Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.

“Yes, and…” thinking has long been a guiding principle in Improv comedy. The suggestion that improvisors should accept the premise of the preceding sketch (“yes”) and then expand upon it (“and”) has, in recent years, become shorthand for expansive thinking that actively avoids limiting ideas. For those who were not initiated in their high school drama class or brainstorming sessions, the term may be familiar from Amy Poehler’s 2014 memoir, “Yes Please.”

When Laura Starr, Principal at the New York-based landscape firm, Starr Whitehouse, first came across the “Yes, and…” concept, it resonated — and for good reason. From March to May of 2021, her team led the community engagement for the redesign of a notable state park in Brooklyn that consisted of an outreach approach of “saying yes to everything.”

In many countries around the world, appreciation of parks may be at an all time high. A year of social distancing has not only created a new appreciation for outdoor public space but has also sharpened public opinion around just how these spaces can better serve community needs. This coincides with a spike in distrust of top-down planning due to recent controversies such as East River Park, the Sunset Park rezoning, and the Amazon Long Island City deal. Even more recently, this was seen in the Stop the Plastic Park movement, which emerged in Brooklyn in response to the proposed redesign of what was formerly known as East River State Park in Williamsburg, undertaken to reflect the state’s historic decision to rededicate the park to Marsha P. Johnson, a prominent LGBTQ+ advocate and forebear of the transgender rights movement.

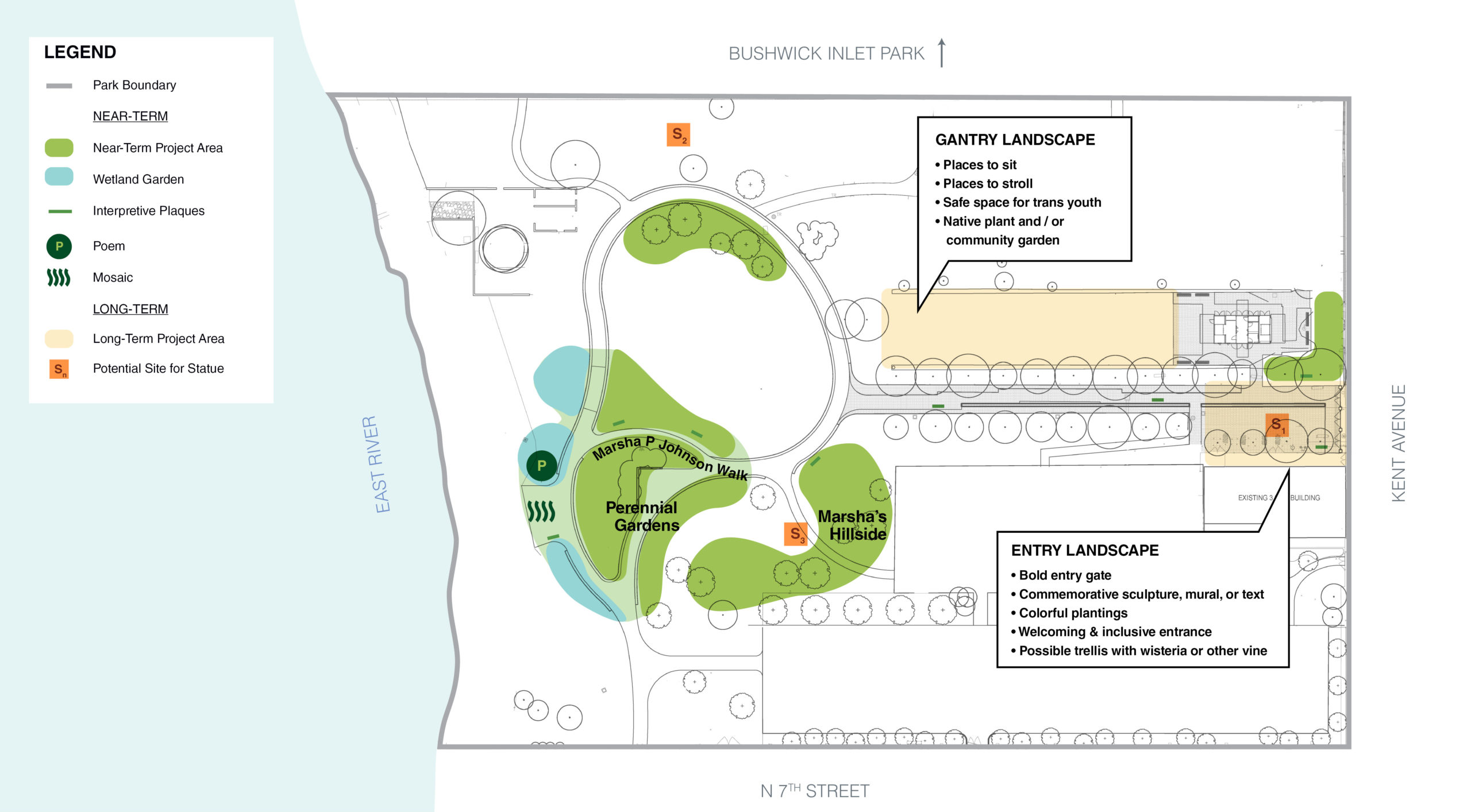

The final Redesign for Marsha B Johnson Park was the result of a month-long community engagement and public design workshop process lead by Starr Whitehouse.

The backlash was not against the rededication itself but rather was focused on the addition of a large thermoplastic mural celebrating the namesake. The material controversy became a microcosm of the sentiment that the community was not adequately consulted in the design process. In response, NYS Parks hired Starr Whitehouse to lead an inclusive public design process in order to balance the respectful commemoration of Johnson’s esteemed legacy while also fulfilling local resident’s longstanding dream for an open waterfront green space.

The challenge of building consensus around a single shared vision in any public project is complex and this particular case had its own unique challenges. The community involved was not simply limited to residents of the surrounding area (as seen in surveys returned from zip codes all over Manhattan): advocates, state officials, Smorgasburg vendors, Johnson’s family, and transgender leaders of color all have visions and personal connections to the space. As Michael Haggerty, Senior Associate at Starr Whitehouse added, even within these groups, opinions were not monolithic and individuals’ desired outcomes were diverse.

Indeed, when people think about public space, they still tend to think about how they, as individuals, would use the space. Yet, parks are public resources and space that needs to be shared. As Starr Whitehouse’s success demonstrates, one of the landscape architect’s roles in community-led design is to orchestrate these individual desires and to figure out how they can work together to make the space engaging and exciting in a way that pleases everyone. In order to do so, their process combined a series of online panels (in Zoom format) and on-the-ground outreach in the park itself (tabling), in order to prioritize inclusivity. Leslie Wright, head of parks of the New York City region for the state parks, and other staff from the department remained heavily involved in the 48 hours of outreach that took place over the month of April and early days of May.

Images courtesy of Starr Whitehouse

This dual-approach was crucial to the project’s ultimate success. One the one hand, listening to online sessions, where community members presented their ideas, enabled the various groups to hear each other out and, therefore, to expand upon one another’s ideas. On the other, the advantage of outdoor outreach in the park itself allowed the architects to engage community members and park users who wouldn’t have otherwise been involved in the process.

Starr says that the keywords that lead to the success of the design were “listening” and “transparency.” This is physically manifested in a design process that was public and ongoing. In meetings and in the park, the architects would bring the current plans, often as a digital drawing on an I-pad, and then draw over top of them as community members expressed their ideas. This collaborative approach allowed them to look at the design and to think about it together as they explored new ideas and possibilities. Crucially, by illustrating the changes that were being made — that is, by keeping the drawings updated as the conversation progressed — the architects made clear what was happening and where the ideas were coming from.

Take for instance the idea of a commemorative walkway through the park, which was selected as an alternative to the unpopular thermoplastic mural that catalyzed the community engagement process. While Johnson’s family proposed the idea of colorful gardens that would celebrate the namesake’s life and personality, it was a member of the local community who suggested that the gardens become a walkway with commemorative panels to narrate key moments in her life. While the text pre-existed the redesign, there were only issues with their form and not their content. However, as the community was engaged and a more complex narrative of the park’s history came to light, it became clear that the story could be expanded to include a nod to the North Brooklyn community’s history of activism for the existence of the green space itself.

Images courtesy of Starr Whitehouse

Whether the space is new or already exists, the design and redevelopment of public parks also involves many stakeholders, making the outcome uncertain and the product of myriad collaborations. Even still, there is a general perception that community-led design is idealistic; that it looks good on paper but in reality slows the process down. Yet, the success of the month-long public design workshops for Marsha P. Johnson park demonstrate that it does not have to be so. Taking into account all of the changes included in the new design, the park is still set to re-open in the fall — just months after NYS Parks collaborated with Starr Whitehouse to undertake the community outreach.

As Starr explained, approaching public park design as a deliberate, incremental and community-led process allows the project to be implemented in a more direct and smooth way. All of this means that it may even cost less: rather than spending time, energy and resources backtracking to communicate reasoning behind top-down designs for public spaces, casting a wide net and allowing the public to feel more involved often leads to consensus, therefore saving clients and architects a lot of extra work.

A truly inclusive public process is premised on bringing together multiple constituencies who don’t necessarily agree on everything, and working to unit them around a common, tangible goal and shared vision. As Starr Whitehouse puts it: “The process was not easy, but in the end, it was a real victory for community voices shaping the public realm.” This author would add, Yes, and… it was also a victory for the architects and the client.

Architects: Want to have your project featured? Showcase your work through Architizer and sign up for our inspirational newsletter.