Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

On a recent episode of the podcast Why Theory? — which I often enjoy in headphones while washing dishes — University of Vermont Professor Todd McGowan described the Austrian philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein as “maybe the smartest person who ever lived.”

This perspective on Wittgenstein is not unique. When still in his twenties, Wittgenstein put forward a critique of a paper by his teacher, Bertrand Russell. The latter — one of the most famous philosophers of the 20th century — claimed that his student’s criticism immediately exposed the limits of his own intelligence.

“I saw that he was right,” Russell wrote to an acquaintance, “and I saw that I could not hope ever again to do fundamental work in philosophy.” Russell devoted the remainder of his life to political activism.

An architect, faced with these anecdotes, will have two questions. One, what were this guy’s philosophical ideas? And two, would he have been any good at designing buildings?

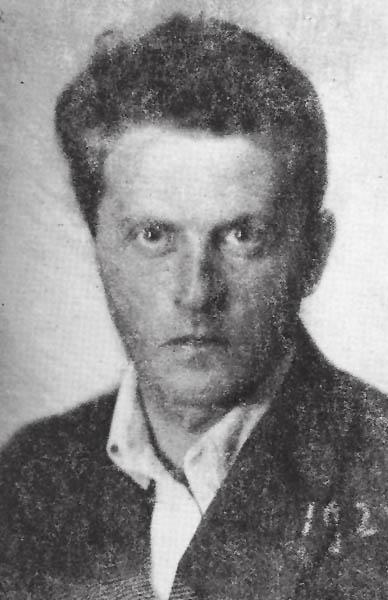

Wittgenstein intimidated those he came into contact with. His life was marked by solitude and intense intellectual ambition. Wittgenstein in 1925 via Wikimedia (public domain)

Luckily, the second question can be answered — and not just in the conditional tense. Unlike almost every other philosopher, Wittgenstein actually did design a building, a family home that still stands in Vienna today. (The first question is much harder, obviously, but perhaps I’ll take a partial stab at that one too…)

The story of Haus Wittgenstein is impossible to appreciate without an understanding of Wittgenstein’s life, which was characterized above all by loneliness and misunderstanding.

Ludwig Wittgenstein was born in 1889 in Vienna, the son of Karl Wittgenstein, one of the wealthiest men in the world, known in his day as the Austrian Andrew Carnegie due to his dominance of the European steel industry. Ludwig was the youngest of nine children, and grew up in an intensely cultured atmosphere. Auguste Rodin, Gustav Mahler, Gustav Klimt and Johannes Brahms were just a few of the famous names that frequently visited the Wittgenstein home at dinnertime.

Despite their immense privilege and the stimulating atmosphere of their childhood, the Wittgenstein children were not happy. Brahms noted the icy way the family interacted with each other, remarking that “they seemed to act towards one another as if they were at court.” Competition between the siblings was intense, especially in the realms of academics and music.

Ludwig’s sister, Margaret, painted by family friend Gustav Klimt. Margaret commissioned the design of Haus Wittgenstein. Gustav Klimt artist QS:P170,Q34661, Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, 1905, CC BY-SA 4.0

Tragedy first struck the Wittgenstein family in 1902, when the eldest brother, Hans, died under mysterious circumstances in America, most likely due to suicide. Two of Ludwig’s other brothers would go on to commit suicide as well.

Ludwig’s turn to philosophy came during college, at the very time he was dealing with these personal losses. Originally, he went in for engineering, but his study of mathematics led him to more theoretical speculations. After reading Russell’s Principia Mathematica, he experienced what he described as a “constant, indescribable, almost pathological state of agitation.” To resolve it, he needed to go to the source, so he traveled to Cambridge University to study philosophy under Russell.

Wittgenstein’s first major work of philosophy came out in 1922. Tracatus Logico-Philosophicus is truly unique, not just from a philosophical perspective, but from a literary one. Instead of constructing an argument in the traditional sense, Wittgenstein assembled 525 declarative statements according to a hierarchical system. Summarizing the contents of this book is beyond the scope of this article — and my competence — so I will content myself with reproducing his final proposition: “Whereof one cannot speak, thereof one must be silent.”

In essence, Wittgenstein was, with the Tracatus, attempting to put an end to philosophy itself: the seductive practice of attempting to answer unanswerable questions. His position was not dissimilar to one taken by Stephen Dedalus, James Joyce’s younger alter ego in Ulysses, which was also released in 1922. In an early chapter, Stephen asserts that he “fear[s] those big words, which make us so unhappy.” In a similar spirit, Wittgenstein said the task of philosophy was to “show the fly the way out of the fly bottle.” His idea was to liberate readers from fruitless questions so that they could move on to more productive endeavors, and stop repeatedly crashing against the glass.

The relationship between this point of view and modernism should be clear. In architecture, as in literature, music and the visual arts, modernism was, in essence, an attempt to clear away the dead weight of the past and make way for the emergence of the “new.” It is fitting, then, that Wittgenstein, when he turned his attention to architecture in the 1920s, would embrace the modernist style — and would do so in a way that was fundamentally uncompromising.

Walter Anton, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain)

Haus Wittgenstein was commissioned by Ludwig’s sister, Margaret Stonborough-Wittgenstein, who asked the architect Paul Engelmann to design a townhouse for her and her family. In April 1926, she asked her brother, Ludwig, to assist in the design, in part to distract him from a painful scandal. (While working as a primary school teacher, Wittgenstein had hit a student so harshly he collapsed. He was not an easy person to get along with.)

Wittgenstein, as one might surmise, was not content to simply assist in the design of his sister’s townhouse. As he told a friend, “ “I am not interested in erecting a building, but in […] presenting to myself the foundations of all possible buildings.” What could be more modernist than that?

During the design and construction of the building, Wittgenstein was almost impossible to work with, repeatedly angering contractors. Again, what he sought was not a functional living space, but the Platonic ideal of a house.

“Wittgenstein applied his engineering skill to even the smallest details so that everything worked beautifully and every fitting was self-evidently part of the house,” explains Edwin Heatcote in a 2013 Financial Times article. “The openings are simply punched into a white membrane façade. Moldings are absent, columns are crowned, not with a capital, but with a negative, a recessed, reduced girth. Walls stop cleanly at ceiling and floor in the kind of perfect junctions that skirtings and cornices would normally have concealed. With every surface exposed and every joint foregrounded, there was no margin for error in construction. In one story, a metalworker queried whether one millimeter here or there would really make such a difference. ‘Yes!’ the philosopher roared before the man had finished his sentence.”

The doors and windows, in particular, were designed with an obsessive attention to detail. “Simple bent brass tubes are used as handles, but are fitted directly into the steel doors, with no covers or faceplates, just as keyholes are cut directly into metal doors,” says Heathcote.

“There is no room for movement or for shoddy workmanship. The windows feature slender steel mullions, which emphasize the height of the rooms while the reductive nature of all the fittings means that the eye is absorbed in the space and light, not the detail.”

The cold and geometric facade of the house gives little hint of the obsessive designing that went into it. Hundreds of proposals were thrown out during the design process. Public Domain Via Wikimedia Commons.

Haus Wittgenstein was completed in 1928. It did not satisfy anyone. Wittgenstein’s elder sister, Hermine, wrote, “Even though I admired the house very much, I always knew that I neither wanted to, nor could, live in it myself. It seemed indeed to be much more a dwelling for the gods than for a small mortal like me”. The philosopher’s brother, Paul Wittgenstein, agreed, as did Margaret, who commissioned the project in the first place.

Margaret eventually sold the property. Ludwig himself was not offended, remarking that it had “good manners” but “no primordial life or health.” The house remains as a landmark in Vienna and receives many visitors per year. They are often perplexed at whether they should consider the structure a triumph or a failure.

Is Haus Wittgenstein too austere, a dwelling for “the gods” rather than human beings? And is modernism, with its commitment to rationalist principles, somehow inhumane? Does Haus Wittgenstein ironically fall into the trap that Wittgenstein identifies for philosophy; that is, does it place impossible demands on its inhabitants, “trapping” them like a fly inside a bottle? And again, what does this say about modernism? Do we actually want “machines for living in” — to quote Le Corbusier — or do we desire something else, something that is intangible, irrational and ineffable? And if we, in fact, desire this, should we? Why do our desires always fall short of — or exceed – the parameters of our intellect? What is wrong with us?

These questions would have been amply familiar to Le Corbusier and the other scions of high modernism. Wittgenstein saw that this problem was bigger than architecture. But he also saw that it couldn’t be answered without architecture — that is, without building something new.

Cover Image: Aldo Ernstbrunner, Haus Wittgenstein, CC BY-SA 3.0 AT <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/at/deed.en>, via Wikimedia Commons

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.