Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.

There is something very Hegelian about Rem Koolhaas’s Delirious New York: A Retroactive Manifesto for Manhattan. This is probably why I didn’t understand it when I first read it as an undergraduate.

The Hegelian aspect of this book is right there in the title. The book is presented, paradoxically, as a retroactive manifesto — or an articulation of goals that have already been accomplished. Hegel is famously hard to summarize, but the basic gist — or geist (that is a Hegel joke) — of his thought is that history can be understood as the slow and methodical working through of an idea. For Hegel, that idea is freedom, and importantly for him, this is something that it was not possible for people to understand in an earlier historical moment than his own. (Hegel was writing in the 19th century, on the heels of the French Revolution). “The owl of Minerva,” he wrote, “flies at dusk.” According to Hegel, the meaning of any historical event is only legible after the fact, and it often turns out to be very different from what people believed they were doing — or fighting for — in their own moment.

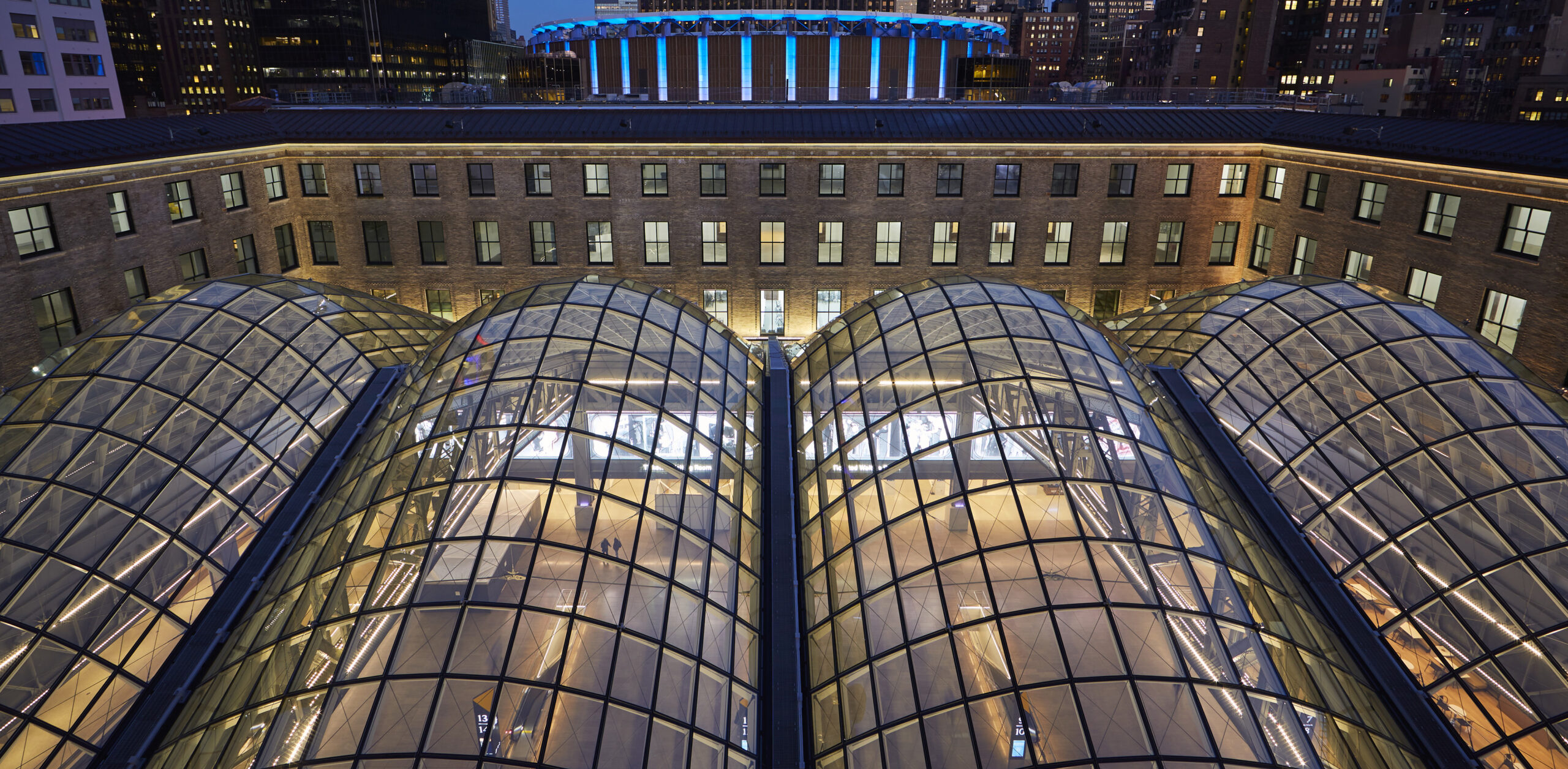

Koolhaas believed something similar about the history of Manhattan. In 1811, when the New York City grid was first proposed, the authors of this plan perhaps only dimly conceived the significance of the scheme. However, by the time Koolhaas wrote his book 1978, it was clear to him what the history of Manhattan essentially was: a working through of the idea of something Koolhaas calls “Manhattanism,” or a “program… to exist in a world totally fabricated by man, i.e., to live inside a fantasy.” He adds that this idea was “so ambitious that to be realized it could never be openly stated.”

The Commissioners Map of the City of New York, 1807. James S. Kemp, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Manhattan, it seems, had a telos: it developed toward a certain end that was present early on in its history, at the dawn of the machine age. In 2023, we might say that it was a testing ground for the anthropocene, or the geological age in which human activity is the dominant influence on climate and the environment. As Koolhaas notes, where nature exists in Manhattan, it is in the form of parks with clearly defined boundaries. You can enjoy nature in Central Park, but it is enclosed on all sides by man-made borders, like animals in the zoo. Manhattan was perhaps the first significant landmass that was carved out in this way, with an understanding that human beings, and not nature, ultimately held total dominion over the landscape, and could shape it according to whatever scheme they wished.

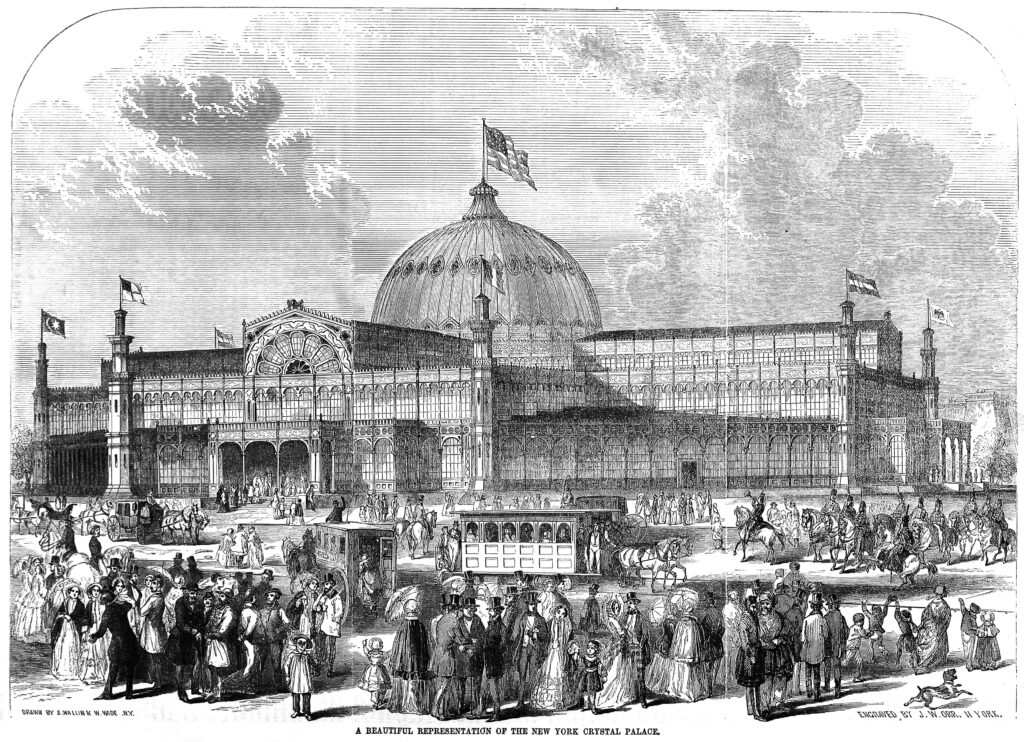

The grid system, to Koolhaas, allows for the simultaneous existence of competing visions of the future, or “utopian fragments.” He writes that “each block is covered with several layers of phantom architecture in the form of past occupancies, aborted projects, and popular fantasies that provide alternative images to the New York that exists.” Like capitalism, the economic system that propelled industrialism in the same period that New York experienced its largest period of growth, the city seems to have always embraced competition as an ethos. Each competing vision of the future received its own little space within the grid. The city was an arena, or stage, for the production of possible futures. Koolhaas’s mission in this book is to narrate at least a few of these possible visions and how they were embodied in architecture.

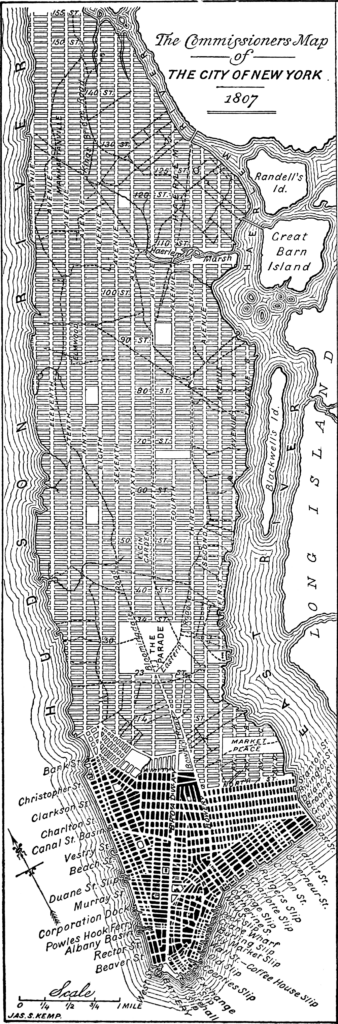

Engraving of the New York Crystal Palace published in 1853. Located in what is today Bryant Park, the Crystal Palace was the site of the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations. Here, the first modern elevator was exhibited by Elisha Otis. S. Wallin and W. Wade, artists; J. W. Orr, engraver, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

This, at least, is the drift of Koolhaas’s book. He believes that Manhattan represents something important about the heroic ambition and ultimately tragic destiny of the modern world. He describes himself as Manhattan’s “ghostwriter,” noting sardonically that his “source and subject passed into premature senility before its ‘life’ was completed.” Here it must be remembered that Manhattan, in the 1970s, was experiencing a series of crises. Crime, bankruptcy and racial conflict marked the city, in the eyes of the American public, as a failure. The picture improved somewhat in the 1990s, but in recent years New York once again has faced a number of crises, leading many across the nation to wonder if hyper-density offers a desirable vision of life. Also relevant: at the same time Manhattan recovered, many other American metropoles, including Detroit, declined, suffering from economic devastation and population loss.

The question must be posed: is America’s future an urban one or a suburban one? The latter is arguably worse for the environment — hyperdensity has its benefits when it comes to carbon emissions. But the latter is utopian in its own way. The idea of every American owning their own home, their own plot of land, has a certain postwar charm. It makes sense that many are nostalgic for this vision in a period when housing and food costs are skyrocketing, causing Americans to regard the future with dread. It is easy to critique the American tendency to crave more space — freedom from noise and the crowd — but it is also easy to understand it. We all want to see the crowds the way Walt Whitman saw them, as “the great rondure, the cohesion of all, how perfect!” But sometimes people get tired of having their toes crushed on the subway.

Built decades after the publication of Koolhaas’s book, The High Line represents New York’s ability to adapt existing infrastructure to new needs. Jakub Hałun, High Line, New York City, 20231001 1806 1489, CC BY 4.0

However, something of Whitman’s love for urban crowds, for New York City, must be recovered if America is to heal its current political, cultural and ethnic divisions. The most inspiring aspect of New York City is indeed its density, the fact that so many people, from so many backgrounds, are able live so close together in relative peace and harmony. Something of this possibility, according to Koolhaas, was latent in the original design of the Manhattan grid, and through the centuries the gamble has paid off more successfully than many would have assumed.

45 years after its original publication, Rem Koolhaas’s book remains a source of inspiration. As someone who grew up in the New York City metro area and spent much of his young adulthood in Brooklyn and Manhattan, the book was an interesting opportunity to see a familiar place through the eyes of an outsider. (Koolhaas, of course, is from the Netherlands). Loose in structure, playful in tone, and ambitious in scope, Delirious New York introduced the world to Rem Koolhaas years before he ever completed a significant building. It is well worth revisiting today.

Cover Image: DigbyDalton, Manhattan and the Central Park from the Empire State Building, CC BY-SA 4.0

Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.