Design for accessibility is practiced widely in architecture but there’s a growing consensus the profession is doing it backwards. Universal Design, an approach to space-making that ensures any person of any ability can use any space, has been gaining steam in recent years. Rather than designing just to accessibility codes, which often creates segregated spaces for people with different levels of ability, Universal Design is based on the simple concept of designing for people in a comprehensively inclusive manner.

In an effort to embed Universal Design in architectural education, Ascension Wheelchair Lifts recently teamed up with the University of Arizona’s College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture to create a semester-long design studio and awards program focused on Universal Design. “As we engage in discussion about diversity, equity and inclusion, we often neglect to include our ableist biases in the conversation,” said Teresa Rosano, Assistant Professor of Practice in Architecture, who led the studio.

“The goal of the program is to help bring Universal Design principles to the forefront of the design process and ensure that future spaces are more welcoming and accessible for everyone,” said Howard Stewart, Ascension’s CEO and President.

To address this shortcoming, students in the class were tasked with designing a building on a steeply sloped site, which posed a challenge to implementing Universal Design principles by making it impossible to place the building’s entire program on a single floor. Forced to recognize the difficulties people with various levels of ability face when using buildings designed only to meet accessibility codes, students reconciled concerns ranging from vertical circulation and safety features to signage, wayfinding and sensory stimuli. Here’s a look at the winners.

“Emerge” by Jules Cervantes

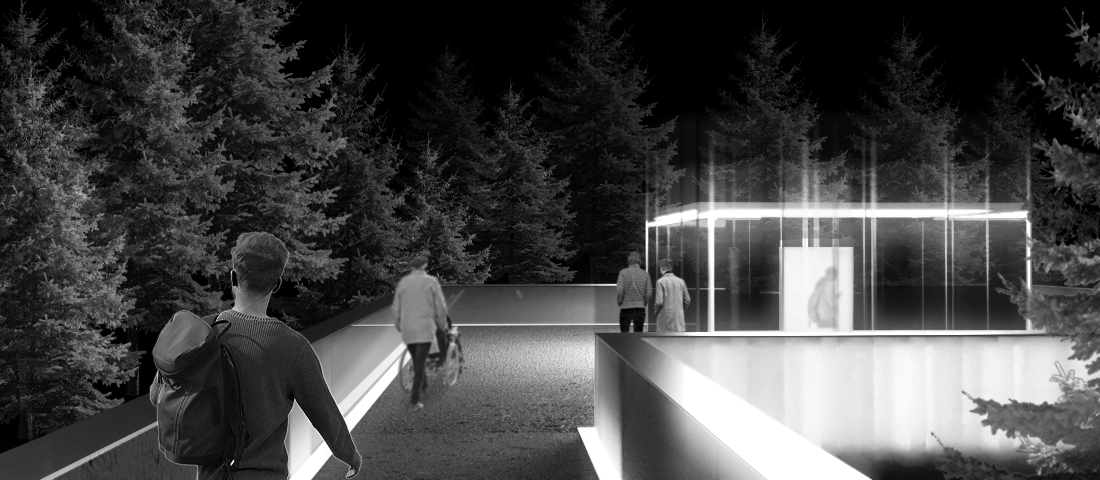

Jules Cervantes snagged the studio’s top Honor Award by minimizing complexity. “The simplicity in daily use can sometimes be overlooked in architecture,” she said, “but by designing with the user in mind, architects can create experiences that serve a diverse range of needs, resulting in more inclusive and intuitive designs.”

The concept of simplicity is evident in every aspect of her design, which takes the shape of a single form extruded from the ground up. Connected to the adjacent hillside on an upper level, the entry floor cantilevers among the surrounding trees on the opposite side “to serve as a reminder of the trees that surround it, both grounded and rooted but still reaching up and out,” she said.

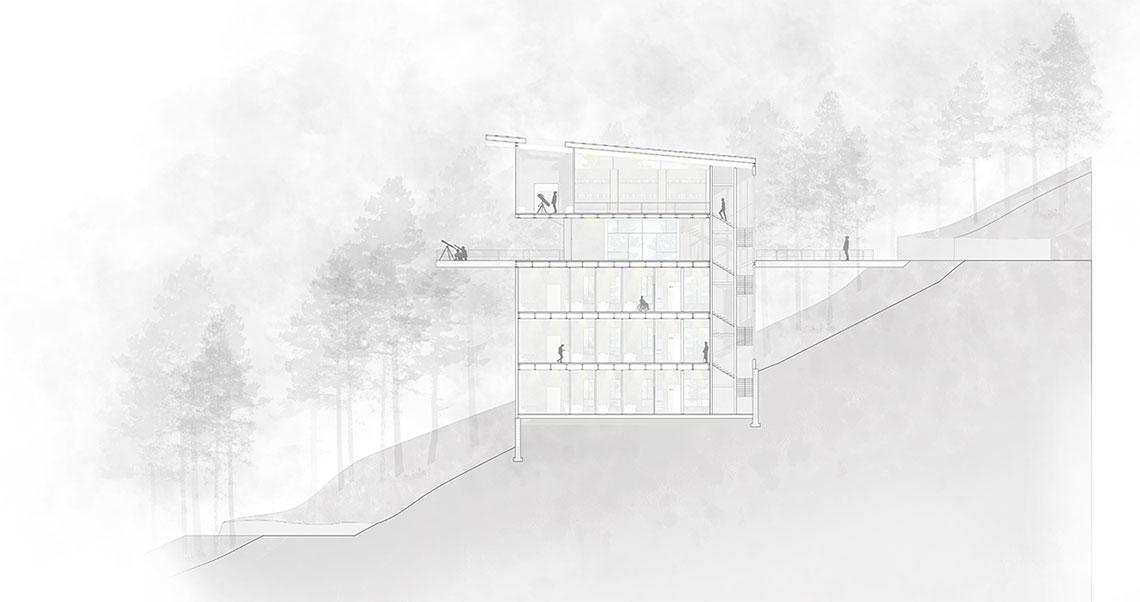

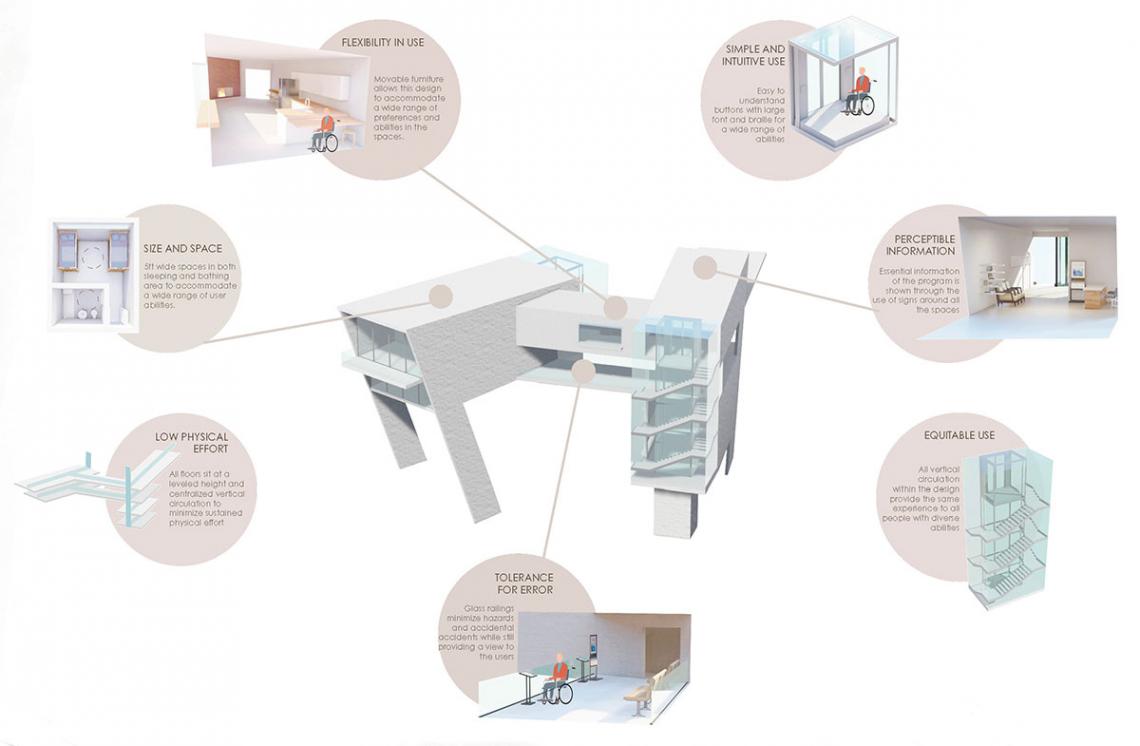

“Mount Lemmon Science Learning Center” by Hunter Jinbo

Winning a runner-up Merit Award, Hunter Jinbo’s Mount Lemmon Science Learning Center recognizes the importance of empathy in Universal Design. “Instead of imagining the flow of how I would walk through the structures I imagined the flow of someone with disabilities,” she said.

Her project clearly illustrates that Universal Design is best implemented in a building’s details. By specifying glass railings as opposed to opaque ones, wheelchair users are afforded the same perspective as anyone else. Co-locating stairs and elevators, and wrapping both with glass to give them the same view, exemplifies the notion of designing for equal enjoyment by all users, in addition to equal access.

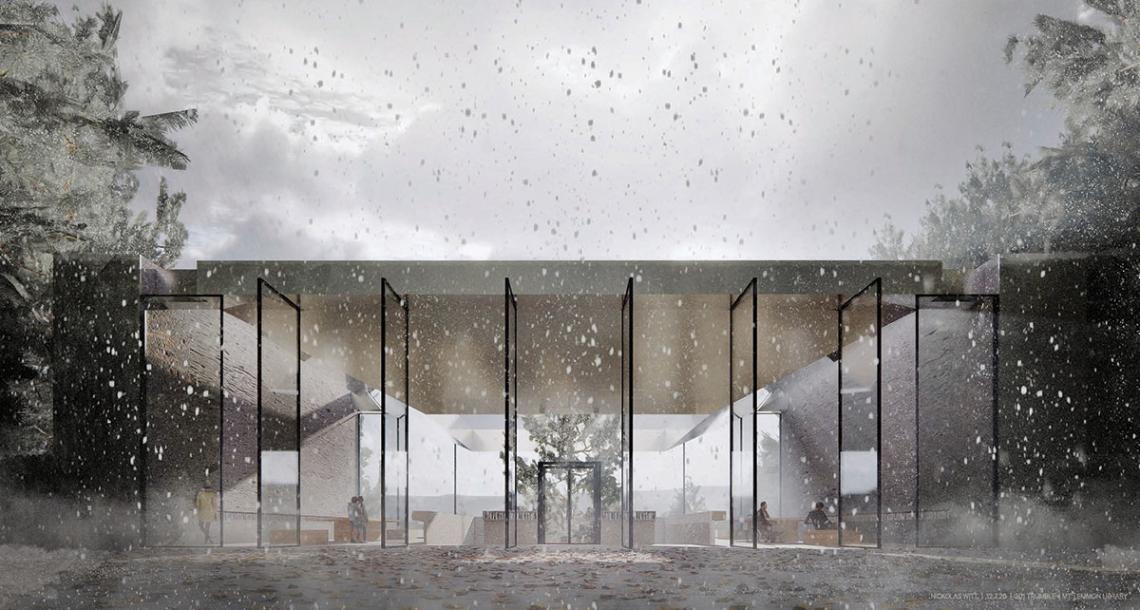

“Mount Lemmon Outdoor Library” by Nikolas Witt

Given a second Merit Award, Nickolas Witt found guidance in “the ability to understand and prioritize universal design at the beginning of the creative process.” His thoroughly crafted design is realized in an elegant, compact structure that consolidates a mix of indoor and outdoor space on only two levels.

Carefully-considered details in Witt’s “Mount Lemmon Outdoor Library” include free-standing furniture with no obstructions underneath, while other pieces, such as beds and bookcases, are integrated within the building’s walls, cutting down on obstacles. All the doors in the building either slide or pivot, reducing or eliminating thresholds for ease of access by wheelchair users.

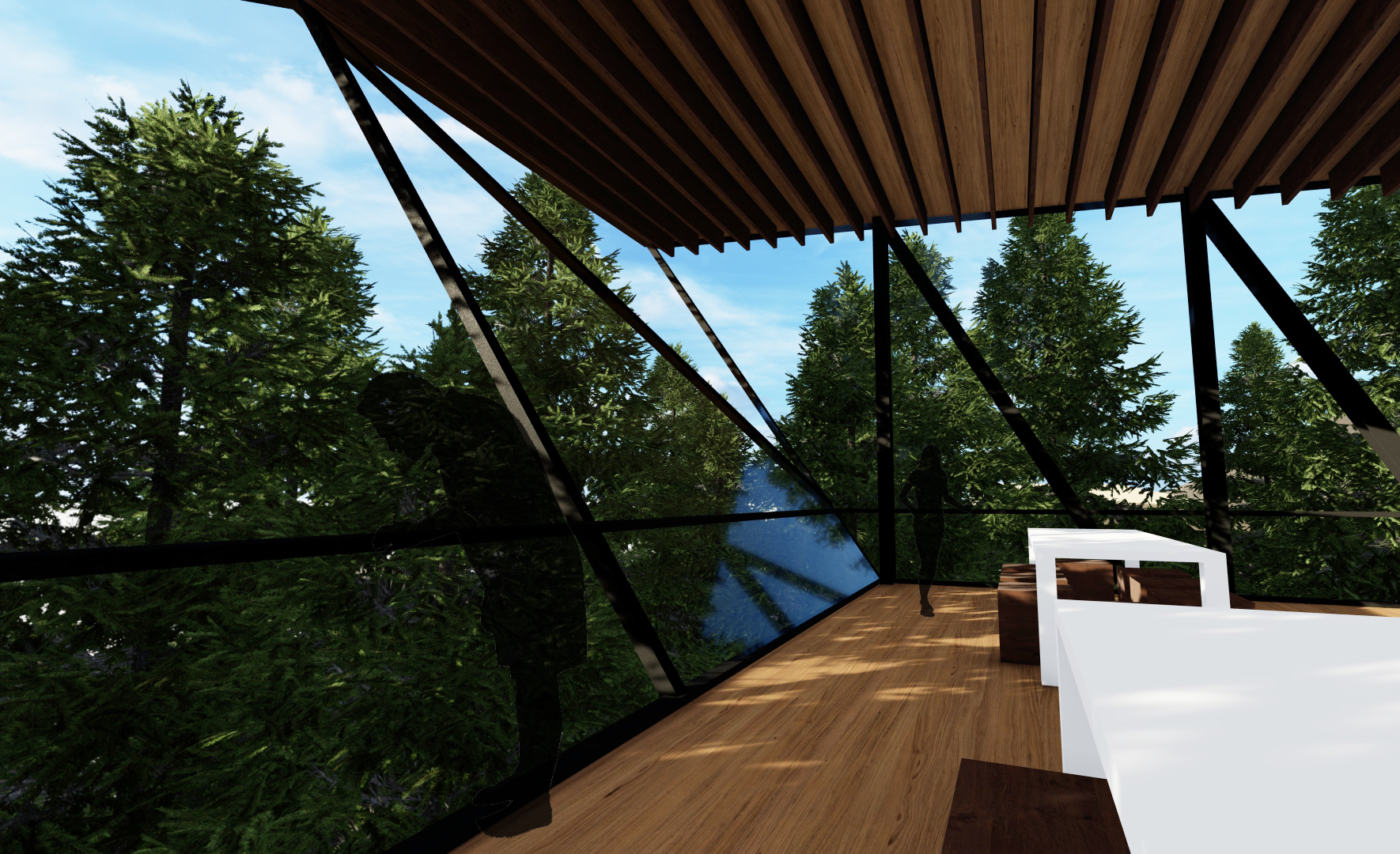

“For a Better Future” by Kaya Orona

“I used a wheelchair for two years due to a chronic illness, so aspects of universal design are always on my mind,” Kaya Orona, winner of an Innovation Award, said. Situated high up among surrounding treetops, an appreciation of nature is enhanced through her design with elements intended for enjoyment by users of any ability, such as floor-to-ceiling glass and low-profile handrails.

“Mt. Lemmon Culinary Camp” by Jack McCahon

Winning another Innovation Award, Jack McCahon’s “Mt. Lemmon Culinary Camp” employs the site’s slope to the advantage of Universal Design by creating entries on multiple floors. Choosing to organize the building as a cubical grid structure with generous dimensions, McCahon was also able to create especially wide hallways and bathroom spaces, accommodating useful features such as large, movable furniture.

“Science Learning Center” by Tiffany Valenzuela

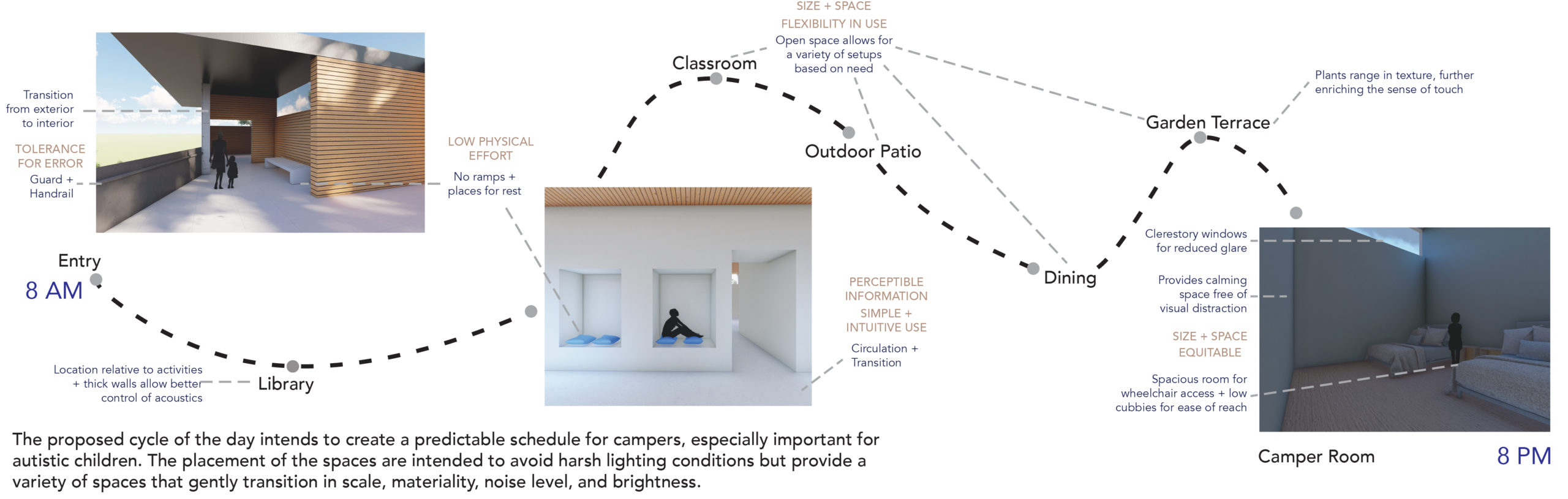

In addition to considering physical ability, Tiffany Valenzuela took on the added challenge of designing to facilitate education for children on the autism spectrum. To address this, her project features numerous details intended to convey particular sensory stimulations. Spaces are arranged in a sequence to emphasize a sense of structure in scheduled activities, while transitions between spaces are made intentionally gentle to avoid jarring sensations.

“Mediation” by Chris Kleha

Despite dividing the building onto three levels, Chris Kleha ensured a contemplative experience immersed in nature for all users by strategically puncturing offset floors, allowing existing trees to grow through outdoor courtyards. Featuring a faceted roof structure to divert rainwater, cavernous spaces directly underneath the roof offer stimulative meditation for occupants with any level of sensory ability.

“S.Sense” by David Zuniga

Also focusing on sensory stimulation, David Zuniga acknowledged that thinking beyond spatial dimensions is vital in implementing Universal Design. Looking to other disciplines outside of architecture for guidance, he drew on the works of multimedia artists such as Es Devlin and Olafur Eliasson to create a sensationally immersive environment, integrating lighting and auditory features to engage blind or deaf users.

To learn more about this inspiring competition and see how students from the University of Arizona are working towards the future of universal design, click here.