Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.

Brutalist architecture provokes strong reactions. It challenges traditional standards of architectural value with its unique character, emphasizing raw concrete surfaces, imposing scale and bold forms. Some see it as a celebration of material, form and function; others perceive it as cold and uninviting. Brutalist architecture hardly goes unnoticed, prompting us to reevaluate how we see and use spaces, ultimately enriching the human experience and leaving a lasting impact.

Brutalism emerged primarily in the late 1940s and gained prominence in the 1950s—1970s. It is known for its bold forms and unapologetic use of raw materials, particularly exposed concrete. Emerging after World War II, Brutalism reflects a desire for honesty in design, emphasizing functionality over ornamentation. The design approach strips buildings to their structural essence, making materials and construction techniques integral elements of the aesthetic. Brutalist buildings often appear monumental and imposing, evoking a sense of strength and permanence in a time of societal rebuilding and modernization post-World War II.

Characteristics of Brutalist Architecture

Boston City Hall Public Spaces Renovation by Utile, Inc., Boston, Massachusetts | Designed by Kallmann McKinnell & Knowles and Campbell, Aldrich & Nulty 1962-1968

How is Brutalism associated with Modernism?

Brutalism is closely associated with Modernism, as both movements focus on functionality and honesty in materials. As a post-war evolution of Modernism, Brutalism maintains its predecessor’s rejection of ornamentation, favoring structural clarity. However, Brutalism differs from Modernism in its aesthetic and material choices. While Modernism often features sleek, minimalist forms with extensive use of glass and steel — as exemplified by the Seagram Building in New York City — Brutalism predominantly embraces raw concrete, resulting in more rugged structures. Modernist constructions, such as the Seagram Building, typically aim for lightness and openness, whereas Brutalist architecture evokes a sense of massiveness and permanence. Despite these differences, both styles promote an architecture that reflects societal needs and values, focusing on functionality and breaking away from historical revival styles.

History of Brutalist Architecture

Seagram Building (1958), designed by Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson. New York, New York | (Ken OHYAMA, Seagram Building (35098307116), CC BY-SA 2.0)

What architectural movements preceded Brutalism and contributed to its development?

The influences of Brutalism are diverse and multifaceted. Modernism, particularly the International Style with its emphasis on functionalism and minimal ornamentation, significantly influenced Brutalism. Le Corbusier’s béton brut (raw concrete) concept inspired Brutalism’s materiality. Bauhaus’s commitment to simple forms, honesty in materials, and the “form follows function” principle also played a foundational role. Also, the Arts and Crafts movement’s emphasis on material authenticity and craftsmanship contributed to Brutalism’s raw aesthetic, despite their differing scales and approaches.

What events led to the decline of Brutalist architecture?

The decline of Brutalist architecture was driven by several factors. A growing public perception of Brutalism as cold, oppressive, and alienating led to widespread criticism. As urban renewal projects progressed, many Brutalist buildings were associated with social issues like crime and decay, especially in neglected public housing projects. A shift toward more visually inviting, postmodern, and neo-vernacular styles in the 1980s and 1990s also played a role, as architects embraced ornamentation and human-scaled forms. Additionally, the economic challenges of maintaining large concrete structures contributed to the decline, as many Brutalist buildings suffered from wear and corrosion over time.

Examples / Case Studies

Who are the key architects credited with pioneering Brutalism and how did the style adapt regionally?

Regional variation adapted Brutalism’s raw, honest aesthetic to meet specific cultural, climatic, and functional needs.

- Europe:

In the United Kingdom and Eastern Bloc countries, Brutalist architecture was typically used for public housing and government buildings. This architecture embodied social progress and functionality ideals, addressing post-war rebuilding efforts. In the United Kingdom, Alison and Peter Smithson led the movement with projects like the Robin Hood Gardens housing development (1972). In Eastern Europe, Karel Prager (Czech Republic) contributed significantly to the movement with projects like the Prague Assembly Building (1966-1974), adapting Brutalism for government and housing projects.

- Soviet Union:

Erich Mendelsohn, Leonid Pavlov, and Arkady Mordvinov were associated with Soviet Brutalism, creating massive, imposing buildings that reflected state power.

- United States:

Brutalism was embraced for institutional buildings, universities, and urban redevelopment projects, emphasizing monumental forms and functionality. Notable examples include Paul Rudolph’s Yale Art and Architecture Building (1963) and Marcel Breuer’s Whitney Museum of American Art (1966). - South America:

Brutalism emerged in South America as an important architectural style. In Brazil, Lina Bo Bardi’s Museu de Art São Paulo (1968) and, most notably, Oscar Niemeyer’s sculptural buildings, such as the Cathedral of Brazilia (1970) blended the style with regional architectural traditions and environmental considerations. Similarly, Clorindo Testa in Argentina led the movement, integrating Brutalist principles with local adaptations.

- Tropical Climates:

Brutalist designs in tropical regions adapted to the climate by incorporating lighter materials and passive cooling strategies. Examples include the works of architects like Le Corbusier in Chandigarh, India.

The Future of Brutalist Architecture

Palace of Assembly (1951), designed by Le Corbusier. Capitol Complex of Chandigarh, India. | (UnpetitproleX, Palace of Assembly Chandigarh, CC BY-SA 4.0)

How has public opinion on Brutalism evolved?

In its early years, the style was celebrated for its boldness and revolutionary approach to architecture, especially in post-war rebuilding efforts. However, as the decades passed, Brutalism’s massive raw concrete forms, for some viewed as cold and unwelcoming, began to be associated with urban decay, leading to calls for demolition.

More recently, Brutalism has experienced a resurgence, fueled by a nostalgic appreciation for its boldness and an interest in architectural heritage preservation. Brutalism is now seen as a reflection of the post-war social and cultural climate, sparking debates on its architectural value and integration into contemporary urban landscapes.

The style’s cultural relevance is evident with a strong presence on social media platforms like Instagram, where accounts like @swiss_brutalism, @brutalism101, @brutalismo_esp, @brutalist_design, @african_brutalism, and @b_r_u_t_a_l_i_z_m demonstrate its enduring popularity in contemporary discourse.

Does Brutalism align with or contradict contemporary sustainability practices?

Brutalism intersects with contemporary sustainability practices in two contrasting ways. On the one hand, its use of raw concrete, a durable and low-maintenance material, aligns with sustainable urban planning principles. Brutalist structures, designed for endurance, require less frequent demolition or rebuilding, which reduces long-term resource consumption.

On the other hand, concrete production has a high carbon footprint and is associated with greenhouse gas emissions, presenting an important environmental challenge. Also, many Brutalist buildings struggle with thermal efficiency, further complicating their sustainability.

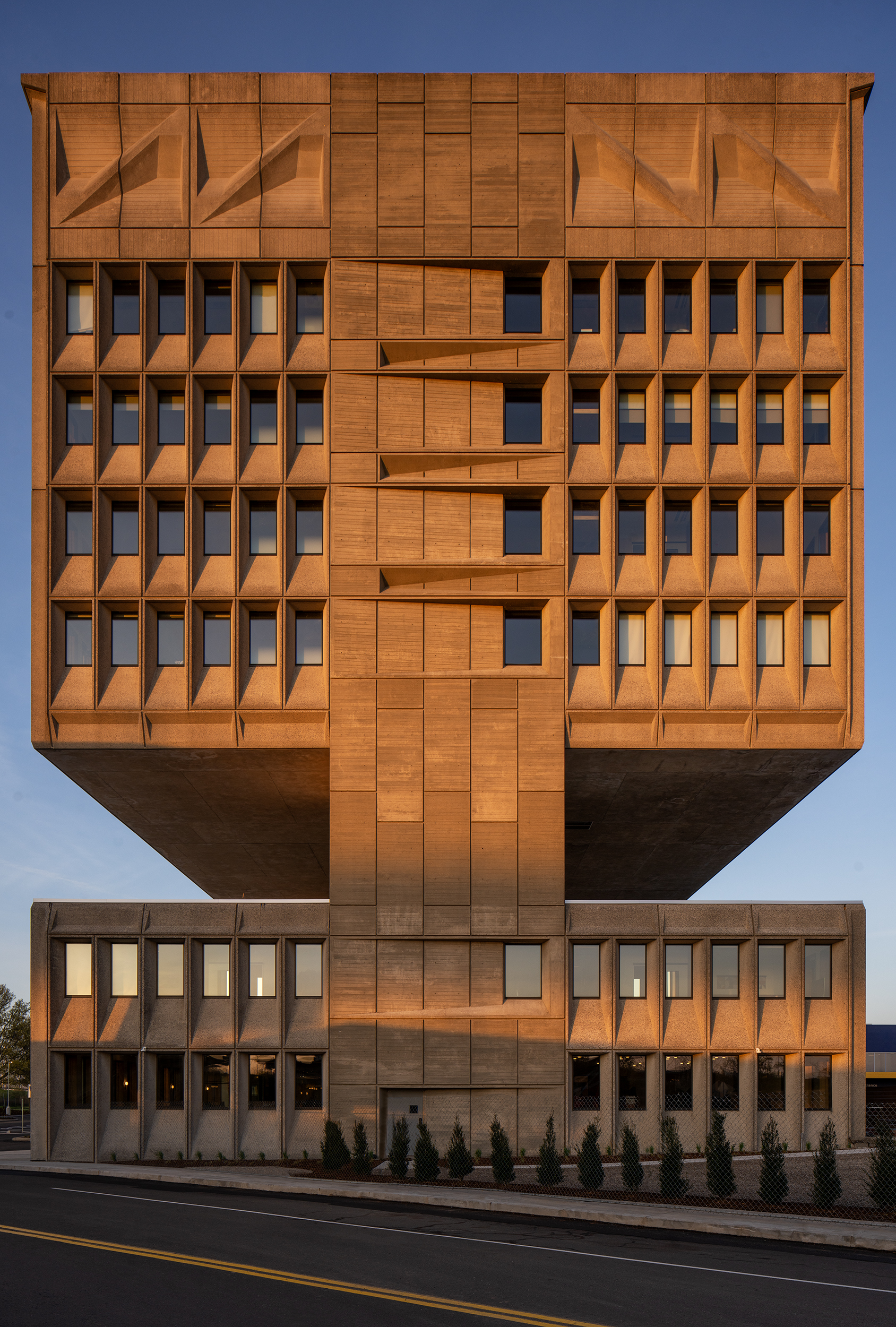

Hotel Marcel by Becker + Becker, New Haven, Connecticut | Designed by Marcel Breuer in 1968

How is Brutalism being adapted today and what is the state of conservation efforts?

Today, Brutalism is being reinterpreted in various ways, influencing modern architectural aesthetics and conservation practices. Drawn by Brutalism’s raw, unpolished look, many contemporary architects incorporate raw concrete and exposed structural elements into their designs while blending Brutalist principles with more modern materials and techniques to create buildings that feel more inviting and integrated into their surroundings.

As cities and communities recognize their historical and architectural significance, preservation efforts for Brutalist buildings are increasing. Notable examples include Habitat 67 in Montreal, Canada; the Barbican Estate and Trellick Tower in London, United Kingdom; Boston City Hall in the United States; and the Sirius Building in Sydney, Australia. These projects highlight a growing appreciation for Brutalist architecture as part of our cultural heritage. While some Brutalist buildings face demolition due to neglect, many are being upgraded for modern use while maintaining their distinct raw character. Architects and urban planners can explore how these structures can be reinterpreted to meet contemporary needs by preserving and retrofitting Brutalist buildings, thus bridging their past with a sustainable, inclusive future. A notable example is Marcel Breuer’s Armstrong Rubber Company Building in New Haven, Connecticut, United States, now the Hotel Marcel. After decades of disuse, the building was transformed into the first Passive House-certified hotel in the United States, blending Breuer’s original vision with cutting-edge sustainability.

How has Brutalism influenced architectural thinking and society at large?

Today, Brutalism encourages the rethinking of architectural values, with an interest in preserving its iconic structures and adapting its principles for a contemporary lifestyle. Its legacy is a testament to architecture’s ability to provoke thought, shape identity, and respond to societal challenges.

Brutalism teaches us that architecture is not just about aesthetic trends. It is a tool for reflecting societal values. Brutalism’s raw materiality, imposing forms, and utilitarian emphasis reflect the post-war need for affordable housing, public infrastructure, and social equity. However, Brutalism also provokes debate by forcing us to question what we value in the built environment and who benefits from it. In this way, Brutalism remains a reminder that architecture is not neutral but a reflection of cultural, political, and economic values.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work by uploading projects to Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletters.