Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Architecture is… of all the arts that closest constitutively to the economic, with which, in the form of commissions and land values, it has a virtually unmediated relationship… Yet this is the point at which we must remind the reader of the obvious, namely that this whole global, yet American, postmodern culture is the internal and superstructural expression of a whole new wave of American military and economic domination throughout the world: in this sense, as throughout class history, the underside of culture is blood, torture, death and horror.

– Fredric Jameson, “Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism” (1984)

I visited Los Angeles for the first time in the winter of 2017. There were plenty of places I wanted to see — The Museum of Jurassic Technology, Griffith Observatory, In-N-Out Burger — but the attraction that most fascinated me was the Westin Bonaventure Hotel in Downtown Los Angeles, a mirrored fortresslike structure designed by John Portman that I had read about in Fredric Jameson’s landmark 1984 essay “Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism.” I was reminded of the essay again this fall after learning of Professor Jameson’s death at age 90.

Jameson’s “Postmodernism” essay had been assigned to me in college as part of a memorable seminar course that focused on critical theory and architecture. The name of the course escapes me now, but not the professor, a native of Los Angeles who conveyed her ideas about architecture, urban planning and consumerism by means of lively anecdotes about a childhood spent against the backdrop of gated communities, superhighways and wildfires.

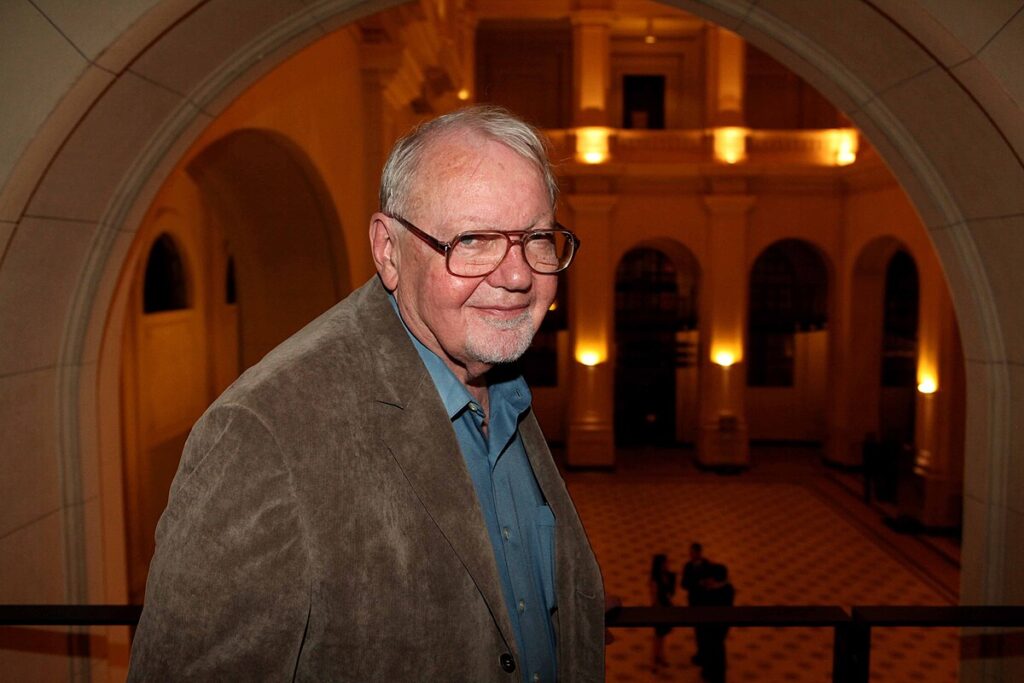

Fredric Jameson (1934-2024) was one of the world’s leading academic critics. Working in the traditions of Marxism and critical theory, Jameson wrote on a wide range of topics, from literature to contemporary art, but he had an especially profound influence on the theorization of architecture. Fronteiras do Pensamento, Fredric Jameson na Sala São Paulo (5768677304), CC BY-SA 2.0

Since then, my sense of Jameson has been mixed up with the idea of Los Angeles. Or rather, with a particular idea of Los Angeles: a gothic one that I first became familiar with through films. In classics like Chinatown and Mulholland Drive, Los Angeles is portrayed as a cursed place, a city founded on an originary crime or sin. In such films, it is impossible not to read Los Angeles as a metaphor for the American empire and capitalist modernity more broadly.

Jameson would never have described the symbolism of Los Angeles as crudely as I just did, but his famous analysis of the Bonaventure Hotel suggested that he saw the city this way too — as a place that is defined by its ghosts. Indeed, it was admirers of Jameson, especially Mark Fisher, who developed the now popular tendency of Gothic Marxism, the view that there is something spooky or spectral about capitalism, an economic system that runs on dead labor. (Jon Greenaway’s recent book Capitalism: A Horror Story is a great primer to this way of thinking, as is Fisher’s The Weird and the Eerie.)

The horror of the Bonaventure Hotel, Jameson wrote in his famous “Postmodernism” essay, is a horror of incomprehensibility. While many are familiar with the idea of postmodern buildings containing stylistic “references” that don’t, together, add up to a coherent system, the crisis of meaning reflected in the Bonaventure has more to do with its confusing floorplan and awkward relationship to the surrounding neighborhood.

This latter point is key, as for Jameson the essential feature of the Bonaventure is its rejection of the outside, its attempt to function as a total world in itself, a mini city where people can shop, congregate, and gaze at one another across looping skywalks and mezzanines. The fact that it is Downtown LA outside, and not Cleveland or Singapore, is more or less incidental, and Jameson reads a lot into the fact that the front entrance to this hotel is hard to find. He speculates that Portman might have viewed the need for doors almost as an embarrassment, “for [the hotel] does not wish to be a part of the city, but rather its equivalent and its replacement or substitute.”

Jameson continues: “But this disjunction from the surrounding city is very different from that of the great monuments of the International Style: there, the act of disjunction was violent, visible, and had a very real symbolic significance — as in Le Corbusier’s great pilotis whose gesture radically separates the new Utopian space of the modern from the degraded and fallen city fabric which it thereby explicitly repudiates (although the gamble of the modern was that this new Utopian space, in the virulence of its Novum, would fan out and transform that eventually by the very power of its new spatial language). The Bonaventura, however, is content to ‘let the fallen city fabric continue to be in its being’ (to parody Heidegger); no further effects, no larger proto-political Utopian transformation, is either expected or desired.”

So the Bonaventure aspires to be a world unto itself, but not an image of a new world. It is a space for escapism, entertainment, a floating fragment that refuses to be defined by its context, either by attempting to relate to it or by rejecting it outright as the modernists had done. On the top level, there is a rotating bar where one can gaze out at the city from a safe distance.

Exterior view of the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, CC BY 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

For Jameson, the Bonaventure represents the crisis of capitalism in the late 20th century, a period he describes as “late capitalism” but which has also been called neo-liberalism or post-Fordism. The idea is that this is an era when the global system is experienced as vast and overwhelming to subjects in developed countries, especially workers, who are less capable than in previous periods of grasping their class position by participating in organizations like labor unions. Politics becomes harder even to theorize as faceless corporations assume more and more power over everyday life. (Think Ned Beatty’s famous speech in Network). In this environment, culture increasingly turns toward solipsism and spectacle.

To me this all sounds very “LA,” dystopian but also glamorous, like looking at your own reflection in the mirrored sunglasses of an indifferent celebrity. Jameson was a midwesterner who spent his academic career at Duke University in North Carolina, but for me he will always be the theorist of Southern California. As a lifelong denizen of the East Coast, I too only know Los Angeles as an outsider.

To summarize the breadth of Jameson’s work or his influence is beyond the scope of this article and frankly my abilities. My brush with his writing was only a little more than casual. But it would not be an exaggeration to say that it changed me. After reading him, I never again saw architecture as anything other than deeply tied to politics, and especially the political unconscious. Buildings are additions to cities intended to last for many years. Whatever architects think they are doing, they are, in a very real sense, designing proposals for the future. And thinking about buildings this way can yield insights on multiple levels.

I forget what drink I ordered when I visited the rotating bar at the top of the Bonaventure Hotel. I do remember thinking that this building, which seemed hyper-contemporary to Jameson in 1984, had come to seem, in 2017, comfortably retrofuturist. Perhaps in trying to create a complete and sealed environment, Portman had attempted to exorcise the ghosts of the past, the stain of the surrounding city. But now, unmistakably, there were ghosts here too.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Cover Image: Detail of the Westin Bonaventure. Photo by Joe Howell, CC 2.0 via Pexel.