The architectural visualization field is rapidly growing, transforming how architects, designers and clients experience projects — both built and unbuilt. As architecture continues evolving in complexity, so does the importance of creating the right visuals. Architectural visualization is a growing field and an alluring career path for those passionate about design and storytelling.

Such is the case with Francisco Tirado. Currently working as a Photography Lead at Cobe, Francisco has spent over a decade perfecting his craft, capturing the essence of architecture through stunning imagery. With experience spanning roles from design architect to freelance visual artist, he’s captured over 350 projects and has been featured in 60+ media outlets worldwide. Notably, he was voted Architectural Photographer of the Year at Architizer’s 2023 Vision Awards.

This October, Francisco will be a keynote speaker at the World Visualization Festival (WVF) in Warsaw. The WVF invites architectural visualization professionals to engage in workshops, presentations and networking sessions. With a focus on entrepreneurship, new industry standards and technology integration, the festival provides a platform for professionals to learn from leaders in the field and connect with peers from renowned firms like Henning Larsen, MVRDV and DBOX.

We sat down with Francisco to discuss his journey from architecture to photography, his role at Cobe and the insights he plans to share at the WVF this October.

Kalina Prelikj: You’re a trained architect and have been working in the industry for some time. What led you to shift your focus from designing buildings to capturing them through photography and visualization?

Kalina Prelikj: You’re a trained architect and have been working in the industry for some time. What led you to shift your focus from designing buildings to capturing them through photography and visualization?

Francisco Tirado: In 2013 I graduated as a licensed architect and like many of us “sons of the financial crisis,” I had to find my way in the industry to make a living. I worked as a traditional architect for two years before graduating, combining it with working as an English teacher, computer repair specialist, operator in a call center and construction builder. Basically, I took any available job that I could do. Those from countries hit hardest by the crises will completely understand this, as millions of people went through the same. The need to reinvent yourself to survive was essential at the time.

The thing is, during those years, I didn’t even realize I could make a living creating images. I did, of course, do all the visuals for my own projects and helped other colleagues and everyone loved it, but at the time, I didn’t think much of it. Don’t get me wrong — when I look back at those images now, I think, “Oh boy, this looks horrible,” but to be honest, I feel that way almost every time I look at my old work.

“Sun Hit” by Francisco Tirado, Winner of Architizer’s 2022 One Rendering Challenge

While searching for jobs as an architect, someone saw my portfolio and visuals and offered me a role as an external image supplier instead of a traditional architect, focusing solely on creating images for them. That’s when I discovered that some companies and professionals did this full-time. I remember visiting studio websites, watching tutorials and having a revelation — something I was doing naturally and for fun could actually pay my bills!

I had no idea about freelancing, costs or how much to charge. By the way, this is another reason to attend the WVF: if you’re a freelancer or want to become one, you can learn how to do so properly from professionals. I can’t stress enough how important this is early in your career. But then I did my first visual project for an architecture studio. It was a competition and they won it. This created a snowball effect: more and more projects kept coming and I haven’t stopped doing architectural imagery ever since.

What happened after that day has been a crazy journey that took me around four countries, collaborating and doing all sorts of visual work for more than 300 projects. Finding myself on a plane doing aerial professional photography in Denmark was something I never saw coming when I was an architecture student. And to think that it all started in a little room, in a village in the south of Spain, surrounded by orange trees and very hot summers, while working on a laptop with severe overheating problems.

The Redmolen / Tip of Nordø by Cobe + Vilhelm Lauritzen Architects, Nordhavnen, Copenhagen, Denmark | Photo by Francisco Tirado

KP: You mentioned the importance of learning the ropes of freelancing early in your career and how the WVF is a great place to learn more about that. As a featured speaker this year, could you tell us more about what you’ll be covering in your talk and how it could benefit attendees?

FT: For architects, visualization artists and photographers (or actually, for anyone who can frame and sell their work), going freelance either full-time or part-time is likely going to happen at one point in their career.

When you know how to build something that can be sold easily, at some point you’ll get the question: “Hey, I need this. How much would you charge me for it?” You need to be ready for that question because it will come. How you answer it can make all the difference. It could lead to more work and more commissions or it could lead to failure, burnout and earning very little.

Nowadays, there is a lot of information out there, but events like the WVF will help you find people who have already done it and already failed before you, meaning that you can learn from their mistakes. Don’t get me wrong, you will make mistakes, a lot of them, but you will gain more knowledge on how to deal with them. For newcomers to the business or for those who never freelanced before, it is priceless to listen to the experience of professionals who’ve already done it.

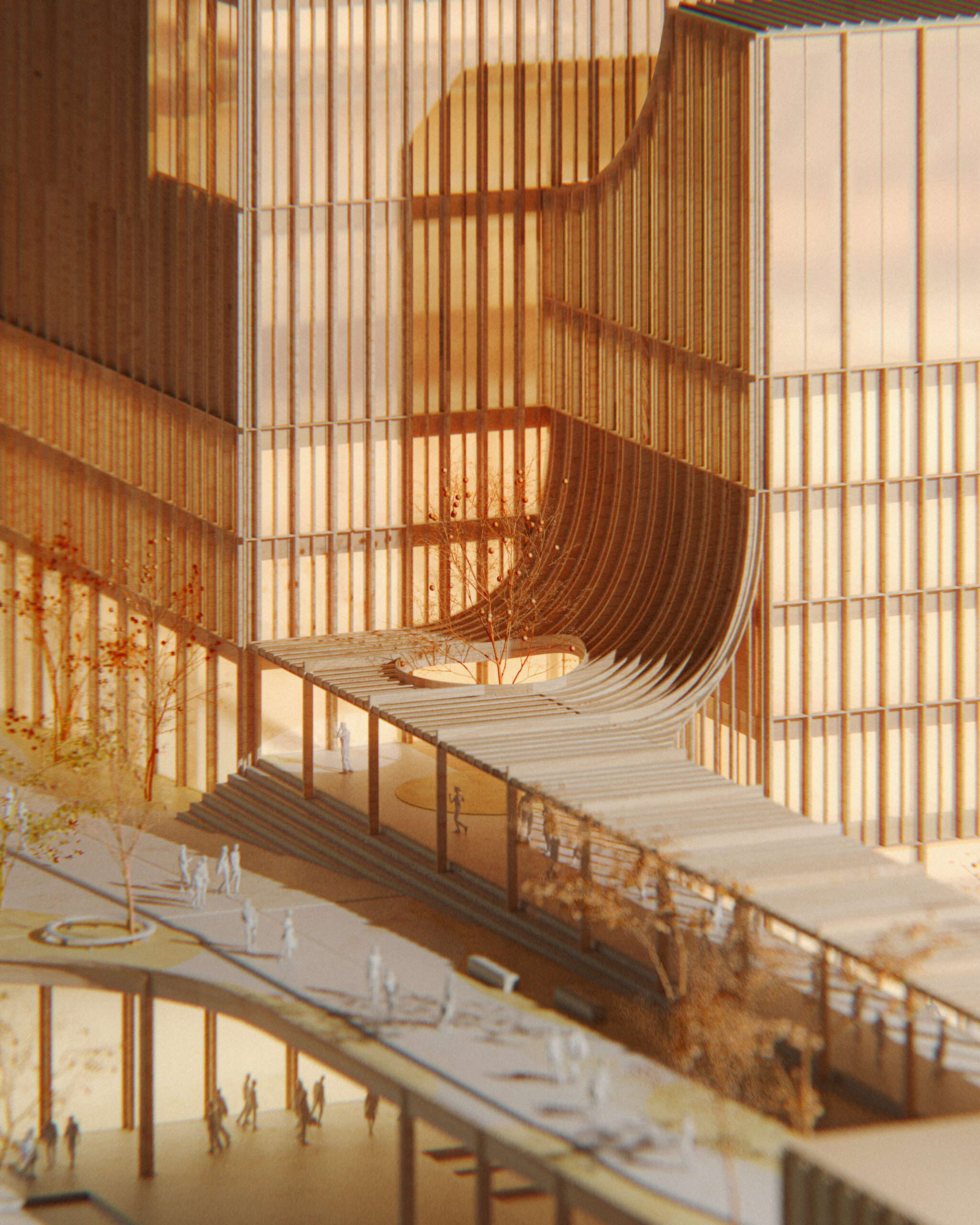

A model of Espoo House by Cobe, Espoo, Finland | Photo by Francisco Tirado

I was a freelancer for around three years before joining Cobe. Maybe I was lucky since I had good friends and connections. I made so many mistakes that I can’t even remember, but in the end, I survived.

So for my WVF talk, I’m going to share how I did it and why I made certain choices, the mistakes I made and the lessons I had to learn along the way, from a humble and honest perspective. I will not be talking about the artistic side, 3D skills or tricks for creating more realistic images, but rather the practical aspects like making annual calculations, budgeting and developing the right mindset.

Being on my most honest humble side, I am going to talk about how I did it and why I did it, what mistakes I made and what I had to learn at the time. Things that are not art, not the 3D qualities, not tricks to do more realistic images, but other things such as making annual calculations, budgeting and mindset.

And this brings me to something else I want to mention.

I believe it’s important to try working on your own, even if just for a little while. Don’t take it too seriously or see it as a final destination, but give it a shot. Doing so will help you understand the value of your work, how to deal with clients, what the market looks like, how to manage your time and how to build your resources. This experience will prepare you incredibly well for the industry because even if you decide to join a company later, you’ll be in a much stronger position than if you were just entering with artistic skills alone.

That’s what I did and that’s how and why I joined Cobe later in 2018. So for me, it was a great learning experience that led me to a place I thought I could never reach.

Portable Solar Distiller by Henry Glogau, Chile | Photo by Francisco Tirado

KP: Not many firms have in-house photographers. What does your role as the in-house Photography Lead at Cobe involve and do you still engage in any design work? What are the advantages of working so closely with the design team?

FT: Cobe has something you can feel the moment you walk into the office — an atmosphere that’s hard to put into words. I’m sure many architecture offices might have it too, but at Cobe, it’s like the space itself has an aura. You see it in the people, the working models, the drawings, the pin-ups — it’s something you can almost touch and breathe in. It just influences your vision and taste of the design, it shapes you. I am not making this up. Spend a couple of days there and you’ll understand what I’m talking about. It’s like learning a new language — Cobe’s aesthetic language.

While I was working there, focusing on architectural visualization, I specialized in creating images in any form that spoke Cobe’s language. Combining this with photography and eventually leaning more toward it, felt like a natural progression for both me and Cobe. I don’t see myself as just an architectural visualization specialist, illustrator or photographer — I consider myself a specialist in architectural imagery, of any kind, that aligns with our aesthetic. That’s what I’ve been doing for a long time and it’s what I continue to do.

When I participate in doing images for ongoing projects, there is a big advantage to working closely with the design team. Having collaborated with them hundreds of times, you kind of know what they need, so then you just go and do it. And it clicks. When you work for a long time replicating a certain line of work it becomes almost an instinct. It is all about how the project feels right away. Do you get that immediate “oh yes” feeling when you first see the image? If you do, it means we’ve done our work right.

Is this part of the design process? I absolutely think so. Those images help modify and shape the project, fine-tuning it to look its best. So, yes, I do believe that, in many cases, I’m actively participating in the design process.

The Opera Park by Cobe, Copenhagen, Denmark | Photo by Francisco Tirado | Jury Winner, 12th Annual A+Awards, Public Parks & Green Spaces

KP: How does your background in architecture influence your approach to photography? Conversely, has your experience in photography and visualization influenced your understanding of design?

FT: Since I started studying architecture, I have no idea how many photos of buildings I’ve seen — just like any other architect. And if seeing images in books and magazines wasn’t enough, now with social media we have them in our hands and we’re bombarded with them all the time. In the beginning, I was using all that visual memory purely for design. But all the time I spent looking at architectural images for design references ended up working the other way around too.

When I was working as an architect 15 years ago, I started a habit that I still maintain today. I created a folder of my favorite architectural photos and I keep it running as a random background on all my computers. I store the folder in the cloud, so it’s always updated on every device I use.

Every time I sit at my desk or open my laptop at home, a different building photo appears as my background. I take a couple of minutes to appreciate it, thinking, “Wow, look at those lines,” and then I get back to work. Occasionally, I go back to the folder, review all the images, delete the ones I don’t like anymore and add new ones that match my current taste. When you do this hundreds of times, you end up with an amazingly curated folder of inspirational images. I originally started it to focus on design, but now I keep it going to focus on the aesthetics of buildings. The process remains the same.

I believe when you specialize in architectural photography or architectural visualization, a funny process happens. So, yes, I would say your understanding of the design changes.

When I was working as an architect, I naturally paid a lot more attention to details and the small things — after all, the building has to function properly, right? But when you’re creating images, unless you’re focusing on details specifically, you tend to concentrate more on the big picture. It’s like looking at a building with blurry eyes; you filter out the small noise and focus only on the key elements. I got so used to viewing buildings this way that now, sometimes, it’s hard for me to go back and look into the details that amaze other designers.

The Opera Park by Cobe, Copenhagen, Denmark | Photo by Francisco Tirado | Jury Winner, 12th Annual A+Awards, Public Parks & Green Spaces

KP: Do you have a signature style or approach that people tend to recognize in your work?

FT: I don’t know. I do not have an A B C “filter” that makes my work look a certain way. I actually tried to do it, because I thought that if I wanted to industrialize my process so I could produce more I’ll need to have a standard creative process. But this didn’t work for me.

Instead, I created a personal framework — a solid bracket within which I can experiment and find what works best for each project. I apply all my energy to it, but only within that bracket. You might wonder, what does that framework look like? For example, the way I organize my time and files is very structured. I know exactly how many hours I’ll spend on a particular task, the order in which I’ll work, the references I’ll use and when I finish, I archive everything properly. That way, if I need to revisit a project later, I can get back to work in just a couple of minutes.

This might look like nothing to do with style but it does to me, because it organizes my working day, so I can spend more time at home with my loved ones with whom I recharge my batteries. I won’t be able to produce any images if I don’t spend time with them.

So when I do images, I do know what images I like and how they should look so that they fit Cobe’s universe. But this is a work in progress and the looks of my images change over time while I learn new techniques and get software or hardware improvements.

The Redmolen / Tip of Nordø by Cobe + Vilhelm Lauritzen Architects, Nordhavnen, Copenhagen, Denmark | Photo by Francisco Tirado

KP: Could you share any specific techniques or tools, whether it’s software, camera equipment or post-production processes, that are crucial to your work and to achieving the desired aesthetic?

FT: I do not use a tripod 99% of the time, because it slows down my work a lot. Of course, I use it if it is strictly needed — for instance, when shooting long exposure images or shooting at night or tricky interiors. But the rest of the time I go handheld.

My images aren’t perfect — the sharpness isn’t always 100%, but that’s okay. Most people view images on their phones these days, so ultra-sharpness doesn’t make a big difference.

However, you can’t achieve this with just any camera. My camera has excellent in-body stabilization and I use lenses with built-in stabilization as well. With these two levels of stabilization, combined with holding super still while shooting, it does the trick.

When I visit a location, I normally work from early morning to the evening on the project, following the sun, resulting in me walking a lot. It is like trekking — I carry a couple of sandwiches and water with me (it is very important to be hydrated). My camera bag can get pretty heavy, so what I do is take long walks on random days during my free time, carrying all my gear. This helps my back, legs and shoulders get used to the weight, preparing me for any shoot. It’s like doing a workout in preparation for shooting days.

Regarding post-production, I do not use tilt-shift lenses, I do use very wide-angle lenses on a very high-resolution sensor that allows me to straighten, cut and zoom on the images as much as I want, all done digitally in post-production.

AAU Innovate by Cobe, Aalborg, Denmark | Photo by Francisco Tirado

KP: Back to the World Visualization Festival again! Can you comment on the importance of gathering visualizers to foster discussion at this particular moment, especially in the context of the industry’s rapid evolution and the rise of new technologies like AI in recent years?

FT: I am very happy to be a speaker at the WVF. It was a big surprise for me and I am ecstatic to be able to meet lots of people whose work I admire. Now, I have the chance to see them all in person, all at once, in one place.

I want to add, I do not mean to try to convince anybody to come to the WVF, but you should do it if you work in the industry. The reason is simple: the amount of industry knowledge that’s going to be packed into those three days is equivalent to months and months of individual research — something that, in my opinion, is a waste of time.

When I was starting out, I made the mistake of not staying connected with the community, which led to a lot of misunderstandings about techniques and the business side of things. To be honest, it also cost me a lot of money because I just didn’t know any better.

For everyone who is just starting out and even for those who are more advanced, this event could be a big boost in how they approach their work. It’s also crucial for staying up to date with new technologies like AI and understanding how other professionals — with lots of experience and, importantly, high-profile clients —are already incorporating these tools into their workflows. And I want to emphasize this — important clients — because, at the end of the day, we all do this to make a living.

Coming to the WVF and learning from the best in the industry is worth every second spent there.

If you want to hear more about Francisco’s experiences and insights and learn from other leading experts in the field, be sure to catch his full presentation at the World Visualization Festival in Warsaw this October.