Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

For many, the holidays are a time for togetherness. For me, it is also a time for streaming movies. As a teacher, I am grateful for the days off and the opportunity to unwind in the evening with a cup of peppermint tea and a film. And at this time of year, I don’t go for thrillers. The slower and more ponderous the better.

Luckily, there are wonderful options available on major streaming services for just this type of cinematic experience. In particular, there are a number of great films, both documentaries and dramas, about architecture. The movies listed here are both pleasurable and thought-provoking.

Frank Lloyd Wright (1998)

Available on Thirteen PBS Passport

Entrance to Frank Lloyd Wright Home and Studio in Oak Park, Illinois. Image by Philip Turner, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Ken Burns is in the cultural ether again following the release of his documentary on the American Revolution, a twelve-hour tour de force that has earned accolades for placing the Revolution in its full context, incorporating the often overlooked perspectives of Loyalists, Native Americans, and others. The release of The American Revolution has been particularly notable for drawing attention to the value of public television during a period when it is under attack.

In 1998, Frank Lloyd Wright was given the Ken Burns treatment in a two-part, four-hour documentary that aired on PBS. The film opens, provocatively, with an excerpt of a poem by William Butler Yeats:

The intellect of a man is forced to choose

Perfection of the life, or of the work,

And if it takes the second, must refuse

A heavenly mansion, raging in the dark.

The theory here is that authentic artists are doomed to unhappiness. The obsession that drives them to creative achievement also prevents them from forming lasting relationships. This was true for Yeats himself, and it was even more true of Frank Lloyd Wright. As Burns and co-filmmaker Lynn Novick show, Wright had an erratic personal life that was punctuated by scandal and conflict. One of the key contradictions Burns explores is that between the storminess of Wright’s personality and the tranquility of his architecture.

This documentary is notable for showcasing Wright as an architectural thinker, exploring how his concept of “organic” architecture differed from the “modern movement” of Gropius and Le Corbusier. Wright’s views on urbanism are also represented here at length.

The Belly of an Architect (1987)

Free with ads on Tubi

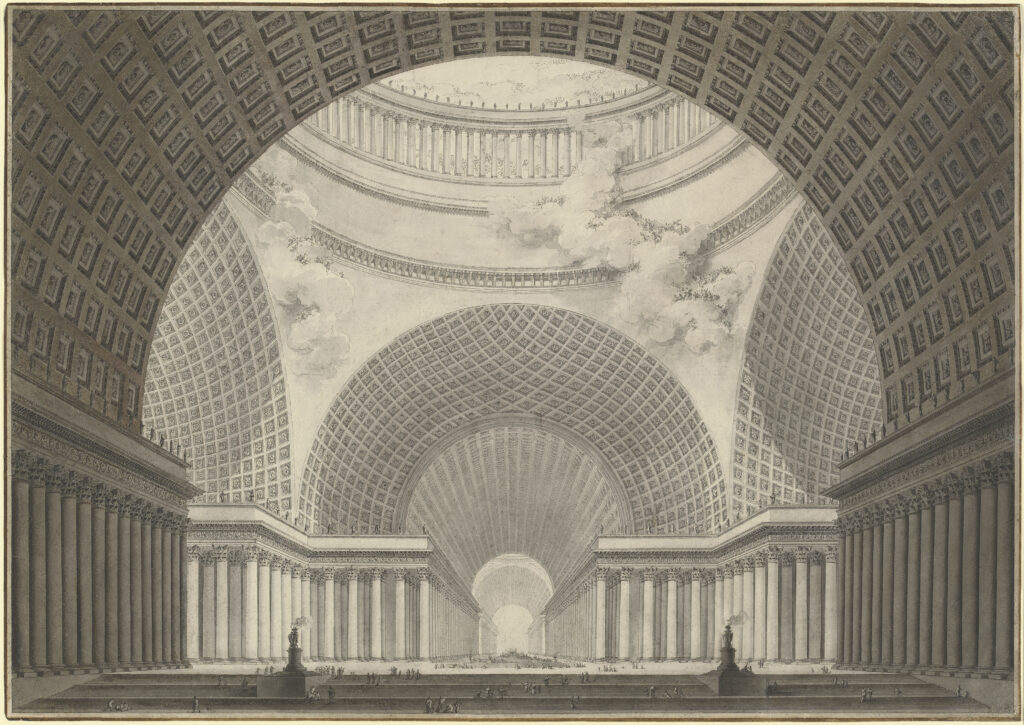

“Etienne-Louis Boullée, Perspective View of the Interior of a Metropolitan Church, 1780/1781, pen and black ink with gray and brown wash over graphite on laid paper, with framing line in brown chalk, overall: 59.4 x 83.9 cm (23 3/8 x 33 1/16 in.), Patrons’ Permanent Fund, 1991.185.1”. National Gallery of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Everyone knows about “feel-good movies,” but what is the term for the opposite? These tend to be the movies I like the best. There is a unique pleasure that comes from spending an hour and a half with a character whose life is falling apart — and then leaving this character and their problems behind once the movie ends. Aristotle called this experience of relief catharsis.

The Belly of an Architect was nominated for the Palme d’Or in Cannes in 1987. It follows an American architect named Stourley Kracklite who is putting together an exhibition in Rome on the 18th-century French architect Etienne-Louis Boullée, a visionary who constructed very few buildings but whose conceptual sketches continue to provoke interesting discussions. The film acknowledges that there was something disturbing, even totalitarian about Boullée’s grandiose and monumental designs. Early on, a character points out that Boullée was admired by Adolf Hitler.

As Kracklite gets deeper into his research, he develops an obsessive fascination with Caesar Augustus, the first emperor of Rome. And like a dictator, he becomes paranoid, and later physically ill as his life begins to unravel. I do not want to spoil the film’s shocking ending, but something of its mood is extremely relatable to anyone who has spent late nights working on an ambitious project in a library or studio.

Sketches of Frank Gehry (2006)

Available to rent on YouTube

Walt Disney Concert Hall by Frank O. Gehry. Los Angeles, California, United States. | Photo by Tobias Keller, Free to Use via Unsplash.

The architecture world is still coming to terms with the legacy of Frank Gehry after his passing this December. Among architects, Gehry’s reputation was singular: by name recognition, he was, at the time of his death, the most famous living architect, and there are no contemporary buildings more famous than his Guggenheim Bilbao. Yet Gehry was not without his detractors. His bold, deconstructivist approach subverted the modernist formula of form over function. He delighted in strange angles, curves, and features that felt playfully out of place.

Sketches of Frank Gehry is the final film to be directed by Sydney Pollack before the great documentarian’s death in 2008. It includes interviews with people who crossed paths with Gehry throughout his life, not just architects but also actors like Dennis Hopper and artists like Julian Schnabel. These discussions, along with interviews with the famously gruff but lovable Gehry, provide a well-rounded picture of the architect who once asserted that architecture was “by definition” a form of “sculpture” — that is, not a machine for living in.

I especially enjoyed the film’s treatment of the first work that brought Gehry notoriety: the deconstructive transformation he carried out on his own Santa Monica home in the 1970s. “The neighbors got really pissed off,” Gehry recounted with delight in a 2022 interview with Dezeen. Gehry’s appetite for provocation is part of his legacy and one of the reasons his designs always felt vital, even once his style became familiar.

Columbus (2017)

Free with ads on Tubi

North Christian Church, designed by Eero Saarinen, Columbus, Indiana. Photo by Carol Highsmith. Public Domain via the Library of Congress

Columbus, Indiana, is an unlikely architectural Mecca. With a population of just over 50,000, it is one of the smaller cities in Indiana. It is also quite out of the way, a full forty miles from the urban hub of Indianapolis. Nevertheless, this town is home to a number of modernist masterpieces designed by Eliel Saarinen, Eero Saarinen, Myron Goldsmith, John Carl Warnecke, and other 20th-century masters. Many of these buildings were commissioned by J. Irwin Miller, a famous patron of modern architecture and the former CEO of the Cummins Engine Company, which is based in Columbus.

Columbus is a quintessential indie drama of the 2010s, not quite mumblecore but subdued. It follows Jon Cho as Jin Lee, a bitter young adult who goes to Columbus when his father, a famous architectural scholar, is hospitalized there after falling ill before a planned lecture. Jin’s relationship with his father was strained, and in consequence he does not care for modernist architecture. But after spending time in the town and developing a friendship with a young architecture enthusiast played by Haley Lu Richardson, he begins to develop an appreciation for the buildings his father loved so much.

The director of this film, Kogonada, allows architecture to play the starring role. The pseudonymous Korean filmmaker made his reputation through visual essays in which cinematic images, not words, tell the story. There is a stillness to this film, a sense of atmosphere, that is palpable. One can almost feel the humidity of the languorous midwestern summer days. Watching the film does not feel so much like following a story as stepping into a world — an effect that only cinema can truly provide.

My Architect (2003)

Available with a subscription to Criterion Channel

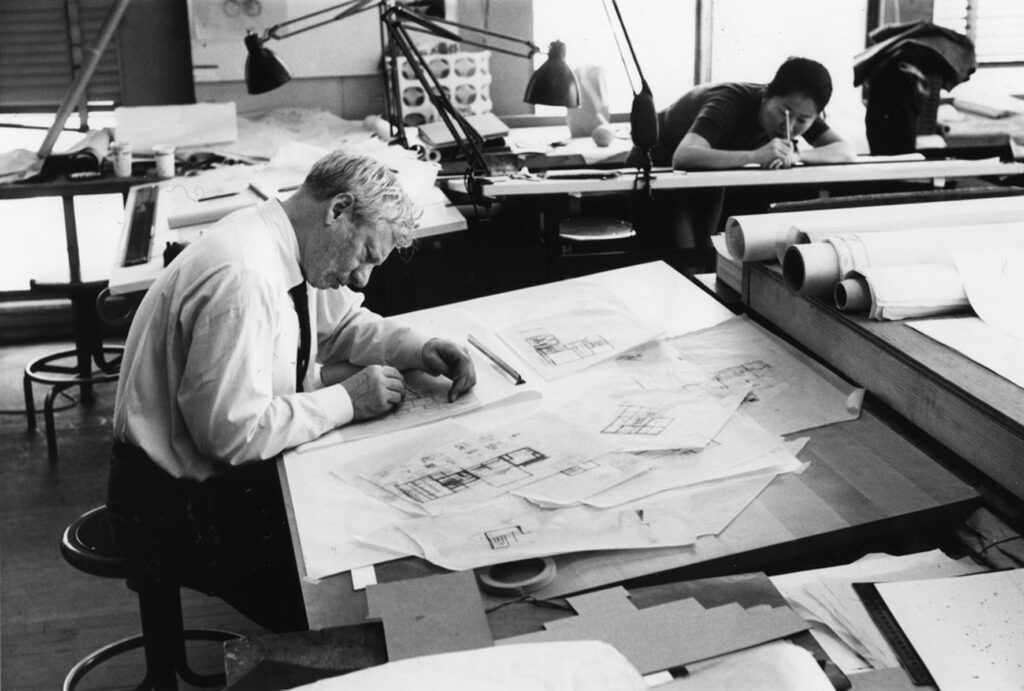

Louis Kahn at work. Image by Forgemind Archimedia, CC 2.0 via Flickr

This is the third documentary I am recommending about a major architect, but it stands apart from the others due to its emotional impact. While the documentaries about Frank Lloyd Wright and Frank Gehry are illuminating, they are not moving, and they certainly aren’t tearjerkers. This one is.

My Architect was directed by Nathaniel Kahn, the son of the famed architect and University of Pennsylvania professor Louis Kahn. When Nathaniel was just 11 years old, his father died of a heart attack in the restroom at Penn Station in New York. The address on his passport was scratched out for reasons that are still mysterious, which made it hard for police to identify the body. The world-famous architect lay in the morgue for three days before his body was claimed.

Louis Kahn was not a good father. Nathaniel’s mother, landscape architect Harriet Pattison, was not Kahn’s wife; she was his mistress, and she also worked for him. Up until the end, Kahn would often tell Pattison that he planned to leave his wife and live with her and their son. (Nathaniel, looking back, has doubts his father was serious about this, but his mother retains her faith). To make matters more complex, Pattison was not the first mistress with whom Kahn had a child. Years earlier, he had a daughter with another one of his employees, the architect and urbanist Anne Tyng, who similarly maintained contact with Kahn throughout his life and harbored hopes about them being together one day. Essentially, Louis Kahn balanced three families, an arrangement that no one seemed to feel good about. His three children did not meet one another until his funeral.

In My Architect, Nathaniel Kahn attempts to piece together who his father really was. How could someone behave so selfishly in their personal life and yet be so generous in their work? Each person Nathaniel speaks with has wonderful things to say about “Lou,” who, during his lifetime, was appreciated as both a lovable bow tie-wearing eccentric and an artist of deep integrity. Master architects, including Philip Johnson, I.M. Pei, Robert Stern, and Frank Gehry, are interviewed, and each one speaks to Lou’s influence and importance. A common theme is that Lou would never compromise his designs to satisfy his clients — a fact that earned him the respect of his peers, but also contributed to the fact that, when he died, he was half a million dollars in debt.

Jatiyo Sangsad Bhabhan, or the National Parliament House of Bangladesh, is considered Louis Kahn’s magnum opus. The complex is one of the largest legislative complexes in the world, covering 840,000 m2 (210 acres). Image: Lykantrop, National Assembly of Bangladesh, Jatiyo Sangsad Bhaban, 2008, 4, CC BY-SA 3.0

The most moving part of the film occurs near the end when Nathaniel visits the National Parliament House in Bangladesh, his father’s magnum opus. The people he meets there speak of his father reverently. While Lou had no prior connection to this country, he visited countless times while working on the project and developed a strong connection with the Bangladeshi people and their political hopes. After all, this was not to be just any building; Lou was building the seat of democracy for a country whose future was still uncertain. (Construction actually took place during the Bangladesh Liberation War. When Lou was hired, Bangladesh was still part of Pakistan.) Lou wanted to create a space where democracy could flourish, a structure that spoke to the country’s bright future more than its conflicted present. All of this is explained to Nathaniel by a Bangladeshi man who cannot hold back his tears when describing what the building means to his country.

My Architect begins as a personal journey but ends as a meditation on the power of architecture to embody the highest aspirations of both individuals and nations. One comes away from the film understanding that Kahn was, above all, a spiritual architect, someone who wanted to move people and even change them through his designs. Though he loved raw surfaces and embraced the modernist gesture of laying bare the structure, his vision was not quite the same as the European modernists. In the film, it is actually Gehry who explains this best during the section when he is interviewed. Gehry describes Kahn as a rebel in an era when modernism was becoming overly formulaic, an imaginative straightjacket imposed on young architects during their education. Unsatisfied with mere minimalism, Kahn aimed to create buildings with poetic resonance — buildings that mattered.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Cover image: Gunnar Klack, Yale-Center-for-British-Arts-New-Haven-Connecticut-04-2014c, CC BY-SA 4.0