired by the purpose behind their efforts. Ultimately, intentional design leads to better buildings that enrich the lives of their users and contribute to the vitality of their communities.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Top image: Greenpoint Landing by OMA, New York City, New York