Architizer is building tech tools to help power your practice: Click here to sign up now. Are you a manufacturer looking to connect with architects? Click here.

What makes architecture radical? And, more importantly, is there ever a valiant reason to pursue radical design? A particularly powerful way to explore the answers to such questions is via the medium of architectural visualization, wherein a talented visual artist can conjure up hypothetical structures that would never be possible — or desirable — to create in the real world.

Havana-born architect, artist and graphic designer Adrian Labaut Hernández creates fictional architecture that explores contemporary issues within the urban environment, often subverting architectural theory to challenge the conventions of professional discourse.

Monumental Urbanism, New York, 1951

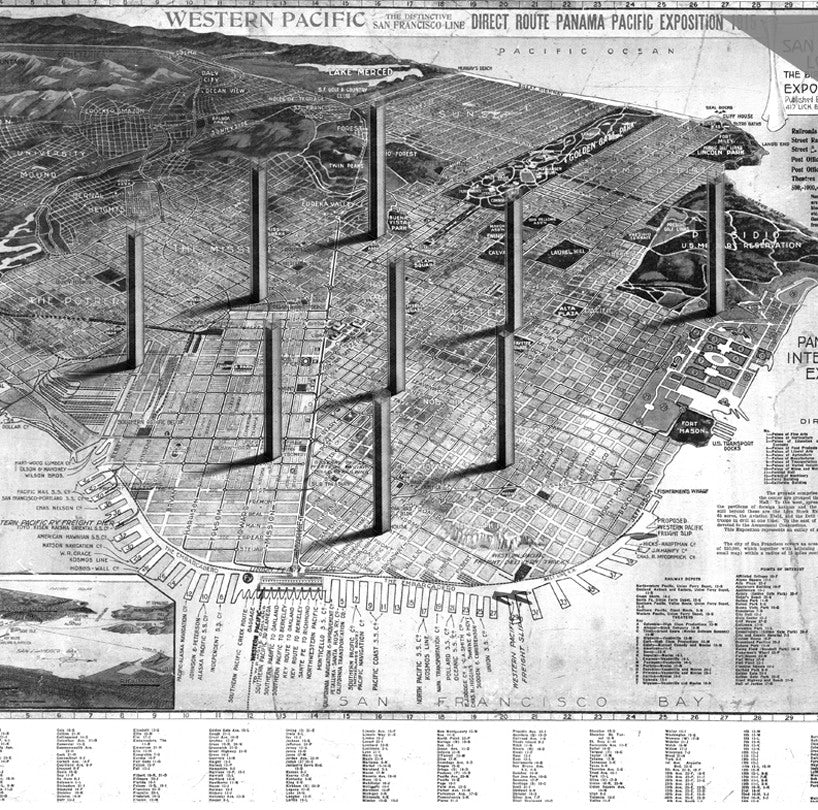

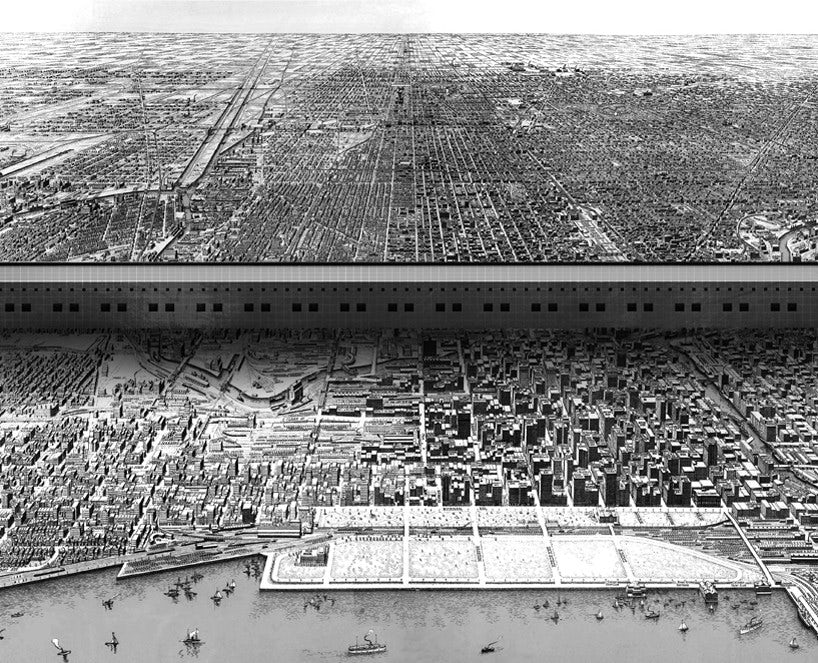

In one of his most recent series, titled “Manual for Becoming a Radical Architect,” Hernandez obliterated recognizable cityscapes with outlandishly large monuments, conjuring simultaneous feelings of awe and discomfort in the eyes of the viewer. These gargantuan forms dwarf the architecture surrounding them, displaying a willful disregard for humans at street level.

These architectural displays of radicalism come with appropriately ubiquitous names: “The Towers” reach skywards in San Francisco Bay, “The Cube” looms over the street grid of Philadelphia and “The Wall” dissects Chicago’s urban center. These provocative images bring to mind pertinent sociopolitical issues currently facing cities throughout the United States and across the world, stirring up notions of division, isolation and even oppression.

“The Towers,” San Francisco Bay, 1915

“The Cube,” Philadelphia, 1915

“The Wall,” Chicago, 1916

It could be argued that Hernandez is using scale to make a statement about architectural egotism prevalent throughout the last century, from the Monumentalism of Albert Speer’s master plan for Berlin to the pursuit of instant icons in modern-day cities such as Dubai. The artist’s renderings also echo ostentatious real-world proposals to overhaul swathes of urban fabric in cities like Paris — see Le Corbusier’s Ville Radieuse — and London, which might have been transformed into a Brutalist labyrinth of concrete edifices if developers had gotten their way in the 1960s.

While the images are capable of stirring up strong emotions, Hernández recognizes the folly of creating a radical object for its own sake. “Architecture does not need to say anything, it doesn’t need to talk, doesn’t need to express anything specific, and it doesn’t need, overall, to be needlessly ‘radical,’” explains the artist.

The Megastructure, Syracuse, N.Y., 1874

New Mobility System, Philadelphia, 1870

A Square Over New Orleans, La., 1885

He also emphasizes that, both practically and theoretically, it’s what’s inside that matters. “Architecture always has a meaning when it is created based on strong conceptual work, the project is there, a body of matter, showing itself immortal, personal, superior because of its inner qualities, those that can not be seen from outside and sometimes even from inside,” says Hernández.

“You need to look at it, speak with it, interact, explore, touch and at the end, for sure, admire. It is not done for a magazine page and neither to hang in an exposition room and amaze everybody around because it is ‘beautiful.’ Architecture justifies its own existence, it will emerge to create and show its own values, which at the end are completely rooted in life on this earth.”

While Hernández’ renderings should remain firmly lodged in the realms of fantasy, they are successful in their primary goal — to make us pause for thought, revealing how one of the most basic properties of architecture, scale, can fundamentally affect the human psyche.

Architizer is building tech tools to help power your practice: Click here to sign up now. Are you a manufacturer looking to connect with architects? Click here.

All images © AA; Labaut Architects via designboom