The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

February is Black History Month. This is a time to observe and celebrate the achievements of blacks and the central role that African Americans have played in the United States. It also provides an opportunity to reflect on America’s past as a nation built upon the institution of slavery and racial tyranny that has and continues to disenfranchise African Americans to this day. Across all facets of American society, people of color have been faced with innumerable obstacles to overcome in order to secure the concept of the “American Dream”.

The architecture industry has itself long been a homogeneous space, dominated by white men. African Americans have historically been deprived of exposure or completely barred from the craft altogether. Higher-education institutions and firms often excluded individuals entirely based on race alone.

Norma Merrick Sklarek in the office of Gruen Associates; image via SOM

The existence of black architects today is part of an arduous and continuing process, fueled by gradual socio-political change. However, progress has mainly been due to pioneering individuals whose brilliance, belief and bravery saw them overcome the many barriers that were in their way. Through them, some of the world’s most admired structures were created. Early black architects set the foundation for future generations, through which their legacies live on.

The 9th Annual A+Awards — currently open for entries — is proud to have assembled a diverse jury, including the likes of Natsai Audrey Chieza, Christian Benimana and Kimberly Dowdell, three black industry leaders and strong advocates for greater equality in the profession. Below is a collection of some of America’s most notable black architects over time and those who are still making their mark.

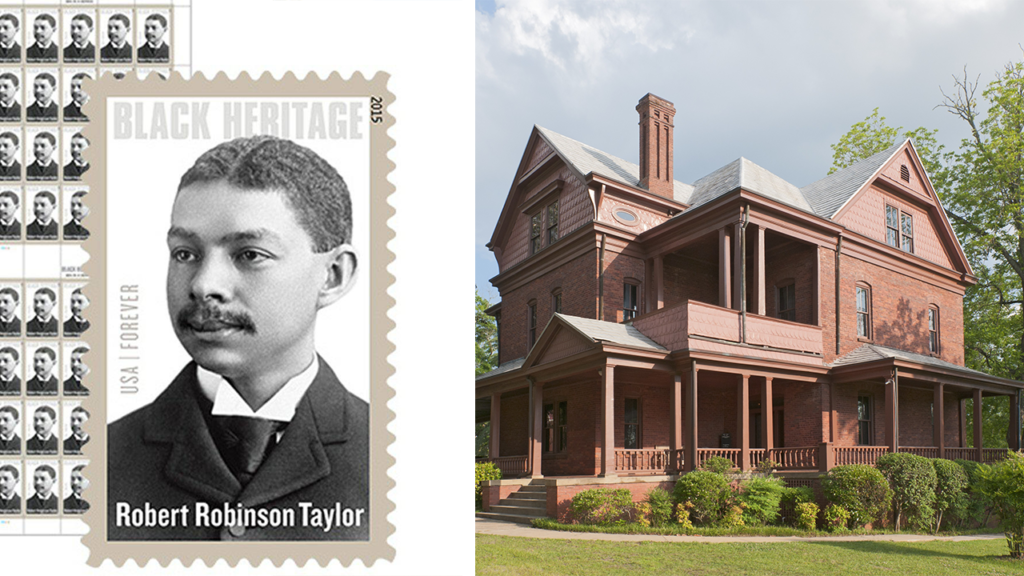

Left: Architect Robert Robinson Taylor on the 2015 Black Heritage Stamp Series and Left: one of his projects; images via U.S. Postal Service and Getty Images/Stephen Saks

Robert Robinson Taylor

Robert Robinson Taylor was the first academically trained and credentialed black architect in America. He grew up in North Carolina where he worked as a carpenter and foreman for his father, Henry Taylor, who was a former slave. Taylor attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, becoming the school’s first black graduate. While a student, he met Booker T. Washington, who later recruited him to lead the industrial program and campus expansion of the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama.

The institute is an African American vocational school that is now a designated National Historic Site. Over the course of his career, Taylor designed more than 25 buildings on the Tuskegee campus, along with libraries, housing, museums, and other academic buildings across the United States. He also laid out architectural plans and devised a program in industrial training for the Booker Washington Institute in Kakata, Liberia.

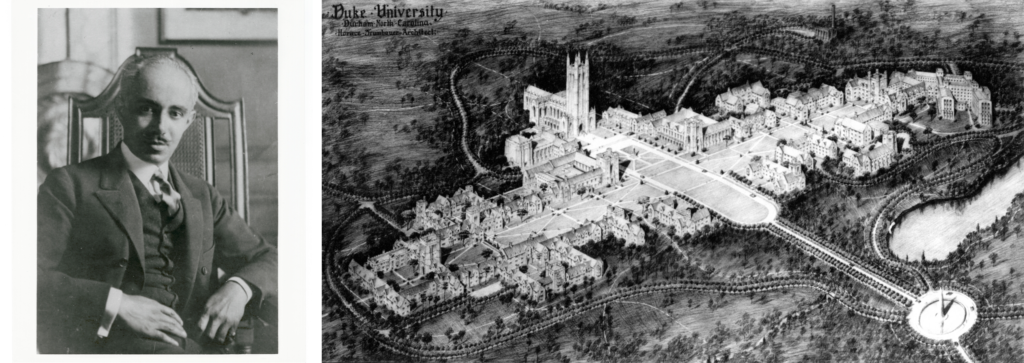

Left: Julian Abele. Right: his rendering of Duke University campus; images via Duke University Archives and University of Pennsylvania Archives

Julian Abele

Julian Abele was the first black graduate of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania in 1902. He spent his entire career as the chief designer at the Philadelphia firm led by Gilded Age architect, Horace Trumbauer. Abele was working for Trumbauer when they received a commission to expand the campus of Duke University, a whites-only institution at the time.

He was the primary designer of the West Campus of Duke University, and his original architectural drawings for Duke have been described as works of art. Due to his firm’s policy of forgoing individual signatures on blueprints and plans, it’s been difficult to identify the full scope of his work. It wasn’t until after his death in 1980 that Abele’s work was recognized by Duke. In 2016 the university renamed a campus quad after the influential architect.

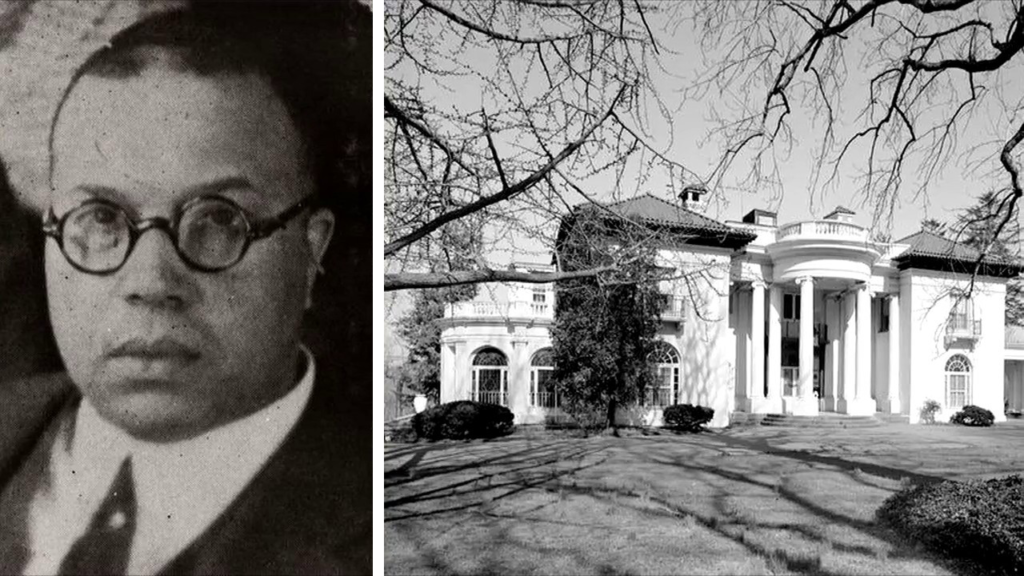

Left: Vertner Woodson Tandy. Right: Villa Lewaro home for Madam C.J. Walker; images via The Library of Congress

Vertner Woodson Tandy

Vertner Woodson Tandy is a lot of firsts. He was the first registered black architect in New York State, the first black architect to belong to the American Institute of Architects (AIA), and the first black man to pass the military commissioning exam. Tandy, while attending Cornell University, was also a founding member of the nation’s oldest African American fraternity, Alpha Phi Alpha.

As an architect, Tandy designed the 1910 St. Philip’s Episcopal Church in Harlem, the first black Episcopal church in New York. He also designed the 1918 Villa Lewaro for black self-made millionaire and cosmetics entrepreneur, Madam C.J. Walker. The Georgian-style residence is considered his masterpiece.

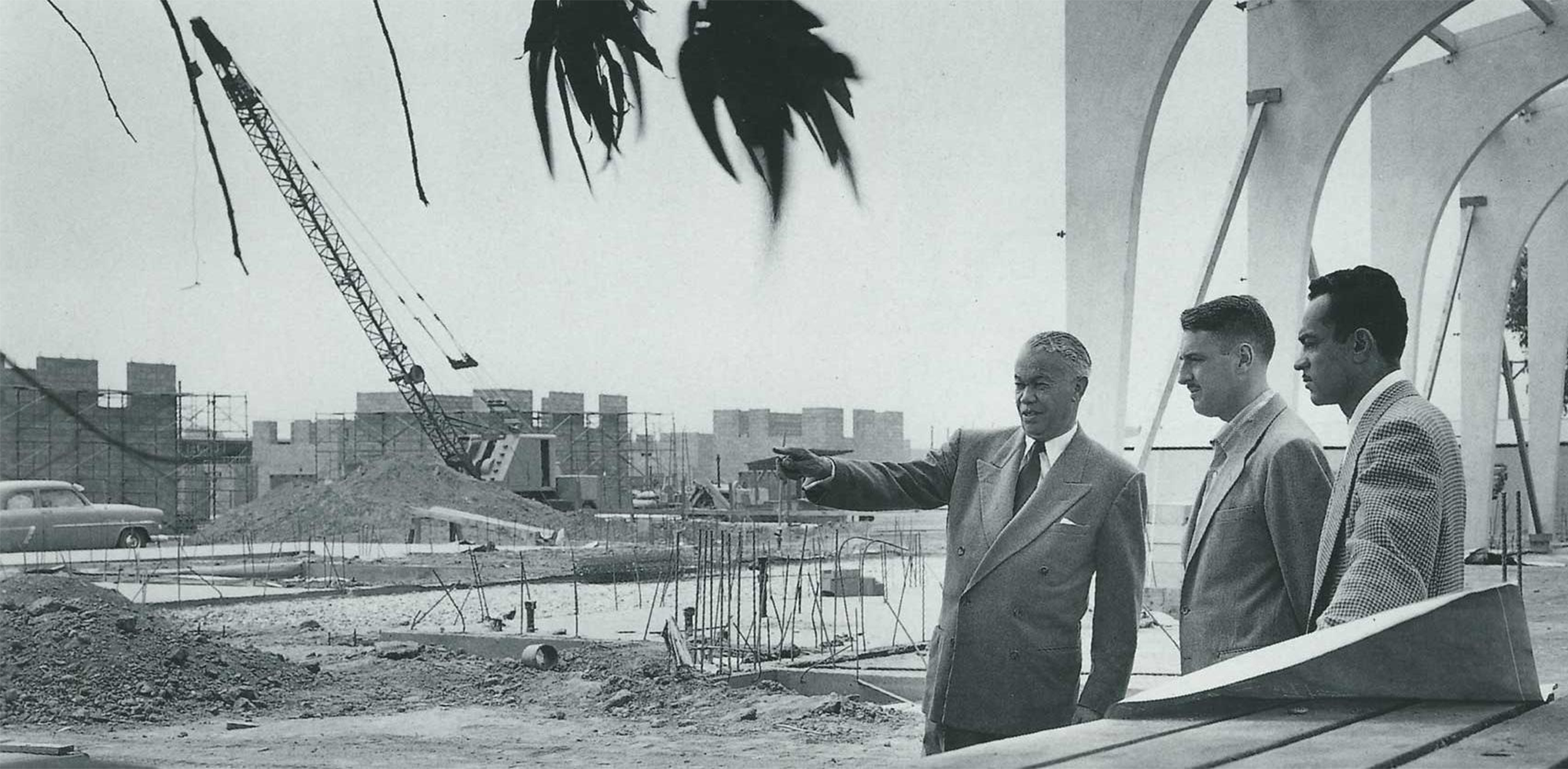

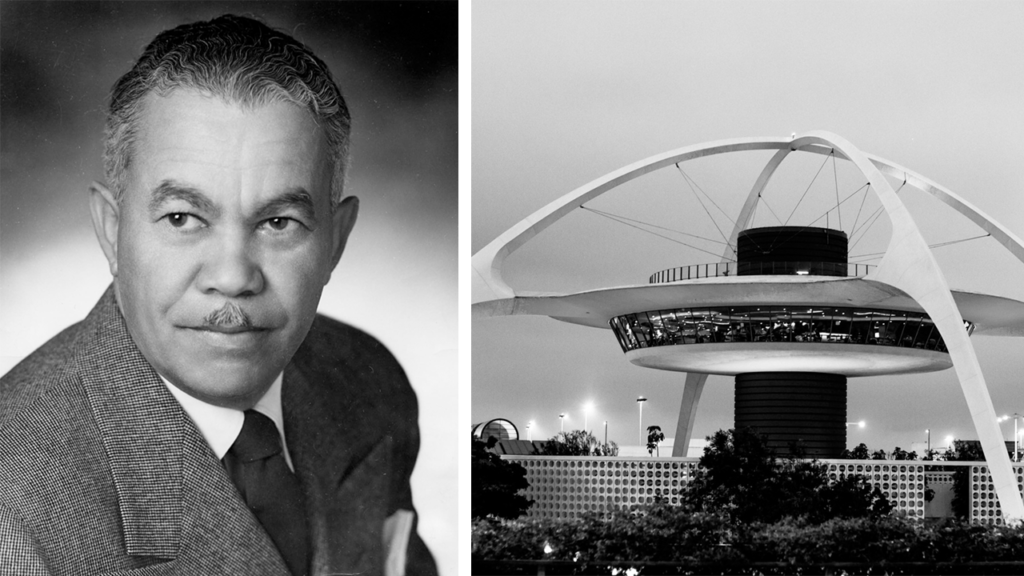

Left: Paul Revere Williams. Right: LAX Theme Building; images via American Institute of Architects and Flickr user thomashawk

Paul Revere Williams

One of the most well-known black architects, Paul Revere Williams’ 50-year career and over 2,000-designed homes has played a major role in shaping Southern California’s signature architectural style. His work is distinguished by a mix of styles and types, from hotels and restaurants to churches and hospitals. Williams studied architecture at the Beaux-Arts Institute of Design and trained at several prominent Los Angeles firms before starting his own practice. He became the first black member of the American Institute of Architects in 1923.

Also known as the “architect to the stars”, Williams designed the homes for an array of celebrity clients, including Desi Arnaz, Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra and Barron Hilton. He defined the spaces that comprise the aesthetic of “Hollywood glamour”, which spread across the country. Williams is also the mind behind the iconic, space-aged Theme Building at the Los Angeles International Airport. Despite the countless barriers Williams faced due to the color of his skin, he remained steadfast and determined as an architect. He even learned how to draw upside down so he could position himself across the table from white clients who were uncomfortable sitting next to him when reviewing plans. In 2017, Williams was posthumously awarded the AIA Gold Medal.

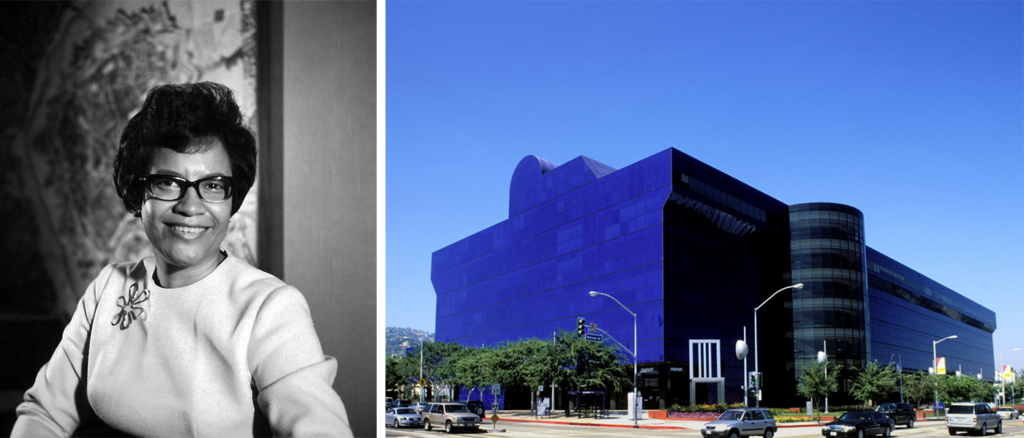

Left: Norma Merrick Sklarek. Right: Pacific Design Center; images via Pioneering Women and Getty Images/Education Images

Norma Merrick Sklarek

Norma Merrick Sklarek was the first major African-American woman architect, a true trailblazer. Her best-known projects, including Terminal One at the Los Angeles International Airport (LAX) and the Pacific Design Center, reveal an idiosyncratic sense of line and color. Sklarek once illuminated the challenges she faced entering the profession, saying: “The schools had a quota and it was obvious, a quota against women and a quota against blacks. In architecture, I absolutely had no role model. I am happy today to be a role model for others that follow.”

Left: Moses McKissack. Right: National Museum of African American History and Culture; images via Tennessean and Getty Images/George Rose

Moses McKissack III

The grandsons of a trained builder and African-born slave, Moses McKissack III and his brother Calvin became the first and second (respectively) black architects licensed in their home state of Tennessee in 1922. Together, they formed McKissack and McKissack, the nation’s first black-owned architecture firm, and the oldest still in operation today. In 1942, they won a multi-million-dollar federal contract to design the Tuskegee Army Airfield, which was the largest project that had been awarded to a black-owned firm to that date. Today, the firm is known for its design and construction management, with one of its most recent and notable projects being the National Museum of African American History and Culture, designed by architect David Adjaye.

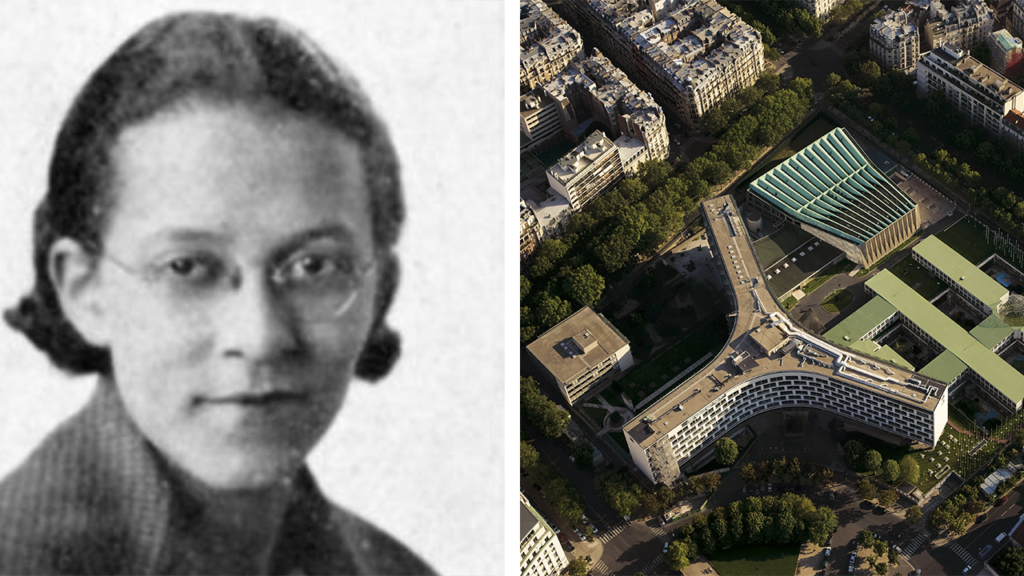

Left: Beverly Loraine Greene. Right: UNESCO Headquarters; images via Illinois Distributed Museum and Getty Images/Yann Arthus-Bertrand

Beverly Loraine Greene

Architect, engineer, and urban planner Beverly Loraine Greene became the first black female architect licensed in the United States, in Illinois, in 1942. She started her career in Chicago with the Chicago Housing Authority, but moved to New York City, as a result of racial prejudice and a subsequent lack of work. In New York, she worked on the Stuyvesant Town housing project, which at the time in 1945 barred African Americans from living in its apartments. Greene went on to work with some of the most renowned international modernists, including Edward Durell Stone on the Sarah Lawrence College arts complex and Marcel Breuer on the UNESCO Headquarters in Paris.

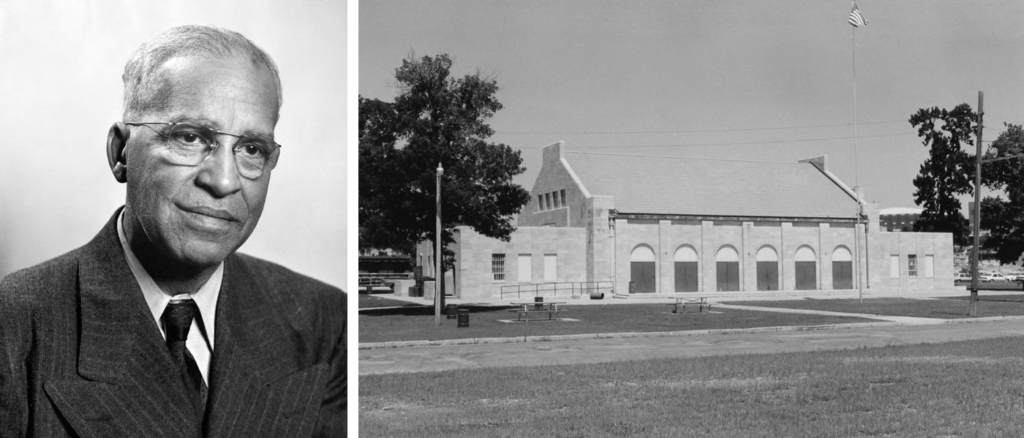

Left: Clarence Wesley ‘Cap’ Wigington. Right: Harriet Island Pavilion; images via Curbed

Clarence Wesley ‘Cap’ Wigington

Clarence W. ‘Cap’ Wigington was the first registered black architect in Minnesota and the first black municipal architect in the United States. Wigington was raised in Omaha, Nebraska, which is where he developed his architecture skills. He served as an apprentice under Thomas Kimball, a renowned local architect and future AIA president. Wigington opened his own practice in Omaha in 1908, but relocated to St. Paul, Minnesota in 1914 due to increasing racial resentment.

By 1917, he had become the city’s senior architectural designer, producing an extensive body of civic work for the city throughout the first half of the 20th Century. He designed schools, fire stations, park structures, municipal buildings, and other notable landmarks in St Paul. Wigington’s lasting legacy remains, with nearly 60 buildings still standing.

Left: Allison Grace Williams. Right: August Wilson Center for African American Culture; images via African American Design Nexus and Joshua Franzos Photography

Allison Williams

Over the course of her decades-long career, Allison Williams has worked on many major projects at some of the world’s most high-profile firms, including San Francisco’s Perkins+Will and AECOM, where she currently serves as the Design Director. Her best-known buildings, including the August Wilson Center for African American Culture in Pittsburgh, illustrate her commitment to maximizing the potential of the site. The August Wilson Center, for instance, is spacious, open and luminous despite the fact that it is situated on a tight street corner.

Right: Barnard Environmental Magnet School; images via Roberta Washington Architects

Roberta Washington

Established in 1983, Washington’s firm is driven by an architectural approach guided by choice in how we live, learn, heal and connect the past to the future. Working on projects that range from affordable housing, educational, cultural and healthcare, Roberta Washington Architects is one of the few African-American, women-owned architectural firms in the country.

Washington has had a multifaceted career, working internationally as a designer in Maputo, Mozambique, and serving as past president of the National Organization of Minority Architects, and is currently a Center for Architecture Foundation board member. She was made a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects in 2006 in recognition for her wide-ranging, impactful career.

The latest edition of “Architizer: The World’s Best Architecture” — a stunning, hardbound book celebrating the most inspiring contemporary architecture from around the globe — is now available. Order your copy today.

Written by Nathan Bahadursingh with contributions from Pat Finn for passages on Norma Merrick Sklarek and Allison Williams, and Kweku Addo-Atuah for the passage on Roberta Washington