Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.

Architects see buildings differently than non-architects. This isn’t just a truism, it was the finding of a 2022 study published in the Journal of Environmental Psychology titled “Psychological Responses to Buildings and Natural Landscapes.”

For the study, a team of researchers led by psychologist Adam B. Weinberger surveyed people from various walks of life, measuring how they judged both built and natural environments according to three aesthetic dimensions: coherence, fascination and hominess. They found that architects value coherence far more than laypeople, who sometimes vibe with fascination (or complexity) but are most attracted to hominess in the built environment.

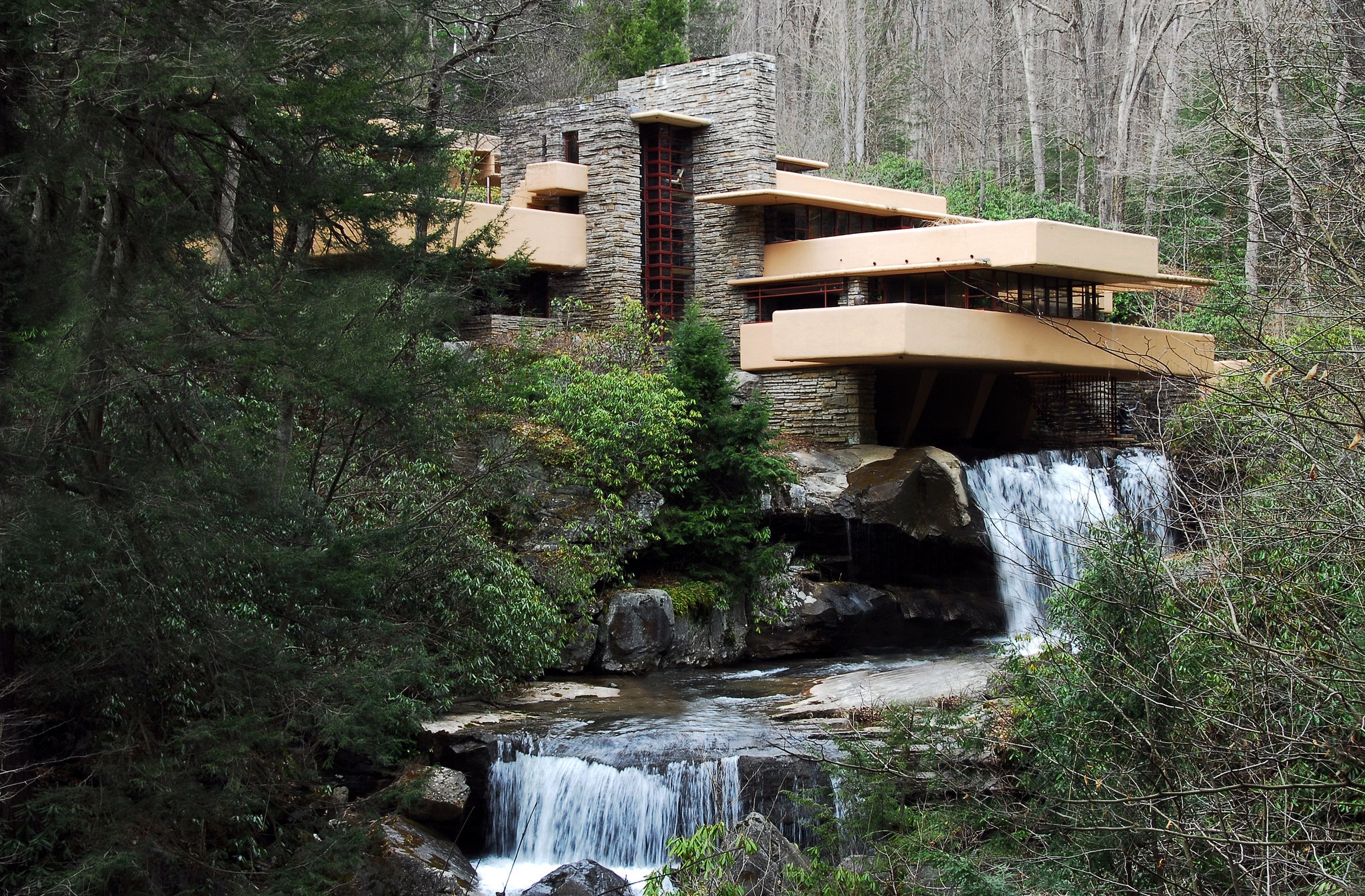

In fact, lay people in the study often described spaces that were too coherent as cold and intimidating, or in other words, not homey enough. One of the study’s authors, Professor Anjan Chatterjee of the University of Pennsylvania, even admitted to feeling this way when he visited Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater as a young man. “Even as I admired Mr. Wright’s masterful construction, I felt a subtle resistance,” Chatterjee explains in Psychology Today. “My discomfort was a reaction to his all-encompassing control of the space.”

Fallingwater by Frank Lloyd Wright, PA, United States. Image via Architizer media library. Creative Commons.

The authors of this study concluded that architects need to do better in understanding the aesthetic preferences of their clients, who react differently to built spaces than they do. “Knowing that architects value coherence more than lay people provides a point of conversation,” Chatterjee says. “Such conversations are important if architects are to promote the well-being of people who will inhabit the spaces they design long after they have moved on to new projects.”

If you are an architect, that last statement perhaps made you bristle. It seems reminiscent of the old chestnut that “regular” people prefer “old” buildings that “blend” into their surroundings, as opposed to “modern” buildings that feel like they are “imposed” on the environment. (Apologies for the scare quotes). This narrative, often politically conservative in character, is trotted out time and time again by self-described “classicists” including, notably, King Charles III.

In 2020, then US President Donald Trump actually tried to ban the use of modern architecture for public buildings by means of an executive order. The edict claimed that since the 1950s, “the government has often selected designs by prominent architects with little regard for local input or regional aesthetic preferences. The resulting Federal architecture sometimes impresses the architectural elite, but not the American people who the buildings are meant to serve.” Trump’s argument could not have been clearer: in order to bridge the gap between architects and the public, architects must return to older styles.

As a lover of contemporary architecture and someone who (I hope) appreciates “coherence” more than Donald Trump, I am mostly opposed to the arguments of classicists. And yet, I must admit that there is a germ of a point buried under their reactionary bluster.

Zaha Hadid’s Heydar Aliev Center is an icon of contemporary architecture. But does it really speak to its environment in Baku, Azerbajian? Image via Architizer Media Library.

There is a way in which the rise of modern architecture corresponded with a decline in regional flavor, especially in major cities. The landmarks of contemporary architecture — Bilbao, Heydar, etc — might be magnificent, but they don’t speak to their setting the way, for instance, the Duomo of Florence does. These are buildings that could really be placed anywhere.

Luckily, the solution to this problem doesn’t have to be going back to the past and “reviving” local styles. Since the 1980s, architects associated with the Critical Regionalist movement have tried to thread the needle between respecting the past and remaining oriented toward the future. The architects associated with this style are not revivalists — their buildings are undeniably modern, not retro — but they do pay close attention to the environment, designing buildings that are both visually and culturally responsive to what surrounds them.

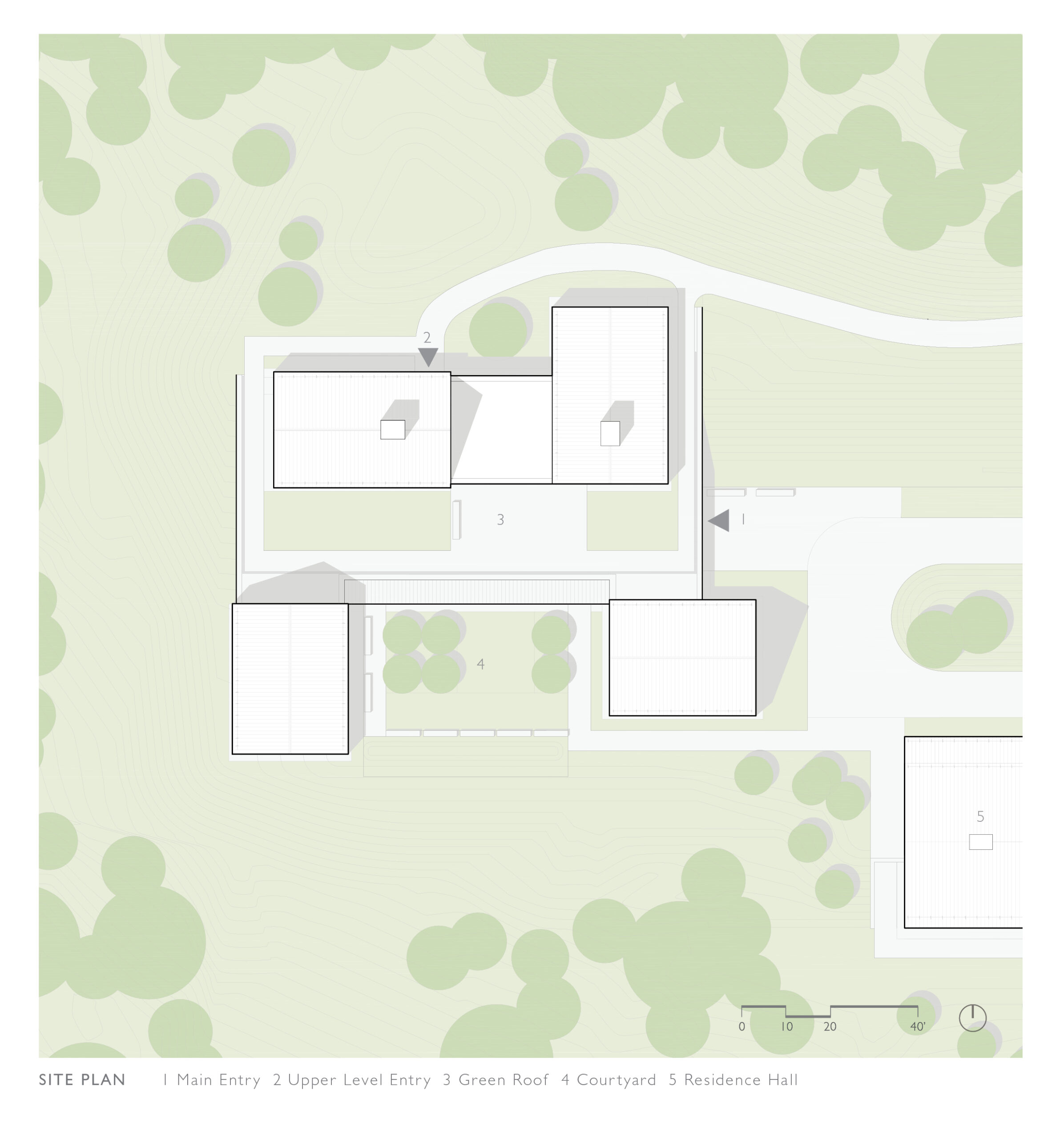

Marlboro Reich Music Hall in Marlboro, Vermont. Image via Architizer Projects.

A beautiful example of Critical Regionalism is Marlboro Music Reich Hall, winner of the 2023 A+ Jury Award in the Higher Education and Research category. This stunning yet subtle project was developed by the Boston based firm HGA. With its pitched roofs and wood exterior, this music hall is very reminiscent of the New England farmhouse style structure it replaced. And yet, it makes no attempt at appearing vintage and thus avoids falling into a kind of retro kitsch. Every detail of this project reflects the architects’ profound respect for the site, the former campus of Marlboro College in Vermont, which is now managed by the Marlboro Music Festival.

“Since 1951, generations of the world’s most talented classical musicians have come together to participate in Marlboro Music, a non-profit, seven-week summer festival where young musicians collaborate alongside renowned artists in an environment removed from the pressures of performance,” HGA explains in the project brief. “Marlboro Music encompasses not only music, but a communal way of life where musicians, staff, spouses, and children share meals, chores, and social events. Participants have included such celebrated musicians as Yo-Yo Ma, Pablo Casals, pianist Mitsuko Uchida, and violinist Joshua Bell.”

HGA strove to emulate the earlier structures and blend in with the other campus buildings. “The design for Reich Hall was inspired by a Cape Cod cottage—a 400-year-old typology derived from 17th-century English settler’s dwellings in New England and the primary inspiration for Marlboro College’s centuries-old buildings,” HGA explains.

And yet, the overall plan is both more complex and multi-functional than anything constructed in New England 400 years ago. In fact, the building’s responsiveness to the landscape, rather than just the history of the site, root it in the 21st century as firmly as the 17th: “The four pitched-roof forms step down with the natural slope of the landscape, with the upper and lower levels organized around south-facing outdoor “rooms” that provide space for community gathering.”

As this is a music hall, no effort was spared to maximize acoustic quality. But this was done without interfering with the aura of the space. In the rehearsal rooms, “a pattern of reflective and absorptive elements — wood panels and glass — maintain a sense of simplicity while optimizing mountain views and allowing natural light to fill the space.”

Reich Hall is not a structure that jumps out and grabs you by the collar, forcing you to confront its modernity. Some buildings are that way and we love them for it, but that style was not right for the site, which is why HGA reached for an approach rooted in Critical Regionalism. The result is a building that seems almost effortless, a natural extension of the campus, but one that is also thoroughly marked by the modern architectural virtue of coherence.

Reich Hall is not a structure that jumps out and grabs you by the collar, forcing you to confront its modernity. Some buildings are that way and we love them for it, but that style was not right for the site, which is why HGA reached for an approach rooted in Critical Regionalism. The result is a building that seems almost effortless, a natural extension of the campus, but one that is also thoroughly marked by the modern architectural virtue of coherence.

Architizer's 14th A+Awards judging is live! Subscribe to our Awards Newsletter for updates on Public Voting and the big winner reveal later this spring.