Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

”Don’t bother visiting Brasilia if you’ve already formed an opinion and have preconceived ideas. Stay where you are. Let them say what they want; Brasilia is a miracle.”

— Lúcio Costa

We live in Jane Jacobs’ world. The thesis of her landmark 1961 book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, is more or less assumed by most people with an interest in urbanism. For those who need a refresher, Jacobs argued powerfully that centralized city planning often backfires, producing urban spaces that are less workable than neighborhoods that develop organically. As she put it, “Cities have the capability of providing something for everybody, only because, and only when, they are created by everybody.” Against the authoritarian imagination of her nemesis, Robert Moses, Jacobs proposed a vision that was purportedly more democratic. (Emphasis on purportedly. We will get back to this…)

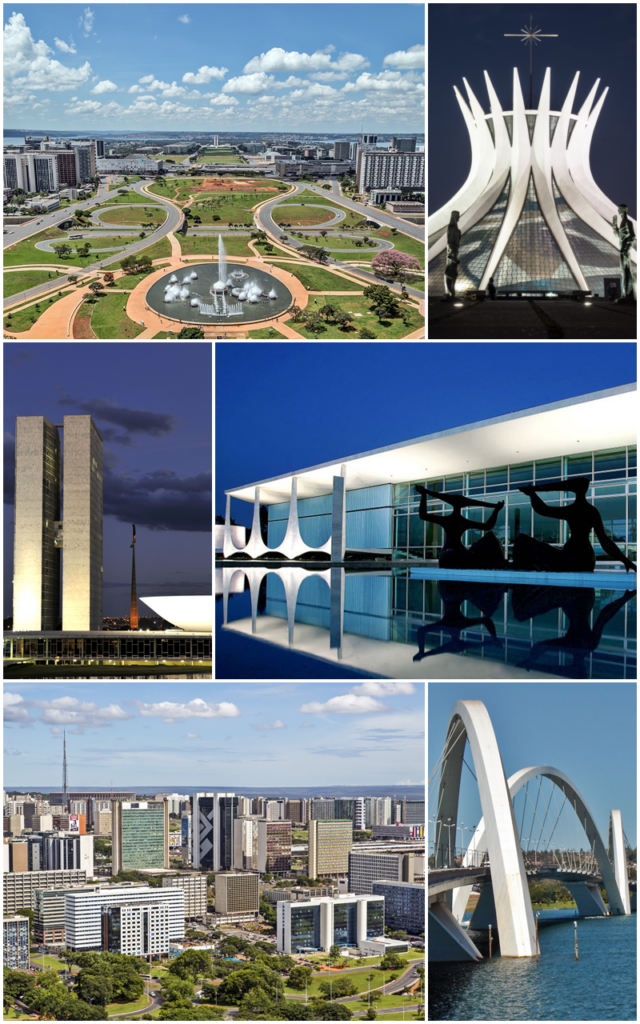

Collage of Brasília. From the top, clockwise: Monumental Axis seen from the TV Tower; Metropolitan Cathedral at night; facade of the Alvorada Palace; Juscelino Kubitschek bridge in Paranoá Lake; buildings of the South Banking Sector and the National Congress building with the national mast in the Three Powers Plaza at the background. Chronus, Brasília Collage, CC BY-SA 3.0

Nowhere are Jacobs’ ideas more applicable than in the case of Brasília, the Brazilian capital that was centrally planned by Lúcio Costa, Oscar Niemeyer, Joaquim Cardozo and Roberto Burle Marx, and built from scratch between 1956 and 1961. Originally considered a triumph of modernist design and urban planning, the city is often pointed to today as a failure, even a cautionary tale against the modernist dream of building utopia. And indeed, the city really does have problems that align with Jacobs’ critiques of modernist urban planning.

For one thing, the infrastructure of Brasília is far too dependent on cars. For another, the separation of residential and commercial zones give it a sleepier, less lively feel than Rio or São Paulo. As Brazilians say, the city “lacks street corners.” Finally — and most devastatingly for the architects, who were aligned with modernism’s egalitarian ethos — the city is very segregated by class, with working class citizens living mostly in the suburban satellite cities that sprawl outward for miles. The original scheme of mixed income communal superblocks didn’t work out as intended.

So Brasilia didn’t “work,” or at the very least it did not manifest utopia. It shares the same problems with the rest of Brazilian society — class stratification and pollution to name two — plus a few problems of its own, mostly owing to the fact that it is not friendly to pedestrians. From this, critics have concluded that planned cities don’t work. Robert Hughes, in his 1980 book The Shock of the New, put the consensus most memorably. “Nothing dates faster than people’s fantasies about the future,” he wrote. “This is what you get when… you design for political aspirations rather than real human needs. You get miles of jerry-built platonic nowhere infested with Volkswagens. This, one may fervently hope, is the last experiment of its kind. The utopian buck stops here.”

A more prosaic view of Brasília. A roundabout downtown. Mariordo (Mario Roberto Duran Ortiz), BSB 08 2012 rondabout 4384, CC BY-SA 3.0

On first blush, Hughes’s view seems rooted in common sense. Conservatives like Tom Wolfe loved this book. But still, one has to ask: is Brasília really less workable than, say, Los Angeles? The latter is also car-dependent but has far more congestion. And is the class segregation in Brasília really worse than in Rio? Are isolated housing blocks really worse than favelas? And if Brasília failed to achieve its aims, does this mean it wasn’t even worth attempting? Do Brasília’s shortcomings mean, as Hughes claimed, that city planners should not allow themselves to dream big?

My answers to these questions are no, no, no, no, and no.

The problems with Brasília are easy to identify. But there is also a problem with Jacobs and her perspective, which is that it avoids the question of capitalism. Greenwich Village did not emerge organically; the corner shops and tree-lined brownstone streets that people love so much were built to meet the demands of an older economic and political moment. I actually agree with Jacobs that zoning laws should be changed to allow for more mixed use, dense urban development of the sort epitomized by Greenwich Village, but I reject the idea that this is not itself a utopian vision. The Jacobs acolytes, observing what went wrong with Brasília, should fight to scale their view of a workable city, thinking through the big questions of what kind of housing and transportation infrastructure could really work for cities that are growing and changing rapidly.

Housing blocks in Brasilia under construction, 1959. Brazilian National Archives, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Here’s why it matters, especially for readers in the US, where I am based: right now, American cities do not work, and it is not the fault of Robert Moses. The biggest problem that I can see is a lack of housing supply, which is driving prices through the roof. To solve this, a massive amount of construction is needed. Central planning is also needed in order to ensure that these new developments can be integrated into the economic, social, and cultural life of cities. It is not enough to expect these problems to somehow work themselves out on their own. If we don’t shape our cities, capital will.

Modernism’s vision of rationally planned cities that aspire to social equality is analogous to another 20th century dream that many are eager to declare a failure: social democracy. The New Deal policies that built the American middle class in the postwar era — imperfectly, it must be added — have been systematically eroded since the 1980s. Reagan and his ilk encouraged voters to place their trust in the market, arguing that it was a mechanism for societies to work through problems without any top-down government diktats. This revolution didn’t work, as has been well-documented, producing a host of social, economic and environmental catastrophes in its wake.

Housing blocks in Brasilia are often elevated on pilotis and surrounded by lush green space, according to the modernist plan. victoria.camara, Vista aérea da Asa Sul em direção ao Centro, CC BY 3.0

The time has come, once again, to think big. With rising populations in the US, Canada and elsewhere, urban spaces must be transformed and done so in ways that meet the needs of the working classes. Doing so will take imagination and courage — the very qualities exhibited by Lúcio Costa and his collaborators in the construction of Brasília.

In the beautiful, gleaming monuments of Oscar Niemeyer as well as in the lush parks of Roberto Burle Marx, one can still feel a flash of optimism. This is a spirit that has dimmed in our century. Recapturing it, and doing so by putting forward a bold and positive vision of the future, is the historic task not only of the political left, but of architecture as a discipline.

Speaking in these terms might sound lofty. It’s not the register I am most comfortable with, believe me. But in order to build the future, we need to be willing to step outside our comfort zone.

Cover image: A view of Eixo Monumental as seen from the east, looking towards Esplanada dos Ministérios and the National Congress of Brazil, both visible in the background. Arturdiasr, Planalto Central (cropped), CC BY-SA 4.0

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.