How is it that someone can live on nearly 60 years after their death?

Within the arts, that is actually a fairly probable fate if you’ve proven yourself to create enduring pieces of work that channel genuine inner self-expression. Of course, it is not like most of us live our lives assuming our work will last forever, but the one medium that often trumps others in terms of staying power for both the art form and its creator is architecture. Truly great buildings are sewn into the earth and intrinsically influence how we perceive our environment. Visionary architects who manage to build even just one groundbreaking design have the potential to be remembered forever.

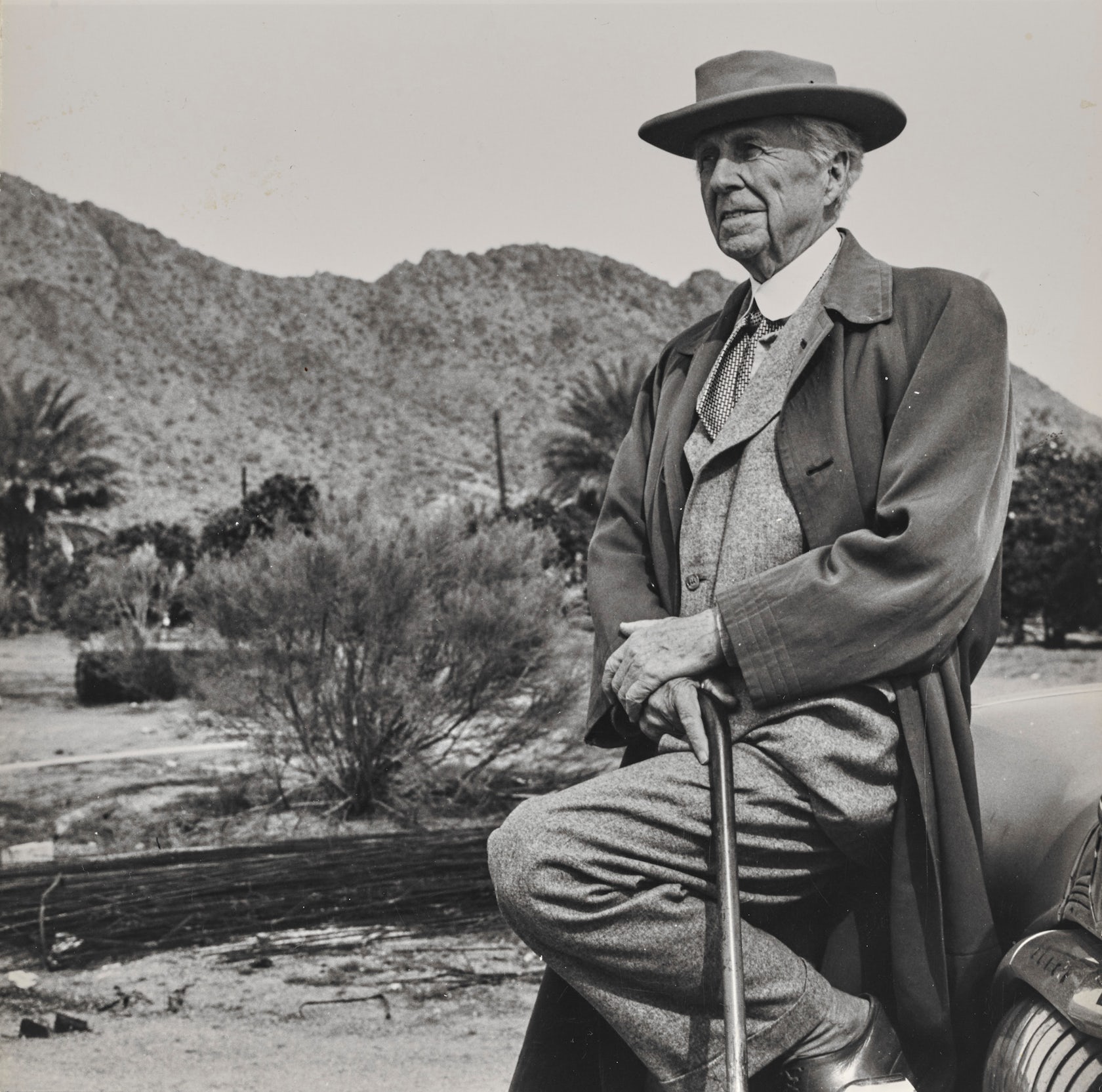

Despite the enormous rarity of this, one architect actually did live his life with a personal mission of becoming a “godfather in the profession”: Frank Lloyd Wright. Considered by many to be the most important American architect of the 20th century, his faith in himself and his sheer talent made him into an undeniably legendary figure. On the 150th anniversary of his birth, we’re taking a look at what made him so relevant and what keeps his legacy alive today.

Image courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Born in Wisconsin, Wright was taught to love architecture from an early age. His mother creatively adorned the walls of his nursery with engraved English cathedrals and later bought him the famous Froebel gifts building blocks to use during his kindergarten education. Those formative years spent piecing together the strict shapes of the blocks became the basis of the clear geometric language found throughout Wright’s architecture.

“There should be as many (styles) of houses as there are kinds (styles) of people and as many differentiations as there are different individuals. A man who has individuality has a right to its expression and his own environment.” — FLW

Some of his most memorable projects display this distinct detail in structure and shape. Though his architectural style — in the most rigid use of the term — developed over the years, Wright’s buildings are all quite recognizably Wright’s buildings. From the Prairie School Style of his early-20th-century residential designs like the historic Robie House in Hyde Park, Illinois, to the precast, textile concrete blocks he designed in California, Wright’s innovative architectural vision was always on the cusp of the latest design trend — if he hadn’t already started it himself.

Image courtesy the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (the Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Many of Wright’s most well-known projects — most notably Fallingwater, the iconic private residence at Mill Run, Pennsylvania — were conceived in the organic style as a nod to nature. Fallingwater was aptly constructed over a 30-foot waterfall, innately connecting the architecture with its natural surroundings.

“The good building is not one that hurts the landscape, but one which makes the landscape more beautiful than it was before the building was built.” — FLW

Taliesin West, the home of Wright’s signature architectural fellowship established in 1932, was also designed in response to the climate and bare landscape of Scottsdale, Arizona. Not only would Wright select materials that blended well into the environment, but the form and function of each facility he designed also directly related to its local context.

Wright essentially invented the early-to-midcentury Usonian style, a type of housing design that featured flat roofs, slab-on-grade foundations, sandwich walls and no basements or attics. These homes largely centered around the living spaces, encouraging families to spend time together in the largest areas of the house. This ideal set a new standard for suburban design in the United States.

Sixty Years of Living Architecture: The Work of Frank Lloyd Wright in New York. 1953. © 2017 Pedro E. Guerrero Archives; image courtesy the Museum of Modern Art; photo by Pedro E. Guerrero

Apart from Fallingwater, Wright’s most identifiable masterpiece is none other than the Guggenheim Museum. A project that took 16 years to complete, the building has been lauded for half a century as one of the most striking museums not only in New York, but in the world. The spiral structure and its descending interior ramp were inspired by Wright’s fixation with cars; he had quite the luxurious taste in clothes, furnishing and automobiles. While working on the world-famous contemporary art museum, he also managed to finish Price Tower in Bartlesville, Oklahoma, the sole skyscraper he ever designed and completed.

“I believe in God, only I spell it Nature.” — FLW

Almost as important as Wright’s physical built legacy is his intellectual influence. Wright was widely known as an outspoken critic of the profession. He refused to join the American Institute of Architects (AIA) on account of individualism. He was also something of a social rebel. Though his thoughts and actions were often deemed highly controversial and arrogant, Wright somehow managed to leave this world as a celebrated historical figure. He once told Mike Wallace in an interview that if he had 15 more years to work, he could change the nation.

It’s fair to think of Wright as the less rockstar-like, more jazzy predecessor of Bjarke Ingels. He made powerful projects, had a powerful voice and was recognized worldwide — both as a man and an architect. And while he’s still quotable to this day, it’s Wright’s 532 built projects that will stand the test of time, allowing his legacy to carry on from 150 years of influence to 200 years and beyond.

“Architecture is life, or at least it is life itself taking form and therefore it is the truest record of life as it was lived in the world yesterday, as it is lived today or ever will be lived.” — FLW

Happy birthday, Frank Lloyd Wright!